I recently had the privilege of visiting the incredible Vancouver Public Library for a few hours on Sunday morning and was totally blown away (thanks Kelsey for recommending it!). I was at the CIES education conference in town during the week and in hindsight I wish I had just spent it talking to the librarians instead, documenting what, how and why they do what they do. As it turns out, while I was wandering the floors of the library I was actually in the process of missing my flight home! In the end I had to book a series of one-way flights home which turned into a long (52-hours!) and expensive journey back to Cape Town. Nevertheless, I probably wouldn’t have had time to visit VPL had I not missed my flight. C’est la vie.

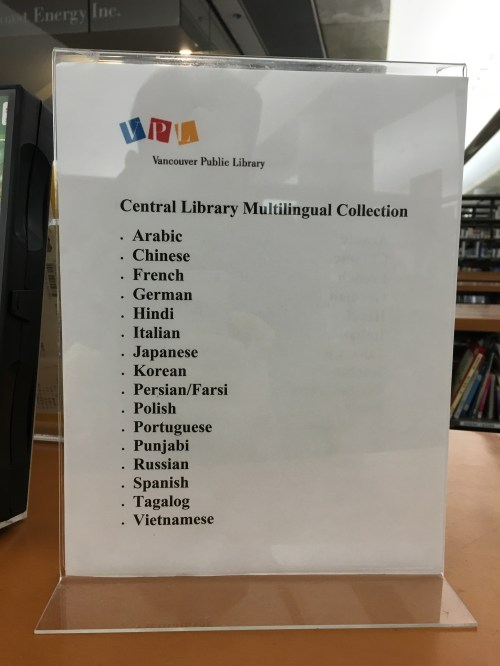

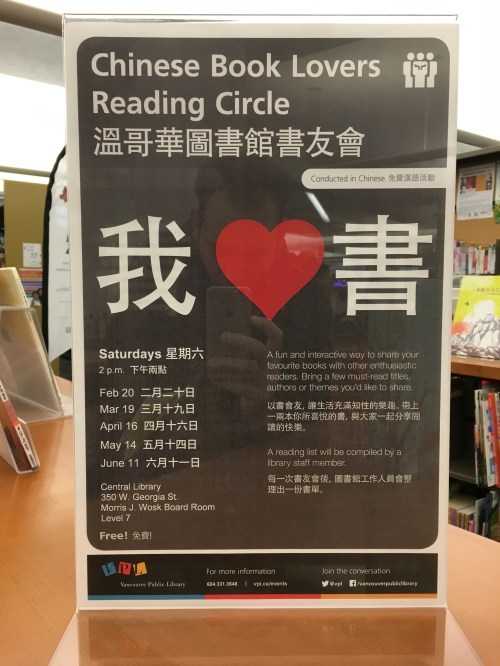

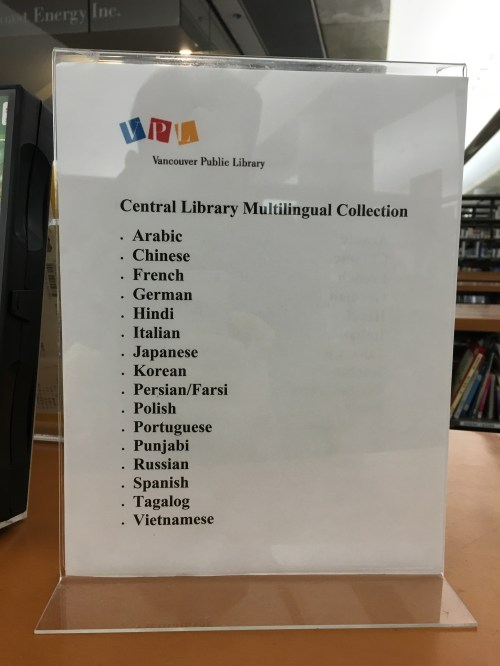

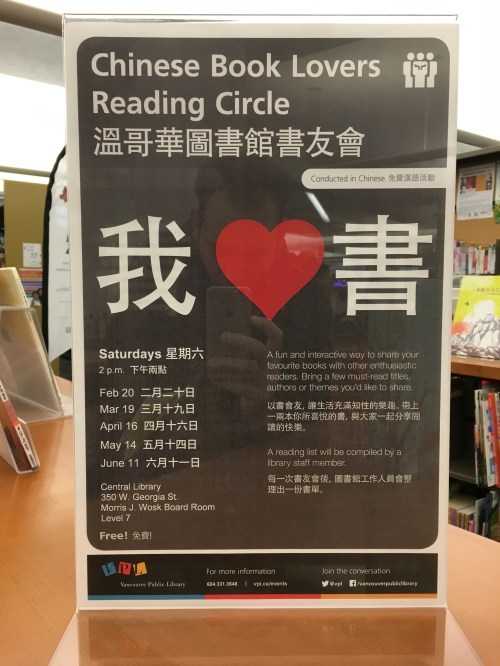

If I’m honest I found parts of my VPL experience a little emotionally overwhelming. I don’t think this was because of the library itself but rather because of the Canadian values and philosophy that it embodied. Walking around Vancouver and seeing various public announcements all in multiple languages was mirrored at VPL where half of an entire floor was dedicated to books published in other languages.

