[Below is the full and slightly extended text of my Sunday Times article awkwardly titled “While the rich get education, SA’s poor get just ‘schooling’” [8/11/2015]

Looking back on the last 30 days in South Africa you cannot help but conclude that the issue of university exclusion on financial grounds has struck a nerve in the national psyche. There are not many issues in our country where there is universal consensus across issues of race or class, and yet this is one of them.

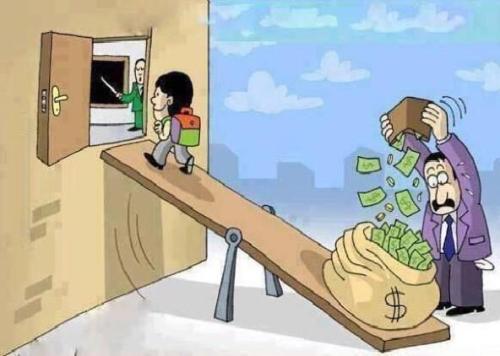

Deserving students should not be excluded from university because their parents cannot afford the fees. This is unjust, unsustainable and unacceptable as almost everyone now agrees. How we will pay for this is another story – and one that deserves attention – but we all agree that rationing access to limited university positions cannot be based primarily on parental income. Yet, this is exactly what happens in South African schools.

If you can afford to send your child to a former Model-C school or a private school, there is no question about it, you do! I am willing to bet (and AfricaCheck please follow up on this) that there is not a single member of Parliament who sends their child to a no-fee school in our country. Not one. It is an unspoken truth that no-fee schools are for the poor and ‘good’ schools are for the rich. To put this in context, no-fee schools make up the vast majority ranging from 66% to 88%* of schools (depending on if you ask students or principals respectively), and almost all of them are dysfunctional in that they do not impart to students the necessary knowledge, skills and values needed to succeed in life. There are at least 10 different independently conducted nationally-representative surveys attesting to this.

The problem here is two-fold: (1) Most parents cannot afford the fees at these schools since they are frequently as high as university fees (R31,500 per year), and (2) there are very limited places in these schools. Of the 25,741 schools in South Africa only 1,135 are former Model-C schools and 1,681 are independent (private) schools. Put together that accounts for only 11% of total schools. Even if we abolished fees in all these schools – and I’m not sure that is the way to go – you cannot fit 12 million children into 2,816 schools!

I completely agree that a system where access to quality schooling is almost exclusively a function of parental wealth (i.e. our current system) is unjust and must change. But purely from a numbers perspective we simply have to find ways of improving the quality of the 88% of schools that are already no-fee. Thinking about South African schooling as a zero-sum game where there is fixed number of ‘good’ schools will not get us very far.

Why do we have fees?

The reason why we have public schools that charge fees is that policy-makers at the time of the transition were afraid (probably correctly) that if they abolished fees in public schools, all white teachers and white students would go to private schools and we would be stuck with mostly white private schools and exclusively black public schools. Allowing these former white-only schools to charge fees was the trade-off for preventing that outcome. To try and prevent a system that was split entirely on ability to pay, the Constitution declares that no child can be denied admission to a school because his/her parents cannot pay fees.

Yet this is exactly what happens in the majority of cases. How is it that the majority of fee-charging schools manage to maintain a student body drawn primarily from that small subset of the population that can pay fees? Presumably by excluding the ones that can’t pay fees, in formal and informal ways. After speaking to some of the principals of these schools – many of whom are incredibly dedicated and committed to social transformation, I am not under any illusion that there is a simple answer to this or that these are not well-meaning individuals who are trying to maintain a high-quality of education on a very tight budget. Yet the reality remains – . The rich get access to universities and well-paying jobs while the poor get menial jobs, intermittent work or long-term unemployment.

According to the Quarterly Labour-Force Survey of 2014 the South African labour market can be split into four groups with the proportion of the working age population in each group included in brackets:

- Unemployed (broad definition, 35%),

- Unskilled (domestic workers and elementary occupations; 18%)

- Semi-skilled (Clerks, service-workers, shop personnel etc.; 32%)

- Highly-skilled (Legislators, managers, associated professionals; 15%)

The tragic reality in South Africa is that if your parents are in the ‘top’ part of the labour market (the 15%) then you send your children to the ‘top’ part of the schooling system (which charges fees). That gives your children access to university and to that same ‘top’ part of the labour market that you are currently in. If you are in the ‘bottom’ part of the labour-market (the 85%) then the only schools that you can afford and that are available are the second-tier no-fee schools. However, these schools are of an extremely low quality and the only way to get access to university is in spite of them (with a dedicated teacher or an extremely hard-working student) not because of them. In fact grade 8 students attending fee-charging schools (quintile 5) are two to four times more likely to qualify for university than those attending no-fee schools (quintiles 1-4).

Yes there are exceptions to all of the above. Fee-charging schools do admit some students (perhaps 10-15%) that cannot pay fees, and some that pay partial fees. They also offer scholarships and bursaries. Similarly there are some extremely poor no-fee schools that succeed in spite of the odds – often because of a resilient principal. Yet these are exceptions to the rule or apply only to a small minority.

While the education crisis that South Africa finds itself in has its roots in the apartheid regime of institutionalized inequality, this fact does not absolve the current administration from its responsibility to provide a quality education to every child in South Africa not only the rich. After 21 years of democratic rule most Black children continue to receive an education which condemns them to the underclass of South African society, where poverty and unemployment are the norm, not the exception. This substandard education does not develop their capabilities or expand their economic opportunities, but instead denies them dignified employment and undermines their own sense of self-worth.

In short, poor school performance in South Africa reinforces social inequality and leads to a situation where children inherit the social station of their parents, irrespective of their own motivation or ability. Until such a time as the Department of Basic Education and the ruling administration are willing to seriously address the underlying issues in education, at whatever political or economic cost, the existing patterns of underperformance and inequality will remain unabated.

*The 88% figure is calculated using the 2015 Q1 DBE Masterlist and only counting as ‘fee-paying’ those schools that were categorised as “No” for ‘NoFeeSchool’. It is not clear what the fee status is of the schools that are currently listed as “To Be Updated” and “Not Applicable”. For conservative estimates I would go with 66% from the Action Plan (see pg50 here). The figures for the number of ex-Model C schools were also taken from the 2015 Masterlist – see “ExDept”.

//

Dr Nic Spaull, from the Research on Socio-Economic Policy group at Stellenbosch University, is a contributor to the South African Child Gauge 2015, which focuses on youth and the intergenerational transmission of poverty. The publication was/will be released this week by the Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town and is available on www.ci.org.za.

- My @Powerfm987 interview on the Child Gauge 2015 where we spoke about education, reading by age 10, school fees and inequality, teacher training, priorities and whether or not government is working with researchers in education (short answer: yes, but probably not enough)

Nice article!

Sent from my Samsung Galaxy smartphone.

As always Nic, your clarity is spot on. Saying it like it is, as ever. Thank you for your continued voice from so far away.

Kathryn Torres, Shine.