NEEDU 2013: Moving from Form to Substance

Guest blog post by Gabrielle Wills

The NEEDU 2013 report entitled “Teaching and Learning in Rural Primary schools” has finally entered the public domain. Subsequent to the release of the first NEEDU 2012 report, sensational headlines in the press presented certain findings that were isolated from the wider objective of the report. This potentially misrepresented both the objective of the report and the much needed role of NEEDU, which (as its name suggests) is the national evaluator of education. It is no surprise then that the 2013 report has been withheld from public view, delaying constructive dialogue and systems thinking that will emerge out of this insightful material. Compared with the press’ responses to the release of NEEDU 2012, media reporting has been somewhat less damaging in its representation of the findings this time round. However they have still not conveyed the most pertinent messages of the report. This article is intended to direct the reader to the report’s substance.

Before considering the details, a noted conceptual contribution of the report is this: it moves towards being systemic in its evaluative approach, even when considering individual elements that make up the whole. In Lant Pritchett’s book “Rebirth of Education” he draws on Howard Gardener’s (1991) evocative phrase, arguing that we live with an “unschooled mind” about systems. Many activities and research undertaken in the field of education and education economics are modular, focusing on aspects or isolated interventions without considering how these link together within the wider system. NEEDU 2013 moves beyond just a discussion of just individual symptoms of a broken system, of which we are becoming acutely aware (for example poor teaching content knowledge and absurdly low levels of learning in the classroom), getting closer to the institutional inefficiencies that must be addressed before we can move forward.

Much of the discussion of the report is framed under two headings: accountability and instructional leadership. The first is a term with which most economists are well-familiar (and our education system far less so). However the notion of ‘instructional leadership’ is used in the education administration literature, usually in reference to school leaders and the extent to which they organise the school environment to focus on the core business of the school, namely learning. The report extends this terminology to wider administration at the district, provincial and national level to consider that the management of curriculum, assessment and resources will have a strong bearing on learning improvements.

“Instructional leadership may be thought of as the ensemble of processes, operating at different levels of schools, and directed towards leading the system to improved quality (NEEDU 2013, pp 13)”.

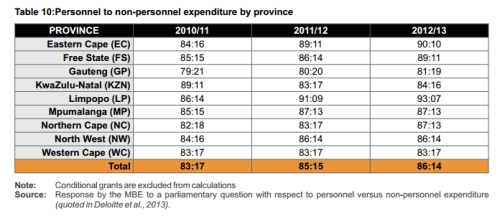

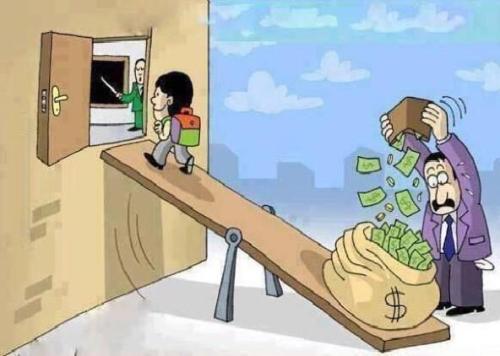

One of the most important processes within this ensemble is the management of human resources and particularly the post provisioning process, recruitment and promotion, and professional development. “HR management is the single most important tool available to PDEs (provincial directorates of education) in giving effect to curriculum policy. It provides the tools for the optimal deployment of the costliest and most important resource, educators.” The discussion draws our attention to how provinces have lost control of the post provisioning process, which has the largest budgetary implications for the department (and arguably national spending). The provincial personnel-non-personnel spending split should be 80:20 but has become increasingly skewed towards personnel, impeding on the system’s ability to deliver non-personnel resources to schools.

Without discipline in spending, the stability of provincial departments to execute functions is severely threatened. This has far reaching consequences for system functionality. It follows that the first three recommendations of the report, and rightly so, are that post provisioning norms and standards need to be unambiguously communicated and applied where strengthening education management information systems aids this process. It also highlights how the process of post provisioning and the recruitment and promotion of personnel must be removed from the influence of the predatory behaviour of organised interest groups.

Strongly related to instructional leadership, the report raises the importance of monitoring and evaluation required within education. However, much of what is being done in this regard takes on a ‘form’ of these things yet lacks any substance. This quotation sums it up well:

“.. in large parts of the system and with respect to a number of instructional leadership processes, both systems management and teachers are going through the motions, with little impact on the objects of their attention… Activity does not necessarily signify progress: there is a great deal of instructional leadership activity throughout the system, but much of it is undertaken at too superficial a level to make any impact on the quality of teaching and learning… If going through the motions is the first step towards effective instructional leadership, then engaging with the substance of the activities is the next (NEEDU 2013, pp 48).”

This is an acutely important observation. In reading recent Annual Plans and Annual Reports prepared by the DBE there is great deal of activity and forms of monitoring taking place. In many ways, some activities have been admirable and NEEDU 2013 directly acknowledges such successes. Yet many activities are divorced from the objective of improving learning. Consider the following examples:

- The quality of management in school is being monitored using perfunctory checklists of certain documents such as school improvement plans (SIP) and up-to-date records. But the majority of schools have a SIP and documents can readily be organised and kept up to date even in the presence of incompetent leaders. What is required is hiring the best leaders, on the basis of expertise not years of service or political affiliation. What is required is monitoring their performance using proven instruments of assessment rather than a checklist of activities accomplished.

- There is no doubt that the introduction of ANA has signalled a major step forward in monitoring whether the system is working. However these are neither standardized tests in the sense that year-on-year comparisons are possible, nor are the majority of schools and districts using these effectively to identify learning gaps. ANA is a form of monitoring yet currently lacks substance in influencing learning or even simply monitoring systemic progress.

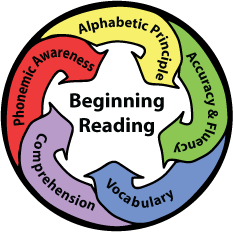

While focusing on institutional inefficiencies, NEEDU 2013 does not shy away from obvious problems of addressing teaching in the classroom. In recommendations five and six, the need for a roll-out of a proven reading and writing programme as well as primary numeracy and mathematics programme is expressed. Recommendation nine focusses on addressing teacher proficiencies through educational development, calling for considerable investigation into the teacher education sector and whether it is equipping graduates with necessary competencies. Despite great intentions to improve education and accompanying strategies, it is currently not possible given inherent capacity constraints of both teachers and administrators.

The time of window dressing activities that hide systemic weaknesses has continued for too long. We must move away from forms of activity that mimic best practice while neatly steering away from threatening fundamentals on the surface. Systemic weaknesses must be seen and acknowledged for what they are, and action taken to address them. In this regard, the recommendations of the report should be strongly considered.

________

Gabrielle Wills is a PhD candidate at Stellenbosch University and is part of the RESEP team. Her latest research is titled “A profile of the labour market for school principals in South Africa” which she presented at a conference earlier this year (PPT here).

For those who are unfamiliar with oral reading fluency, it is the speed at which written text is reproduced as spoken language, or put more simply, it is how quickly and accurately you can read aloud. It is one of the components of the “

For those who are unfamiliar with oral reading fluency, it is the speed at which written text is reproduced as spoken language, or put more simply, it is how quickly and accurately you can read aloud. It is one of the components of the “

of Education: (1) Chief Education Specialist: Education Planning and Information, and (2) Chief Education Specialist: Education Research. The full description (requirements, remuneration, etc.) can be found

of Education: (1) Chief Education Specialist: Education Planning and Information, and (2) Chief Education Specialist: Education Research. The full description (requirements, remuneration, etc.) can be found