The aim of the Q&A series is to get an inside look into some of South Africa’s leading education academics, policy-makers and activists. This is the twenty-third interview in the series. Carole Bloch is Director of PRAESA.

(1) Why did you decide to go into education?

As a student, I taught guitar to children, then music appreciation to preschool children. I loved this experience and found that I connected really well with little children and was fascinated by their imaginations and the way they played and thought. After my BA at UCT, it was really luck that I got to do a PGCE in the UK… a long story, but I never looked back. I loved teaching, first teens with literacy learning problems, later preschoolers who played voraciously, with everything they could get their hands on. I experienced first-hand how to facilitate reading and writing as a personally meaningful, emergent process… I’ve been a teacher, and a learner in literacy education ever since.

(2) What does your average week look like?

I am a bit of an octopus these days – I have tentacles waving about in all directions with Nal’ibali. Keeping a national campaign moving along means having an overall vision at the same time as you are involved in details. There is ongoing networking and fund raising, overseeing and informing the literacy and literary information we put out across platforms, training and mentoring programmes and of course troubleshooting technical challenges, like newspaper supplements not arriving where they should on time and supporting colleagues, dealing with payments and staffing issues. Then there is always the daily email deluge! We communicate with great rapidity which means things can happen quickly, but I sometimes feel quite alarmed by the sheer volume of messages that come my way! The evenings and early mornings are often times to catch up with reading and trying clear my head to write.

(3) While I’m sure you’ve read many books and articles in your career, if you had to pick one or two that have been especially influential for you which one or two would they be and why?

It’s hard to choose just one or two: Illich Chukovsky’s 1960 classic From 2 to 5 on the extraordinary linguistic genius of young children and all of Vivian Paley’s books, especially The Boy who would be a Helicopter on the enormous literacy learning and general educative power of imaginative play and stories and Stephen Krashen’s Power of Reading from the 1990s which summarises the research on free voluntary reading (see http://www.sdkrashen.com/).

(4) Who do you think are the current two or three most influential/eminent thinkers in your field and why?

There are so many. Quite a few I don’t agree with, so I won’t mention them! For me, social anthropologist, Barbara Rogoff ‘s work on children participating as cultural apprentices in communities of (reading and writing) practice is really useful when thinking about what we need to understand about how reading culture development takes place. It fit’s amazingly well with the New Literacy Studies – Brian Street and David Barton et al’s conceptions of literacy as social practice – what I like especially about her is that she makes clear that people both join communities of practice and change them by their participation, such a critical insight for South African environments (eg Rogoff 1991, 2005).

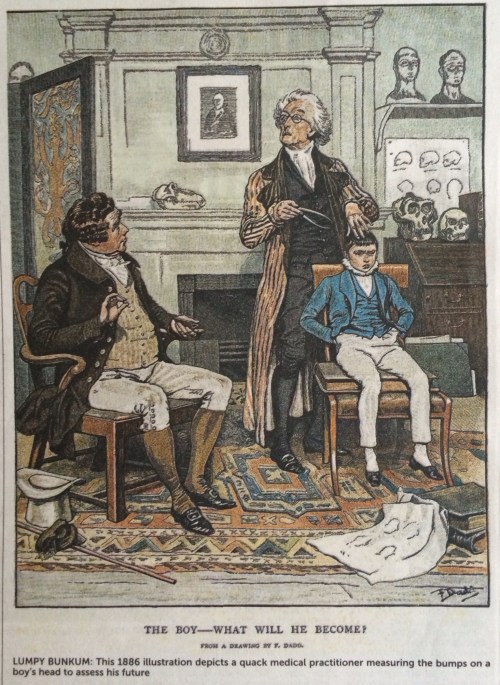

Kenneth Goodman, though sadly much vilified I think is one of the greatest thinkers about the reading process – it is in many ways really anticipating some of the recent insights from brain research – about how the senses work in general such as Chris Frith’s fascinating 2007 book Making up the Mind, on how the brain predicts (Goodman said that “reading is a psycholinguistic guessing game” (see eg Goodman, 1967). His work also helps us to understand that the process underlying reading is the same in any language (research with languages very different from English, like Chinese shows this), and so we don’t have to get bogged down worrying about that in literacy teaching with little children. There’s a really interesting article by him and others too which contests some of the neuroscientifc claims about how children read put forward by phonics proponents like Sally Shaywitz (see http://ericpaulson.wp.txstate.edu/files/2014/05/strauss_goodman_paulson_2009.pdf). I think there is so much differing ‘evidence’ that refers to teaching reading by experts in diverse fields, like linguistics, (who often tend to like to dissect languages and think when you learn to read you have to do this too) and also neuroscientists who do not necessarily understand how little children learn to read (eg Stanislas De Haene 2009). These can influence policy and have negative effects on the lives of young children – I mention some of this later.

5) What do you think is the most under-researched area in South African education?

Understanding the way babies and young children learn to speak, read and write in multilingual settings.

6) What is the best academic advice you’ve been given?

