The aim of the Q&A series is to get an inside look into some of South Africa’s leading education academics, policy-makers and activists. This is the eighth interview in the series. Doron Isaacs is the Deputy General Secretary of Equal Education (Twitter: @DoronIsaacs).

The aim of the Q&A series is to get an inside look into some of South Africa’s leading education academics, policy-makers and activists. This is the eighth interview in the series. Doron Isaacs is the Deputy General Secretary of Equal Education (Twitter: @DoronIsaacs).

1) Why did you decide to go into education and how did you get where you are?

It wasn’t so much a decision to go into education, as a decision to work in a poor community in order to help young people organise themselves to claim their rights and fight inequality. This involved building a small organisation, which became Equal Education.

When I was in my final year of law school at UCT I became interested in the role the legal system could play in the hands of progressive social movements. I wrote a paper about the efforts in the United States, during the second half of the 20th century, to use the courts to integrate and equalise schooling. It was eventually published in the SA Journal of Human Rights. That work helped me to understand that I didn’t want to practise as a lawyer at that time, that law alone is a fairly weak instrument, and that deep progressive social change is only produced through large movements of informed and organised poor and working-class people.

2) What does your average week look like?

It is usually very full. I work in Khayelitsha at the EE head office. There are many meetings each week. One is with about 50 core staff members of Equal Education. Another is with a team of facilitators – post-matrics who have grown up in EE, and now organise high school students – to plan content for the weekly youth group meetings that take place across the city. Sometimes I attend a march, or facilitate a discussion. On Thursday evenings we have seminars which are open to the public. There are many projects EE runs, from our youth film school, to the school libraries, to camps and seminars, campaigns, court cases, and work elsewhere in South Africa. In addition to being a staff member at EE, I was elected, at the July 2012 Congress, onto its National Council and Secretariat, and those governance structures meet periodically. I also sit on the boards of other organisations: the Equal Education Law Centre and Ndifuna Ukwazi. I try to read every day, and occasionally find time to do some writing. I have seldom been bored over the past six years.

3) While I’m sure you’ve read many books and articles in your career, if you had to pick two or three that have been especially influential for you which two or three would they be and why?

When EE began in early 2008 the question of what to do about OBE was important and topical. I was curious to understand how pedagogy with such progressive intentions was damaging working class children. A book called Education and Social Control, by Rachel Sharp and Anthony Green, which looked at so-called progressive education in the UK in the 1970’s, was a truly fascinating account of why extreme learner-centeredness can be socially retrogressive. A piece by Jo Muller, which connected me to Gramsci’s thoughts on the subject, was very helpful.

You know, just seeing the numbers on inequality had a big impact on me. EE used access to information law to make data on literacy and numeracy in the Western Cape publicly available. It showed that in 2009 only 2.1% of grade 6 kids in places like Khayelitsha were passing maths at 50%. Ursula Hoadley’s PhD thesis, which was a study of four Cape Town primary schools, showed me how inequality operates in education. Fiske and Ladd’s book, Elusive Equity, is still helpful in beginning to think about inequality. And I remember my eyes opening wide while reading a paper by your supervisor Servaas van der Berg where he showed that the socio-economic status of a school had a greater impact on academic performance than the socio-economic status of an individual child did (here, pg5). That really struck me, because it meant that investing in educational equality was a rational way to leverage social equality more generally.

When it comes to building organisation that can change society, there are so many good books. Two that come to mind are Steven Friedman’s Building Tomorrow Today about how the independent trade union movement was built here in the 1970s and 80s, and Parting the Waters, an epic account of the US Civil Rights Movement.

4) Who do you think are the current two or three most influential/eminent thinkers in your field and why?

My ‘field’ is not just ‘education’! Equal Education is about changing society, through changing the education system. We’re interested in the political economy of education. Many of us are excited to read Thomas Piketty’s new book, Capital in the 21st Century. That is serious thinking! There is a young education academic at Stanford named Frank Adamson – he’s great. We are incredibly lucky to have been able to learn directly from some marvellous thinkers and activists like Zackie Achmat, Mandla Majola, Rob Petersen, Paula Ensor, Vuyiseka Dubula, Mary Metcalfe, Mark Heywood, Peliwe Lolwana, Zwelinzima Vavi, Geoff Budlender and many others.

5) What do you think is the most under-researched area in South African education?

