On International Literacy Day, the 8th of September 2021, The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) launched the “Right to Read and Write” at the Constitutional Court. I was one of nineteen authors who contributed to the report over the last two years. I think it is a landmark document and encourage everyone to read it (full report here). I will include only the Preamble and Postscript here to give you a sense of the document, but it is worth reading the whole thing! Minister Motshekga’s short opening speech at the event is also worth watching.

_______________________________

The Right to Read and Write

Preamble

1.1 Introduction

South African society has one supreme law that stands over and above all others: the Constitution. It is the body of fundamental principles that outlines the legal foundation for the existence of our republic and states the rights and duties of its citizens and those we elect to govern us. One of those fundamental rights enshrined in the constitution is that “Everyone has the right to a basic education” (Section 29(1)(a))

In many senses this particular right is a special right in the Constitution and different from many others since it is ‘immediately realizable.’ Unlike the other socioeconomic rights in the Constitution – such as the rights to housing, to healthcare, to food, water, security, and further education – there is no qualification to the right to a basic education. There is nothing that says the state must work towards the ‘progressive realization’ of the right to a basic education, or that the realization of the right to a basic education is ‘subject to available resources.’ There are only two socioeconomic rights in the entire Constitution that are not subject to such limitations and progressive realization, and these are: (1) The right to a basic education (Section 29(1)(a)) and (2) Children’s core socioeconomic rights to ‘basic nutrition, shelter, basic health care services and social services’ (Section 28(1)(c)) This was not an accident. In their wisdom, the drafters of the Constitution recognized that in addition to other necessary measures of redress, it was only through the systematic prioritization of the next generation that South Africa would be able to transcend the multifaceted and far-reaching consequences of apartheid.

When the South African Constitution was being written, it was expressly noted and understood that education would hold a privileged place in the new democratic dispensation. Neither redress nor prosperity would be possible without it. The Constitution’s mandate to ‘free the potential of each person’ was contingent on the realization of this right for all who live in the country. As Constitutional Court Justice Bess Nkabinde ruled:

‘‘The significance of education, in particular basic education, for individual and societal development in our democratic dispensation in the light of the legacy of apartheid, cannot be overlooked… [B]asic education is an important socioeconomic right directed, among other things, at promoting and developing a child‘s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to his or her fullest potential. Basic education also provides a foundation for a child‘s lifetime learning and work opportunities”

– Governing Body of the Juma Musjid Primary School v Essay.

While the unqualified right to a basic education has not been legally contested, it is still not entirely clear what is (and is not) included when one speaks about a ‘basic education’. The Constitution itself does not provide an explication of this right which specifies how it is to be realized and what conditions would need to be met for this right to be said to have been realised or not.

In 2013 the Minister of Basic Education prescribed the Regulations Relating to Minimum Uniform Norms and Standards for Public School Infrastructure which set out the ‘necessary resources’ that form the minimum core of this right in terms of infrastructure. Subsequent court interpretations of these regulations demonstrate that South Africa now has a set of defined norms for basic physical infrastructure such as running water, electricity, sanitation, and a safe built-environment (Equal Education v Minister of Basic Education 2019 (1) SA 421, ECB), as well as basic educational materials such as one textbook per subject per child (Minister of Basic Education and Others v Basic Education for All and Others [2016] 1 All SA 369, SCA). This has gone some way to make explicit what the State’s minimum obligations are in the fulfilment of this right, at least in terms of infrastructure and textbooks. To that extent it has begun to explicate or ‘unpack’ the meaning of the right to a basic education by specifying its minimum content.

However, what has been lacking in much of this unfolding process is the specification of minimum outcomes that must be met for the right to a basic education to be said to have been realized for an individual. What is the minimum set of knowledge, skills and dispositions that an individual must possess for their right to a basic education to be said to have been realized? Alternatively, are there certain specific measurable ‘core’ outcomes that, if a child is unable to achieve them, one can say definitively that their right to a basic education (or at least some fundamental component of it) has been denied?