I think two pieces of advice have stood out for me over the years – the one was from Neville Alexander who I worked closely with for two decades. In the days when very few people were working on ‘alternative’ approaches to young children’s literacy teaching, I sometimes would feel despondent when my ideas and approach seemed to fall on unresponsive ears. Neville used say “Don’t worry about what other people say or think – you know what you are doing, just get on with it”. I realised how significant a) support and b) conviction are to push on and keep going. Another person who helped me with a wise comment which I’ve never forgotten was Elsa Auerbach, an adult literacy specialist from Boston, who’s classic article also influenced me many years ago: http://linksprogram.gmu.edu/tutorcorner/NCLC495Readings/Auerbach-Sociocontemp_familyLit.pdf). When I asked Elsa how she would help teachers and teacher educators to deepen their literacy knowledge and understandings, given the huge disparities in education we were trying to address, she said to me very simply, that we all need the same kind of opportunities– in a nutshell to read, reflect and experience many demonstrations of good practice. This simple insight has guided me for many years as I’ve mentored others.

7) You are currently the director of PRAESA and involved with Nali’bali, for those that are unfamiliar with these organizations can you give an overview of their aims and approach and maybe some of your/their plans for the future?

PRAESA from its beginnings in 1992 was an NGO based at UCT involved in multilingual education, research, training and materials development – essentially to help transform children’s educational opportunities using the foundation of mother tongue based bilingualism. Our research and all development work has been embedded in the view that a home language or languages should be the bedrock for learning, used to deepen thinking and conceptual understanding (see www.praesa.org.za). Other languages can be learned and added to a child’s linguistic repertoire, rather than being replacements. The longer the home language is used, the more support the child is actually getting. As many of us are aware, this mother tongue based education has not been implemented, except for in experimental ways, I believe to the extreme detriment of the educational opportunities for the majority of children.

In 2012, we initiated the Nal’ibali reading-for-enjoyment-campaign. This grew out of the previous twenty years of literacy research and practical work in multilingual settings which used stories and home languages for language and literacy teaching and learning. Because the story form is universal to all of us and integral to the way our minds work, the obvious route to literacy learning is to inspire a love of reading among all children. So Nal’ibali aims to nurture storytelling and reading for personal satisfaction, particularly in children, but also in the adults who are their role models and nurturers. Nal’ibali involves an ongoing collaborative effort with many partners to help put into place the conditions that support the initial and ongoing literacy development of all children irrespective of class, linguistic or cultural backgrounds. We’re doing this through mentoring, workshops and collaboration with communities, supporting reading clubs, literacy organisations and trying to elicit the support of volunteers of all ages, integrated with a media campaign and the development of multilingual literacy resources and stories. Our vision is a literate society that uses writing and reading in meaningful ways and where children and adults enjoy stories and books (and of course non-fiction too) together as part of daily life. The mission – and clearly we all need to be involved for this to happen – individuals, NGO’s, universities, government and business – is to create the conditions across South Africa that inspires and sustains reading-for-enjoyment practices (www.nalibali.org and facebook nalibaliSA).

8) You have been heavily involved in research on early literacy in African settings, can you give us an overview of what we know about early literacy in African settings and also what we don’t know?

I can only talk about my views as to what I think we know and don’t know or somehow don’t acknowledge or value …

In a nutshell, we know that most children, irrespective of class, socio-cultural and linguistic background are capable of becoming competent, avid and creative readers and writers but that huge numbers of mainly African language speaking children don’t – and that the conditions that need to be in place for successful learning to take place are mainly in place for children of the elite only. We know that a combination of factors is involved and that these cut across home, community and school. But we don’t seem to widely appreciate the incredible importance of the ‘invisible’ literacy learning that takes place in the daily, informal community and home language ‘goings on’ of literate homes, and what it means when such learning, for whatever reasons, cannot take place.

We know that teachers ‘bring with them’ like children do, their literacy theories and practices into the classroom, and that a real stumbling block in the early years is how we still tend to train teachers to view their task as teaching skills as a priority over demonstrating and making possible the use of written language for personally meaningful reasons (This contributes to the learn to read/read to learn myth). We should know that this blocks many children off from highly effective learning strategies that could reveal them as exuberant emergent readers and writers that we expect from most young English speaking children. We don’t widely acknowledge, and maybe we don’t know, that the consequence is a cyclical one of adults tending to underestimate poor children’s capabilities in formal education situations, believing the children are struggling with ‘the basics’, when actually the struggle is that the basics of written language are being denied them!

We know that the push down from higher education is exacerbating this through the justification of curricula that package skills and knowledge in ways that override considerations about how to motivate young children ‘s enormous learning capacity. Global forces push down too – a current example is an assessment packages like EGRA, which grew from the USA ‘s DIBELS, that has caused so much heartache and stress for so many families (see The Truth About Dibels, Goodman 2006).

We know that low status and use of African languages for print functions (including the dearth of fiction and non fiction) means fewer adults are leisure readers. But we don’t widely value or address the fact that it seems extremely difficult to teach others to read when you don’t have your own repository of knowledge and stories arising from the texts you’ve read over time, to draw from – with the overwhelming effect of poor reading habits being that you tend not to have what it takes to reap the benefits from and pass on a passion for knowledge and story to others.

