(The article below first appeared in the Financial Mail on 15 July. The unedited version is available below and their slightly edited version is available here).

A National Reckoning

The impacts of COVID-19 on employment, hunger and inequality

– Nic Spaull

The coronavirus pandemic is the largest social and economic shock in our lifetimes. It has fundamentally interrupted everything we do and exacerbated existing problems like poverty, inequality and unemployment. The collateral damage of this one virus has been profound and will be with us for the next 10 years, if not longer. While the South African government acted swiftly and decisively to limit the spread of the coronavirus, implementing a nationwide lockdown within 7 days – arguably necessary and defensible – these mitigation measures have come at a high cost. Never before have we seen so much damage caused in such a short space of time, at least not in the last 50 years. This includes damage from the lockdown, the recession and the pandemic itself. As will become evident in this essay, the true scale of job loss and hunger throughout South Africa is difficult to fathom. We estimate that between February and April 2020, 3 million South Africans lost their jobs, and a further 1,5 million lost their income (through being furloughed). Furthermore, losses were concentrated among women who accounted for 2 million of those 3 million job losses. Half of all respondents (47%) reported losing their main source of income. These are sobering results. In this essay I will summarize the findings of the 11 research papers that were released on the 15th of July focusing on two related areas: employment and hunger.

Over the last three months, and together with 30 leading social science researchers, we have surveyed over 7000 South Africans from the length and breadth of our country. Using 50 call center agents and interviewing in 10 languages, we administered a 20-minute telephonic questionnaire asking respondents about their employment, household hunger, migration, and receipt of grants. This study, the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) is the largest non-medical COVID-19 research project currently underway in South Africa. Our sample was drawn from, and is representative of, a previous survey – the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS). NIDS was a nationally representative sample of South Africans in 2008 who were selected to be part of the study and have subsequently been visited every 2-3 years, with follow-up surveys in 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2017. Hundreds of academic papers have been written using this study. Earlier this year we were given permission by the Presidency to use the NIDS sampling frame for a new ‘NIDS-CRAM’ study. Due to the operational constraints around surveying people during a pandemic, and the limitations of telephone surveys compared to in-person surveys, this latest iteration has a much shorter questionnaire and a smaller sample size than previous rounds of NIDS. (See also the essay by Andrew Kerr and his co-authors on representivity). While these caveats should not be brushed over, and they are readily and freely acknowledged by the researchers, it is also our view that the trends evident in the NIDS-CRAM data are indicative of the underlying labour market and welfare dynamics in South Africa today. It is also the only broadly nationally representative survey currently available. As the authors in this special issue, we all agree with economist Stefan Dercon when he says that “waiting for better data is not an option: decisions have to be made now as this risks turning into a disaster, not just for health, but also for people’s livelihoods.” And it is to livelihoods that I would now like to turn and summarise some of the findings emerging from the data.

Unprecedented job losses

During our survey in May and June, the NIDS-CRAM survey asked respondents whether their household had lost its ‘main source of income’ since the start of the lockdown on the 27th of March. A staggering two in five respondents (40%) reported that they had. This has profound consequences for welfare and hunger in South Africa. An underappreciated fact in South Africa is that grant-receiving-households also rely heavily on income earned from the labour market, not only income from grants. Gabrielle Wills and her co-authors show that 39% of grant-receiving-households reported that income from wages was the main source of income, compared to 70% for non-grant-households. If many people lost their job, were furloughed, or were locked-out of their income (for example informal traders), this helps explain the sharp increase in reported hunger that we see in the survey. So, how many people lost their income?

The survey asked respondents a number of retrospective questions about employment and income in both April and February allowing us to compare job losses and income losses over this period. In their paper Vimal Ranchhod and Reza Daniels find that 1-in-3 income earners in February (33%) did not earn an income in April. The weighted NIDS-CRAM data further shows that there was an 18% decline in employment between February and April 2020. In terms of real numbers, the estimate is that there were 17 million people employed in February but only 14 million in April 2020, i.e. that 3 million people lost their jobs. A further 1,5 million (9%) were furloughed. That is, they received no income but reported they had a job to return to. If these numbers are true, the scale of this job loss is unprecedented in South African history.