It is the contention of this background paper that one of these minimum ‘core’ outcomes with respect to the right to a basic education, is that a child must be able to read and write with understanding at a basic level, in their home language, by the age of ten. Put differently, this fundamental skill is one of the tools by means of which the constitutional promise is to be fulfilled. Unless and until the child is educated to the requisite minimum level, the constitutional promise remains unfulfilled. The purpose of this document is to provide a clearly articulated, evidence-based, and measurable definition of what it means to “read and write, with understanding, at a basic level.” In so doing it aims to operationalize this right by making one additional core component of the right to a basic education explicit. This component would be the “Right to Read and Write.” Whilst it is clear that the right to a basic education envisaged in the Constitution goes well beyond merely the ability to read and write, it is equally clear that if a child is denied this most basic skill (to read and write with understanding) they have at the same time, also been denied the right to a basic education.

In the same way that the government, the courts and civil society now have a shared understanding of the physical resources that are necessary for the realization of the right to a basic education (textbooks, toilets, teachers etc.), the intention of this document is to move towards a similarly shared understanding of the content of the right to a basic education with respect to outcomes, and to do so by providing a clearly articulated, defensible, measurable, and research-informed definition of what it means to read and write at a basic level.

…

Postscript

The Constitution of South Africa was, and is, one of the landmark achievements of our young democracy. It sets out the rights and obligations of citizens and those we elect to govern us, as well as charting a course to a non-racial society founded on ‘human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.’ While the Constitution is clear and unequivocal – everyone has the right to a basic education – it is the ongoing task of civil society, government, legislature, and the judiciary to explicate what that means. Rights are not self-fulfilling, nor obligations self-evident.

It has been the aim of this document to put forward a defensible explication of one core component of the right to a basic education, and that is the ‘right to read and write.’ It is our contention here that no child can reach their full potential without being able to read and write for meaning and pleasure. We believe that if that is the case then the onus is on us to find a way to measure this right and whether it has been realized.

By drawing on a wealth of experience and research we have attempted to put forward an evidence-based argument for what it means to read and write at a basic level. It is the role of the Executive branch of government to decide whether it agrees with the above interpretation of this component of the right to a basic education. And it is the role of the Judiciary to adjudicate whether the Executive’s actions and interpretations of this right are in keeping with the text, spirit, and ethos of the Constitution.

The Right to Read and Write:

“Every child in South Africa has the right to read at a basic level, in their home language, by the age of 10. That is to say, they can read and understand a short and simple text and answer 80% of the literal and straight-forward inferential questions they are asked that are based on that text. Approximately 60-80% of these questions should be classified as ‘Very easy’ or ‘Easy’ questions.

“Every child has the right to write at a basic level, in their home language, by the age of 10. That is to say that they can express themselves in writing by using a collection of simple and related sentences with correct grammar and punctuation.”