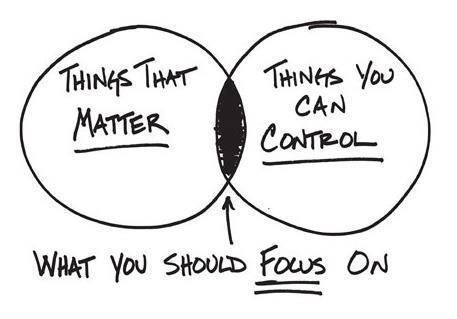

Well, take this provocative proposition: Achieving equal education would be a more potent way to build a socialist society than nationalising the mines or redistributing rural land. I’m not commenting on those last two right now, except to say that equal, quality, integrated education, from pre-school to tertiary level, would be a more radical and effective political program.

Okay that’s my provocation. Is anyone in South Africa doing research on education as a political and economic question? Is anyone even exploring what a transformed education system could look like? What its social impact could be? It’s being debated in healthcare around the NHI. Of course we need to fix teaching, textbooks and all that. But there is no imaginative thinking beyond that.

6) What is the best advice you’ve been given?

In 2008 we had one youth group in Khayelitsha. After a few months equalisers chose our first campaign, which was to fix 500 windows at Luhlaza High School. I’m not sure if I can call it advice, because it was their decision, but it was a vital lesson: in organising you start with small, visible things that can be achieved, and build from there.

7) If you ended up sitting next to the Minister of Education on a plane and she asked you what you think are the three biggest challenges facing South African education today, what would you say?

I think the Minister is fairly aware of major challenges facing education: teacher subject-content knowledge and motivation, text and textbook availability, school infrastructure conditions, and many others.

What I’d rather do is discuss certain dangers I see down the road. Testing is looming larger in our educational landscape. The matric results are the annual Holy Grail and the ANAs are on their way. I have concerns. Such intense focus on a few headline statistics could mean those stats lose their integrity. Matric results can be manipulated at all levels, including by schools who hold students back or push them out, driving up drop-out rates. Students are being pushed into Maths Literacy. In some cases schools are being closed because it’s a way to get rid of poor performance. What does she think?

There is a danger that this chorus of dismay about the public education system, and the need to fix it, turns into its opposite: a chorus for the false solution of privatising the schools. I think she’d agree, but I’d like to hear her thoughts on that.

The one thing I’d give her a hard time about is parents. I just don’t understand why the DBE doesn’t run massive campaigns to involve parents in education. There should be workshops in every community, often, about how to support your child, and how to support the local school. There is so much that could be done. EE has parent branches, but this is needed on a mass scale.

8) If you weren’t in education what do you think you would be doing?

I would love to have studied pure science. I’d also like to write history or biography. And I could see myself running a newspaper.

9) Technology in education going forward – are you a fan or a sceptic?

I’m in favour of technology, starting with providing electricity to the 3,544 schools currently without it. After that it would be great if the 75% of schools with no e-mail address could get connected, and if the 46% of schools with no telephone could get one.

I think technology has a lot to offer but I’m yet to be convinced that it can replace the teacher. Those first few years of school need to give children the joy and spontaneity of learning, but also and equally the discipline of learning. It is a gift to be inducted into being able to sit at a desk, on your own, concentrating, mastering, acquiring, processing. A genuinely educational classroom, created by a teacher, is an environment that poor and working class children will encounter nowhere else.

10) If you were given a R5million research grant what would you use it for?

I’m very curious to know whether the crisis of unemployed youth (3.1 million aged between 15 and 24 not in employment, education or training) can be partially dealt with by involving young people in our schools. Why can’t there be a national youth service with young people as sports coaches, librarians, teaching assistants, food-producing gardeners and much else?

11) Equal Education has been one at the forefront of the Minimum Norms and Standards case – do you think that we are likely to see more of this kind of “legal accountability” going forward? Furthermore do you think this is a positive development or not?

With EE the balance tilts towards people power, and away from lawyers. It’s been primarily a campaign of people, but the legal work which the LRC assisted us with also mattered. It enabled us to set out facts and arguments in a structured process, producing a powerful window onto education in this country. My colleague Yoliswa Dwane’s founding affidavit and replying affidavit are worth reading. The supplementary material put before the court by Debbie Budlender and Ursula Hoadley was great. I think the achievement of norms and standards for school infrastructure is big and very positive. We’re still busy with that work, because the new law must now be implemented!

12) Equal Education is a grass-roots organization with considerable links to the community and to students. In many countries around the world there is often a disconnect between what is happening at a national-policy level and what the reality is on the ground – do you believe this is also the case in South Africa? And if so, in which areas is this disconnect most apparent?

