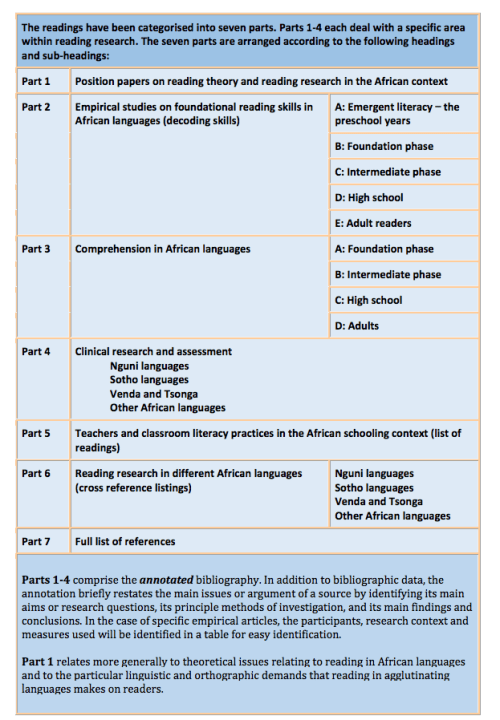

These are some things I’ve been reading and listening to over the last while. Sharing is caring 🙂 Post yours in the comments below…

- “Bread and roses” – political slogan and poem – sung by The Radcliffe Pitches (thanks Brett!). The phrase “Give us bread but give us roses too” resonated with me as the most succinct way of expressing that the fight for dignity is about more than meeting basic needs.

- Linked to the above poem, I really enjoyed Joel Modiri’s article “The Law’s Poverty” and the clash between an a-historical human-rights approach to the law and a historically-situated “justice” approach to the law.

- “To be or not to be” – Masha Gessen on choice, Jewishness, identity, emigration and America (thanks again Brett!)

- STARI – Excellent resources on reading in Middle School (Grade 6-8). The STARI project run by Catherine Snow –

- WordGen – More resources on developing vocabulary through a 72-week discussion program (Catherine Snow’s baby)

- Huapango – a Mexican folklore ballet showcasing the incredible cultural variety and richness of the Mexican peoples. Each part of the song was created with a one group in mind and the ballet showcases their traditional dances and outfits. I’ve been listening to this on repeat for about a month (Thanks Victor!)

- Jonathan Jansen’s address to the Stanford Senate: “The case for the Academic Senate” – I include an excerpt from that address below:

“What does this say about the role of the Senate? Quite simply, the question of knowledge is at its root a question of agenda-setting in any Senate. This points to leadership, of the President and in particular of the Senate executive. A university Senate has a choice. It can be primarily a place of administrative regulations, rules and procedures but it can also be an arena in which the “big questions” of academy and society come to enjoy prominence on the Agenda. I wish to suggest five such big questions (the first already referenced earlier) that should constitute a major part of the agenda of Academic Senates concerned with the purposes of a university in the 21st century:

(1) The representational contents of the curriculum (what we teach)

It matters enormously that Senates step back on a regular basis and ask questions about knowledge, identity and curriculum. What knowledge matters in the 21st century? Whose knowledge “makes it” into the curriculum? And is the Stanford graduate in any field of study equipped to encounter and act on a complex (integrated and divided) world?

(2) The complexion of the professoriate (who teaches)

It does matter that a Senate asks questions of who teaches. The strength of the best universities in the world depends crucially on the recruitment of the best talent across contexts, cultures and countries. It also conveys to students (and faculty) a crucial point that advanced knowledge is not locked up in one race, gender or culture.

(3) The diversity of the undergraduate (and also graduate) enrolments (whom we teach)

It matters that a Senate keeps returning to the question of who the student is we are privileged to teach. All students benefit from the knowledge that comes with learning from and alongside students from different class, race and ethnic backgrounds but also from other countries. (It always puzzles me that a university can boast, for the purposes of improved rankings, about the exclusivity of its entering first year class). It is also true that the strength of Stanford’s academic programs has always depended on the recruitment of the most talented graduate students on the planet.