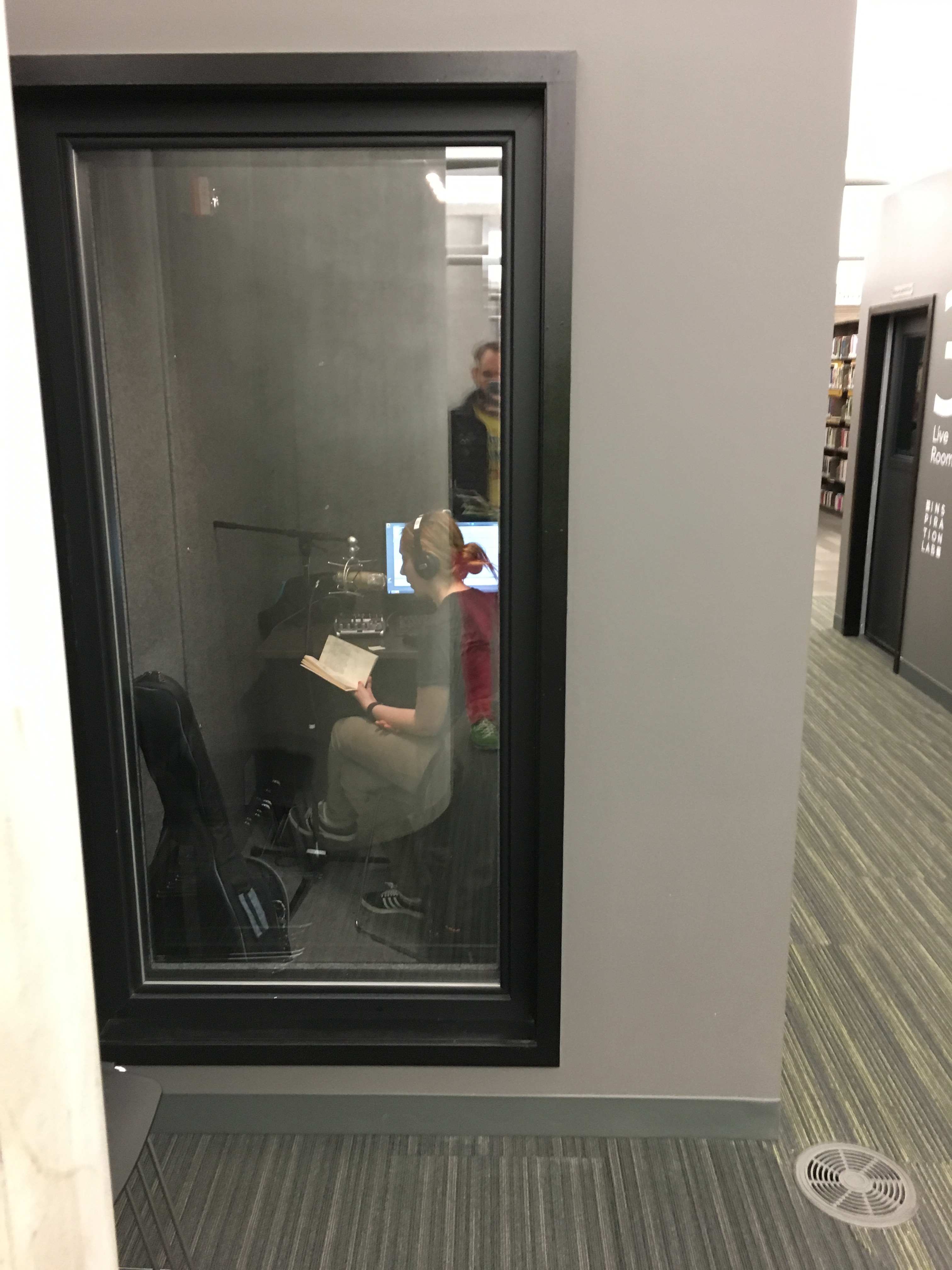

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

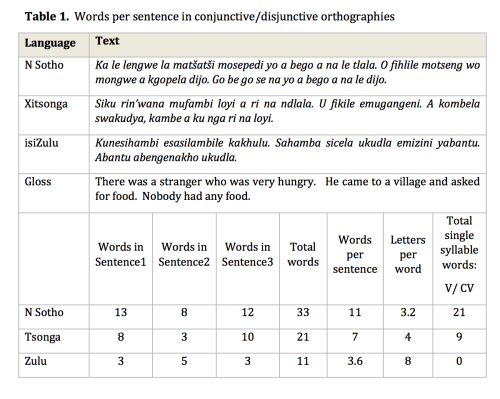

For those who are unfamiliar with oral reading fluency, it is the speed at which written text is reproduced as spoken language, or put more simply, it is how quickly and accurately you can read aloud. It is one of the components of the “

For those who are unfamiliar with oral reading fluency, it is the speed at which written text is reproduced as spoken language, or put more simply, it is how quickly and accurately you can read aloud. It is one of the components of the “