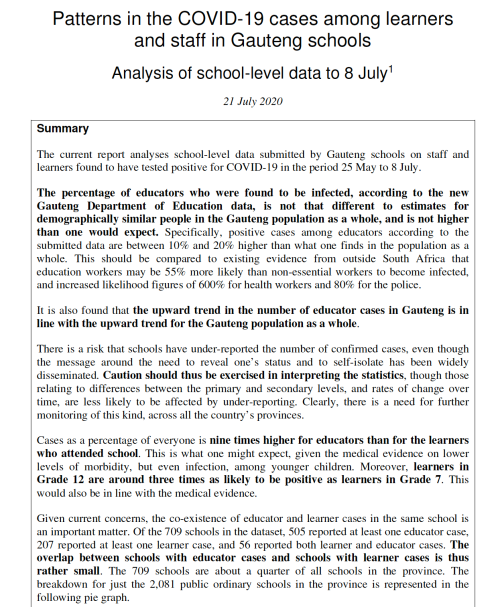

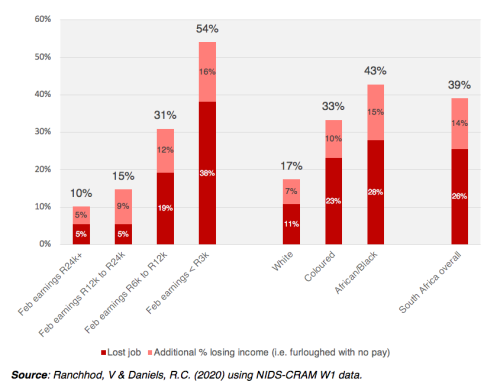

The next important question is who are we talking about? Who lost their jobs? Who lost their income? It turns out that job losses were most severe for those who were already disadvantaged in the labour market. The rates of net job loss are much higher for manual labourers (-24%) compared to professionals (-5%), for those with verbal contracts (-22%) compared to those with written contracts (-8%), for women (-26%) compared to men (-11%), and for those with a tertiary education (-10%) compared to those with matric or less (-23%). The graph below draws on data from the paper by Ronak Jain and her co-authors and starkly illustrates the disproportionate nature of net job losses and income losses (furlough).

Figure 1: The net percentage of respondents experiencing job loss (i.e gains minus losses) or furlough (an employment relationship but no income) in the working age population: February to April 2020

It is important to note that the data reported by Ronak Jain and her co-authors is “net job loss”, i.e. it takes account of the people (albeit a smaller percentage) who gained jobs over this period. In another paper, Vimal Ranchhod and Reza Daniels look specifically at job loss (not net job loss) among those who were employed in February, and report this by income and race (Figure 2). What is clear is that Black people were three times more likely to lose their job (28%) compared to White people (11%), and that those earning less than R3,000 a month were eight times more likely to lose their job (38%) compared to those earning more than R24,000 a month (5%).

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents experiencing job loss or furlough (an employment relationship but no income) in the working age population February to April 2020

Clearly the collateral damage of the lockdown has landed disproportionately on the poor who are also more likely to be in the informal sector, have lower earnings, are less educated, and are more likely to be Black African. This finding is corroborated by all the NIDS-CRAM papers looking at employment.

Women face a double disadvantage

One final trend that is perhaps most clear across all domains is that this pandemic and the job losses it has left in its wake have fallen most heavily on women. Of the approximately 3 million net job losses between February and April, women accounted for 2 million, or two thirds of the total. Daniela Casale and Dori Posel show that among those groups of people that were already disadvantaged in the labour market, and already faced a disproportionate share of job losses from the pandemic (the less educated, the poor, Black Africans and informal workers), women in these groups faced even further job losses, putting them at a ‘double disadvantage.

Hunger

Given what we know now about the extent of job losses and income losses it was inevitable that household hunger would rise. This is clearly what the data shows. Half of all respondents (47%) reported that their household ran out of money to buy food in the month of April. This ‘monthly figure’ is double the ‘annual figure’ reported in the General Household Survey (GHS). 21% of households in the GHS reported they ran out of money to buy food at some point in the last year.