(4) The methods of teaching (how we teach)

It is difficult to imagine a Senate in the heart of the Silicon Valley not returning to the agenda the question of the best technologies (in the broadest sense of the word) for teaching in this century. I know Stanford does this well. And yet efficacious teaching is about much more than technology-led instruction or teaching innovations in the classroom; it is about powerful teaching that engages student minds, develops criticality, stirs social and intellectual discomfort, and prepares those who seek learning to become comfortable with uncertainty. In short, how does the Stanford Senate account for teaching in this large and complex institution?

(5) The impacts on learning (whether teaching matters)

An academic Senate agenda should be concerned with the question whether what we teach matters in the lives of students. Powerful teaching is only evident in powerful learning. But this has to be assessed beyond the limiting confines of passing or failing in modules, courses or even degrees. Such assessment asks questions about the enduring effects of the educational experience beyond marketing anecdotes or even “feedback loops” from the corporate environment. Do graduates from this great university do much more than earn a living on a well-paid job? That surely must be among the broader purposes of a Stanford education and, therefore, a concern of the Senate.”

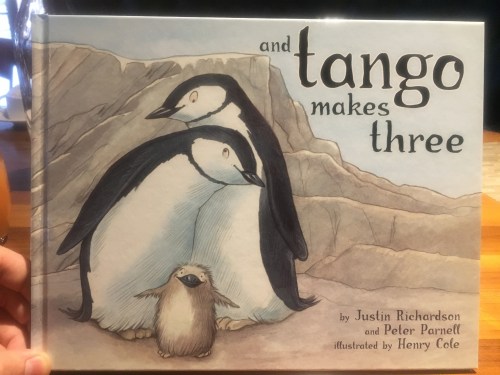

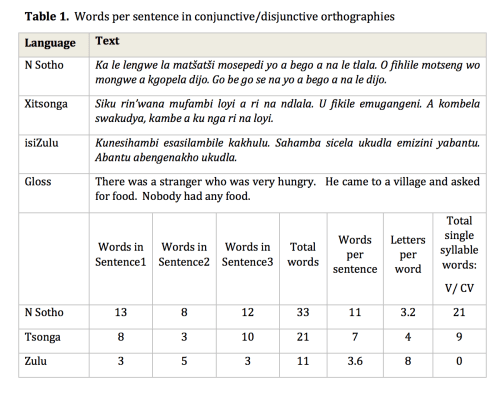

So in isiZulu the first sentence is only 3 words while in Northern Sotho (Sepedi) it’s 13 words. We go on to show that there are also large differences in ‘required fluency’ across these languages and that accuracy rates and speed differ between conjunctive and disjunctive languages – see below.

So in isiZulu the first sentence is only 3 words while in Northern Sotho (Sepedi) it’s 13 words. We go on to show that there are also large differences in ‘required fluency’ across these languages and that accuracy rates and speed differ between conjunctive and disjunctive languages – see below.

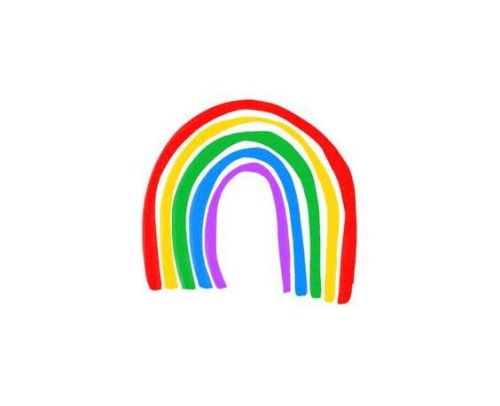

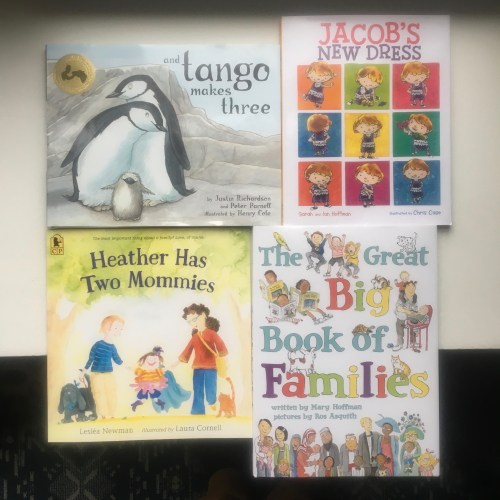

Juno Dawson –

Juno Dawson –

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people.

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people. Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.

Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.