Given what we do know, we don’t know why government (with support from business) seems unable to invest with unflinching determination in the translation of desirable world texts, including ones from Africa, to support African publishers to produce a steady flow of the books we need and order these to stock community and school libraries …. to inspire reading and creative writing among adults and children in African languages and English and also to use in the training and mentoring of adults to grow to know and manage these collections. We also don’t know why there is an insistence on making teaching so very hard for teachers and learning difficult for the majority of children living in South Africa after grade 3 by forcing teaching in a language often not known well enough to use with dignity and depth.

9) If you ended up sitting next to the Minister of Education on a plane and she asked you what you think are the three biggest challenges facing South African education today, what would you say?

The first is the fact that it is a tragedy that we haven’t implemented our Language in Education Policy of 1997, but that it is not too late and that this needs leadership from government and lots of information – in fact a campaign – to allow parents the opportunity to appreciate the issues involved in educating their children from a language perspective – how they would come to realise that they do not need to choose between English or African languages but that both are possible, and desirable.

The second is related and I’ve raised already – that government needs to act on the fact that until publishing in African languages is supported in a serious way, so that these languages are used in print for high status functions, including literature – and more of our adult population starts reading regularly for personal satisfaction and for pleasure, many children won’t become readers and writers in the fullest sense.

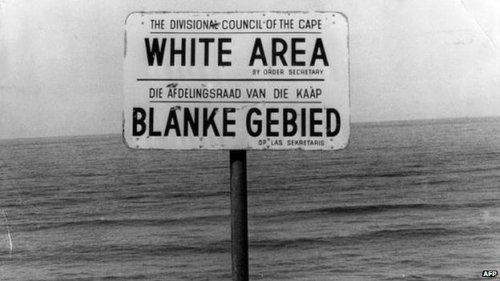

The third, if she was still listening, would be to discuss how to use literature to find practical ways to create a different ethos among us – one that promotes and encourages empathy and respect for each adult and child living in South Africa irrespective of background. We’d gather people together to generate a curriculum of shared stories for children of all ages, from South Africa, Africa and the rest of the world, which reflect the highs and lows of humanity – to support the growth of a new generation of people who reject stereotyping and prejudice, and value what we share in common, as well as our differences.

10) If you weren’t in education what do you think you would be doing?

I’d be a professional gardener as I love growing things, or I’d be a cellist.

11) What is the most rewarding and most frustrating thing about your job?

The most rewarding thing is seeing partnerships grow that are allowing so many people across South Africa to get involved in quite relaxed ways to enjoy the substance of reading: Seeing how my colleagues inspire others is humbling. Watching how interest in books grow in people of all ages when they are motivated. Seeing sceptical and weary-looking adults put on their playful hats to communicate with children and share stories in animated ways – this is stunning for me.

Frustrations are around how hard it can be to convince others that sometimes the most simple seeming solutions are the most profound sometimes… and of course the time it takes to get things done, mainly because we just don’t have the capacity, either human or financial – and knowing how much more SA industry and government could do to help us change the desperate situation we face in literacy education.

12) Technology in education going forward – are you a fan or a sceptic and why?

Total fan and total sceptic! I’m a fan of making the most use of technology. In Nal’ibali, for example, we offer a growing repository of free multilingual stories and guidance etc. on web, mobi and cellphone for adults to use with children of all ages. I think that the freedom it allows to create multilingually is extraordinarily powerful and I love the potential and sometimes actual freedom to share material without the rigid constraints of traditional publishing. But I’m a sceptic about the wisdom of proclaiming paperless learning. I don’t believe we should attempt to create an either-or situation. Particularly, but by no means only – for babies and young children we still want print on paper and books. I think we need to support and nurture our publishing industry more now than ever before.

13) If you were given a R15million research grant (and complete discretion on how to spend it) what would you use it for?

I’d facilitate a major qualitative research process on various aspects of Nal’ibali: I’d like to track groups of children living in different settings from home to reading club to school over a period; document the indicators of the effects of reading for enjoyment on motivation, engagement and achievement, literacy and school learning, family dynamics etc. I know that our only glimmer of hope to persuade policy makers, linguists and many involved in education that what we are doing is essential is ‘scientific’ evidence!

//

Some of the others on my “to-interview” list include Veronica McKay, Thabo Mabogoane, Maurita-Glynn Weissenberg, Shelley O’Carroll, Yael Shalem, Linda Richter and Volker Wedekind. If you have any other suggestions drop me a mail and I’ll see what I can do.

Previous participants (with links to their Q&A’s) include, Johan Muller, Ursula Hoadley, Stephen Taylor, Servaas van der Berg, Elizabeth Henning, Brahm Fleisch, Mary Metcalfe, Martin Gustafsson, Eric Atmore, Doron Isaacs, Joy Oliver, Hamsa Venkat, Linda Biersteker, Jonathan Clarke, Michael Myburgh, Percy Moleke , Wayne Hugo, Lilli Pretorius, Paula Ensor, Carol Macdonald, Jill Adler and Andrew Einhorn.