Looking specifically at reported hunger and depth of hunger in NIDS-CRAM, 1-in-5 (21%) respondents indicated that someone in their household had gone hungry in the past week. 1-in-8 (13%) reported frequent hunger (3+ days / week) and 1-in-14 (7%) reported perpetual hunger (every day or almost every day in the week). The same questions were repeated asking specifically about child hunger. In households with children, 1-in-7 respondents (15%) indicated that a child had gone hungry in the last week because there wasn’t enough food. 1-in-13 (8%) reported frequent child hunger (at least every other day), and 1-in-25 (4%) reported perpetual child hunger (child hunger every day or almost every day).

Figure 3: Reported hunger in the last seven days (asked separately for “anyone in the household” and children (<18 years).

Source: Van der Berg et al., 2020 using NIDS-CRAM Wave 1 data weighted.

In a set of reports that makes for disturbing reading, there is also clear evidence of altruism, sacrifice and resilience within poorer households. The best example of this is the practice of “shielding” where households report adult hunger but not child hunger. In households that experienced hunger in the past week, nearly half (42%) managed to ‘shield’ children from that hunger, despite adults going hungry in the household. Where adult hunger was less than 4 days per week, the practice of shielding is higher (47%), but where adult hunger is perpetual (almost every day or every day) fewer households seem able to shield their children from hunger since only 33% reported that children did not go hungry in those households. It would seem that in times of acute crisis, like this pandemic, many households have managed to protect or ‘shield’ their children. But this protective capacity of households has its limits; where adult hunger becomes too pervasive, households seem unable to protect their children from hunger.

While the employment losses reflect on the period February to April (and before the roll-out of the government’s COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant), the hunger questions reflect on the “last 7 days.” Given that this survey was done in May and June, and that government grants were topped up from the beginning of May, these hunger figures are after households have received grant top ups (note also that these top ups were largest in May).

Capacity to prevent and capacity to provide

The severely delayed roll-out of the COVID-19 grant and UIF payments to those who have lost their jobs or incomes, reflects the difficulty of rapidly implementing social relief. This is in stark contrast to the rapid pace at which the lockdown was implemented. On the one hand government implemented a hard lockdown swiftly and severely, deploying the army across the country within 7 days of the announcement. On the other hand, government has taken more than two months to provide any form of relief to those most affected by that same lockdown. Two months after at least 4,5 million South Africans lost their income (3 million from job loss, 1,5 million from furlough) only 117,000 people (3% of that number) had received the Special COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant. That 117,000 number is the official number of payouts up to the 31st of May 2020. Clearly governments ability to prevent (travel, socialising, commerce) is far greater than its ability to provide. This lopsided capacity of government is critical in understanding why hunger has risen to unprecedented proportions.

Knowing what we know now about the collateral damage of a nationwide lockdown, including who it affects and how it affects them, as well as knowing what we know now about government’s administrative and financial capacities to provide, we should exercise extreme caution before again implementing a nationwide lockdown. While hindsight is 20:20, we can all acknowledge that the great uncertainty around the pandemic justified the lockdown (at least initially), but going forward other mitigation measures like implementing social distancing will have to be found and pursued with greater vigor. Preventing COVID-19 deaths should clearly be one of the top priorities of government, but it cannot come “at any cost.”

What is to be done?

There is a saying in banking that “it’s only when the tide goes out that you realize who has been swimming naked.” This refers to liquidity positions when there is a run on the bank or a financial crisis, but it is equally applicable here. It is only in times of crisis that we are able to see the true nature of things. In our case, the true nature of South African society. We have always known that there are large inequalities between the rich and the poor in our country, and that these inequalities are heavily determined by the colour of your skin, the place of your birth and the wealth of your parents. All of that is now uncomfortably laid bare in front of us. The pandemic has forced on us the unwelcome realization that we are only as safe as the least among us. “Your health is as safe as that of the worst-insured, worst-cared-for person in your society. It will be decided by the height of the floor, not the ceiling” (Anand Giridharadas).

We know that one of the true measures of a country is whether it can provide basic dignity for all who live in it. In our context this means enough food to eat, warm running water in a safe and dignified shelter, and access to essential healthcare and basic education. Of course, this is not the ceiling of our aspirations, which might include things like meaningful employment, higher education, art and cultural production etc. Rather we are speaking about the floor of our obligations to each other as citizens of the same country.

This is not usually something we think about when talking about budgeting, tax rates or property laws, yet it is very much at the heart of what it means to be civilized. How will we feel about our collective selves if we continue to turn our backs on the least among us simply because it is “legal” to do so? What is legal is not always ethical, and quite often not what is moral.