Government policy is often complicated. Take teacher post-provisioning for example. There is a mathematical formula used to calculate how many government-funded teaching posts a public school gets. It sits in an appendix to a regulation made in terms of the Employment of Educators Act. It is hard to find and harder to understand! And it is not pro-poor. And yet this formula plays a massive role in determining how about 80% of the education budget is spent.

An organisation like EE has to make policy accessible and open to debate. In Detroit a wonderful academic named Tom Pedroni runs a project to make education policy accessible to communities and activists. I wish progressive South African academics would set up a similar project together with EE.

13) What would you say are the three major difficulties faced by civil-society organizations in South Africa?

The work we do is very tiring and sometimes depressing. But somehow I feel motivated to work hard, and I like the people I’m with every day. All organisations struggle for funding – it is an ongoing battle and there is not yet a culture of giving to social justice organisations. We have over 200 people who give monthly to EE and we desperately need more. Another challenge is to connect our work to a broader social justice agenda. For example, our divided education system still rests on apartheid geography. Poor people live on the edges of cities and so aren’t zoned to attend better schools. Housing and urban land activists need to get together with education activists. This race and class-divided society also challenges how an organisation like EE must go about its work. We can’t pretend that we have our own little utopia where race, class and gender oppression have ceased to exist. We have to overcome these things amongst ourselves as we try to overcome them in society.

//

Some of the other academics/policy-makers on my “to-interview” list include Servaas van der Berg, Martin Gustafsson, Thabo Mabogoane, Veronica McKay, Hamsa Venkatakrishnan, Volker Wedekind, John Kruger, Linda Biersteker, Jonathan Jansen and Jon Clark. If you have any other suggestions drop me a mail and I’ll see what I can do.

This past week I was in New York en route to Boston and managed to get across to the incredible New York Public Library because they were having a special exhibition on children’s books: “The ABC of it: Why Children’s Books Matter” which I absolutely loved. While I am naturally interested in children’s literature (from a pedagogical, sociological and political perspective), the reason for my visit was because I am now an uncle and figured I need to get clued up on children’s literature for my (incredibly) cute nephew Lincoln William Spaull who will obviously be a reader. So here are a selection of photos of the exhibition and some of my comments…

This past week I was in New York en route to Boston and managed to get across to the incredible New York Public Library because they were having a special exhibition on children’s books: “The ABC of it: Why Children’s Books Matter” which I absolutely loved. While I am naturally interested in children’s literature (from a pedagogical, sociological and political perspective), the reason for my visit was because I am now an uncle and figured I need to get clued up on children’s literature for my (incredibly) cute nephew Lincoln William Spaull who will obviously be a reader. So here are a selection of photos of the exhibition and some of my comments… It actually reminded me of Frida Kahlo and her boldness…

It actually reminded me of Frida Kahlo and her boldness… But getting back to “Goodnight Moon”, the guide told us a fascinating story about a parent who read the story to her young son before he went to bed but then later she heard him crying and walked in to find him sitting on the bed with the book open and a foot on each page. The little boy loved the story so much that he was trying to climb into the room and was upset because he couldn’t get inside. I thought it epitomised the idea that children do not make the same distinctions as we do between fiction and reality – they are one and the same. Another story illustrating the same thing is the book “Little Fur Family” by Margaret Wise Brown. The author was so well known and established that she managed to convince the publisher to cover her book in real rabbit fur (this was 1946!). The exhibition has stories of parents writing in and telling how their children thought the book was a real-live animal – one preschooler tried to feed the book and another child gave it as a present to her cat!

But getting back to “Goodnight Moon”, the guide told us a fascinating story about a parent who read the story to her young son before he went to bed but then later she heard him crying and walked in to find him sitting on the bed with the book open and a foot on each page. The little boy loved the story so much that he was trying to climb into the room and was upset because he couldn’t get inside. I thought it epitomised the idea that children do not make the same distinctions as we do between fiction and reality – they are one and the same. Another story illustrating the same thing is the book “Little Fur Family” by Margaret Wise Brown. The author was so well known and established that she managed to convince the publisher to cover her book in real rabbit fur (this was 1946!). The exhibition has stories of parents writing in and telling how their children thought the book was a real-live animal – one preschooler tried to feed the book and another child gave it as a present to her cat! This caused an uproar in the South of of the US where segregationists tried to get the book banned. In the end it was put in a special reserve section of the library. See this quote on the issue:

This caused an uproar in the South of of the US where segregationists tried to get the book banned. In the end it was put in a special reserve section of the library. See this quote on the issue: