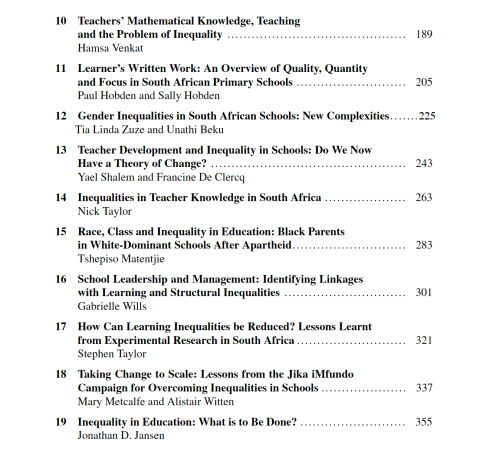

On Thursday this past week we launched our new book “South African Schooling: The Enigma of inequality” published by Springer. Jonathan Jansen and I co-edited the book which includes 19 chapters from some of South Africa’s leading scholars. The chapters are as follows:

The reason why we wanted to write this book was twofold: (1) Books are a nice way of bringing together in one volume the latest ‘state of play’. (2) We thought it would be helpful to have a single book with contributions from both educationists and economists who otherwise rarely read each other’s work. To give you a sense of the book I have included an excerpt below from my framing chapter of the book.

Chapter 1. Equity: A Price Too High to Pay?

Nic Spaull

1.1 Introduction

South Africa today is the most unequal country in the world. The richest 10% of South Africans lay claim to 65% of national income and 90% of national wealth; the largest 90–10 gap in the world (Alvaredo et al. 2018, p. 150; Orthofer 2016). Given the strong and deeply historical links between education and the labour market these inequities are mirrored in the education system. Two decades after apartheid it is still the case that the life chances of the average South African child are determined not by their ability or the result of hard-work and determination, but instead by the colour of their skin, the province of their birth, and the wealth of their parents. These realities are so deterministic that before a child’s seventh birthday one can predict with some precision whether they will inherit a life of chronic poverty and sustained unemployment or a dignified life and meaningful work. The sheer magnitude of these inequities is incredible. In 2018 the top 200 high schools in the country have more students achieving distinctions in Mathematics (80%+) than the remaining 6,600 combined. Put differently 3% of South African high schools produce more Mathematics distinctions than the remaining 97% put together. Of those 200 schools, 175 charge significant fees. Although they are now deracialized, 41% of the learners in these schools were White. It is also worth noting that half of all White matrics (48%) were in one of these 200 schools. This is less surprising when one considers that in 2014/2015, White South Africans still make up two thirds of the ‘elite’ in South Africa (the wealthiest 4% of society) (Schotte et al. 2018, p. 98).

In a few years’ time when we look back on three decades of democracy in South Africa, it is this conundrum – the stubbornness of inequality and its patterns of persistence – that will stand out amongst the rest as the most demanding of explanation, justification and analysis. This is because inequality needs to be justified; you need to tell a story about why this level of inequality is acceptable or unacceptable. As South Africans what is the story that we tell ourselves about inequality and how far we have come since 1994? Have we accepted our current trajectory as the only path out of stubbornly high and problematically patterned inequality? Are there different and preferential equilibria we have not yet thought of or explored, and if so what are they? In practical terms, how does one get to a more equitable distribution of teachers, resources or learning outcomes? And what are the political, social and financial price-tags attached to doing so?

While decidedly local, the questions posed above and in the subsequent chapters of this book also have global relevance. Like few other countries in the world, South Africa presents an excellent case study of inequality and its discontents. As Fiske and Ladd (2004, p.x) comment in their seminal book ‘Elusive Equity’:

“South Africa’s experience is compelling because of the magnitude and starkness of the initial disparities and of the changes required. Few, if any, new democratic governments have had to work with an education system as egregiously- and intentionally inequitable as the one that the apartheid regime bequeathed to the new black-run government in 1994. Moreover, few governments have ever assumed power with as strong a mandate to work for racial justice. Thus the South African experience offers an opportunity to examine in bold relief the possibilities and limitations of achieving a racially equitable education system in a context where such equity is a prime objective.”

Inequality touches every aspect of South African schooling and policy-making, from how the curriculum is conceptualized and implemented to where teachers are trained and employed. Reviewing the South African landscape there are many seemingly progressive policies on topics such as school governance, curriculum and school finance. As the chapters in this volume will show, few of these have realized their full potential, and in some instances, have hurt the very students they intended to help (Curriculum 2005, for example). The ways that these policies have been formulated, implemented and subverted are instructive to a broader international audience, particularly Low- and Middle-Income Countries and those in the Middle East and Latin America. The visible extremes found in South Africa help to illustrate the ways that inequality manifests itself in a schooling system. In a sense, the country is a tragic petri dish illustrating how politics and policy interact with unequal starting conditions to perpetuate a system of poverty and privilege. Ultimately, we see a process unfolding where an unjustifiable and illegitimate racial education system (apartheid) morphs and evolves to one that is more justifiable and somewhat non-racial, all the while accommodating a small privileged class of South Africans who are not bound to the shared fate of their fellow citizens. Based on their reading of the South African evidence, different authors paint a more, or less, pessimistic picture of South African education. Some authors focus on the considerable progress that has been made in both the level and distribution of educational outcomes since the transition, and particularly in recent periods (Van der Berg and Gustafsson 2019). Others document tangible interventions aimed at decreasing inequality by improving early grade reading outcomes in the poorest schools, principally through lesson plans, teacher-coaches and materials (Taylor S 2019). While generally supportive of these types of interventions a number of other authors caution that these gains are the low hanging fruits of an extremely underperforming system. Unless teachers have higher levels of content knowledge (Taylor N 2019), and meaningful learning opportunities to improve their pedagogical practices (Shalem and De Clercq 2019) any trajectory of improvement will soon reach a low ceiling. Moving beyond teachers’ competencies, the book also foregrounds deficiencies in funding (Motala and Carel 2019), and the primacy of politics (Jansen 2019).

The aim of this introductory chapter is to provide an overview of the key dimensions of inequality in education and in South Africa more generally, showing that outcomes are still split along the traditional cleavages of racial and spatial apartheid, now also complemented by the divides of wealth and class. The argument presented here foregrounds the continuity of the pre- and post-apartheid periods and concludes that in the move from apartheid to democracy the primary feature of the story is a pivot from an exclusive focus on race to a two-pronged reality of race and class. This is true not only of the schooling system, but also of South African society more generally. Where rationed access to good schools was determined by race under apartheid, it is now determined by class and the ability to pay school fees, in addition to race. Rather than radically reform the former White-only school system – and incur the risk of breaking the only functional schools that the country had – the new government chose to allow them to continue largely unchanged with the noticeable exception that they were no longer allowed to discriminate on race and they were now allowed to charge fees.

//

The full intro chapter and chapter titles are available here. The book can be ordered here. We will be having a few more book launches (in Joburg and possibly overseas), I’ll post those either on here or on Twitter.

🙂

Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.

Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.