Which brings us back to inequality. Three months ago, Aroop Chaterjee and his co-authors published an important study analyzing South African tax data and showed that the richest 10% of South Africans own 86% of all wealth and the richest 1% own half of it (55%). Furthermore, the richest 3,500 individuals alone own more wealth than the poorest 32-million people in the country (the poorest 90%). Of course, all of this is strongly racialized. White South Africans make up the majority (60%) of the richest 10%. One doesn’t have to be a statistician to do the maths here; white South Africans own at least half of the country’s wealth despite being only 9% of the population.

Figure 4: Shares of total South African wealth using tax data (Source: Charterjee et al., 2020: p20)

The pandemic is a rare opportunity to reflect on the country we have inherited and the country we are building. To recognize in earnest that the pre-pandemic South Africa only worked for a few and that people like me and you will have to agree (or at the very least accept) that we will need to share more of our wealth and privileges going forward. Both through new private acts of generosity and new public forms of redistribution.

That is what the situation requires. As Van der Berg and his co-authors explain in their NIDS-CRAM paper, “Social grant top-ups must continue beyond October. The severity of the economic shock and the depth of poverty make this imperative, despite fiscal constraints. Although top-ups are inadequate to compensate for other income and job losses in many households, the most common social grants, the Old Age Pension and the Child Support Grant (CSG), inject much needed financial resources into many poor households.” Furthermore, they argue that the CSG top-ups must be paid per child not per caregiver, and must increase if they are to prevent further child hunger. Gabrielle Wills and her co-authors come to a similar conclusion: “To stave off mass, chronic hunger we simply cannot let up on the support being provided to households … Failure to do so will deepen an emerging humanitarian crisis, hamper economic recovery and threaten socio-political stability.”

All of this will cost a lot money that the state does not currently have. Either we must find new social compacts and mechanisms to share wealth, income and opportunity, or we will continue towards our dystopian future, with islands of excess sitting precariously on a sea of poverty.

It is obvious that the willingness of the rich to part with some of their wealth – especially when compelled to do so via government – is far greater when there is a trust that the money will be used wisely, by competent and ethical bureaucrats and to achieve goals we can all believe in. That means that government will need to clean house and show their own moral integrity before they call on rich South Africans to do likewise. Appoint clearly competent and ethical technocrats to lead key initiatives and deliver results. Put in place consequences for non-performance and inept bureaucrats, and jail corrupt politicians. Realistic targets with reasonable time frames must be met with success or resignations. Build 400,000 new houses and apartments within the next two years. Eradicate pit-latrines within two years. What is the reason why these things cannot be done? Perhaps most importantly, a competent development State is also necessary for long-term economic growth since redistribution can only take us so far. Ultimately the economy will also have to start growing and employing large numbers of people.

While there has been some tinkering around the edges of the political and economic possibilities available to us, nothing we have done has made inroads into the gross income inequality that characterizes our country. And now with a pandemic on our doorstep, a decimated labour-market, and a hunger crisis not far behind it, where are we to turn?

One thing that is clear is that business as usual will not cut it. Like those resilient parents who manage to shield their children from hunger, it will require altruism and sacrifice. That is because, like those parents, there really are limits to the poor’s benevolence. I recall being told about a popular slogan during the democratic transition that went something like this: “If they don’t eat, we don’t sleep.”

There is no longer any room for the fat of corruption, or the waste of ineptitude. But similarly, there is also no room for those who cannot see the basic dignity inherent in all people. A dignity that is currently being eroded. I have little doubt that this pandemic will be the straw that broke the camel’s back in South Africa. Whether that is for good or for ill, remains to be seen. I also have no doubt that South Africa has the skills and the moral conscience to forge a new and better path, but it will require decisiveness and clarity of vision, and above all, leadership.

President Ramaphosa, I know you already know this; don’t waste a good crisis. Leadership requires courage and moral integrity. Be bold.

//

Nic Spaull is the Principal Investigator of the NIDS-CRAM study. The views expressed here and those of the author not necessarily those of the other NIDS-CRAM researchers. All papers are available at cramsurvey.org. and the NIDS-CRAM data is freely available for download on the DataFirst website.