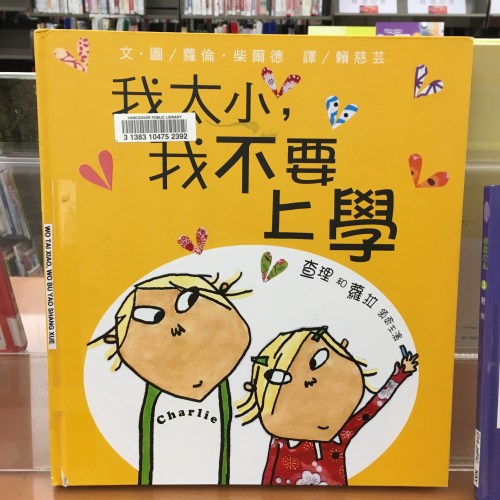

There were also some children’s books in other languages but not nearly as many (or as diverse) as in the adult books section.

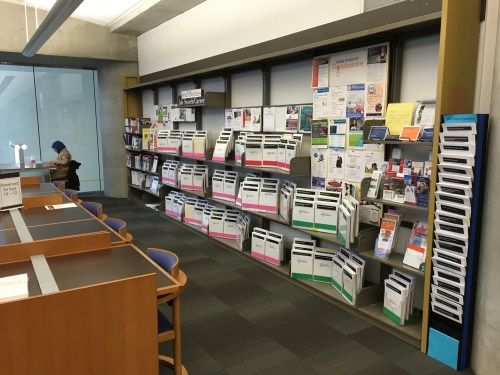

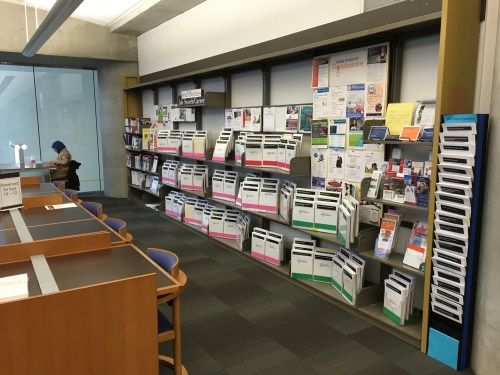

The part that I found quite emotional was the “VPL Skilled Immigration Information Centre” which helps newly resident skilled immigrants find work. They have created 8-10 page booklets on each career with information on things like starting salaries, industry websites, and who the large employers are in that field. In the handbook on ECD practitioners there was even a section on “hidden jobs” and how to access these (jobs that aren’t advertised anywhere!).

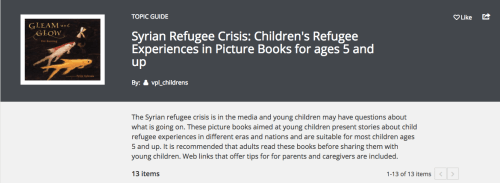

Like many people I have been following the US presidential nominations and the contrast between the Canadian and American responses to the Syrian refugee crisis are just worlds apart. America has agreed to welcome 10,000 Syrian refugees while Canada is taking in 25,000 Syrian refugees (Note: American population: 319 million, Canadian population: 35 million). But for me it actually wasn’t about the numbers it was about the tone and the attitude towards refugees (and diversity in general). This was one of the posters in the library:

The day before I was taking the bus to the Capilano Suspension Bridge Park and saw a photo of a Syrian girl on the side of the bus with an explanation that the government of Canada would match dollar-for-dollar any donation Canadians made to charities supporting the Syrian refugees (Red Cross, UNICEF, Save the Children etc.), and that this was up to $100 million. Once at Capilano I was also encouraged by the way that the official guides spoke of the traditions and knowledge of the First Nations people. As we walked around the park the guides told us why the First Nation’s people named certain trees the way they did and about their cultural traditions and practices. At no point did I feel that they were being exoticised or belittled. Their insights and names were woven into the park’s signs and boards and included in the children’s treasure/science hunt maps.

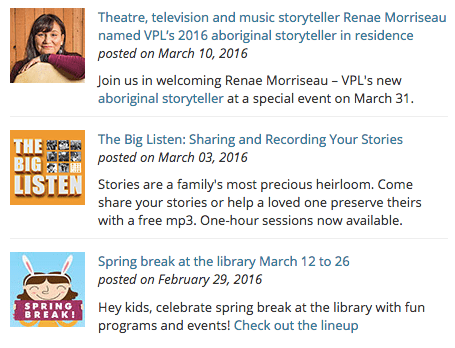

Back to the library, this disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

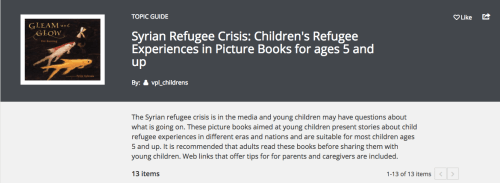

Throughout the library there were references to Syria and the refugee crisis with materials, both for Canadians and Syrians. In the children’s section there was even a list of picture books about refugees from other countries to help children understand what was going on.

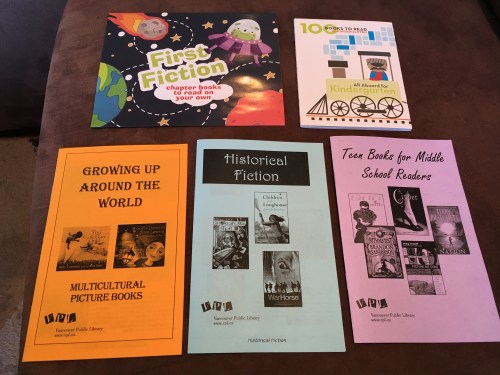

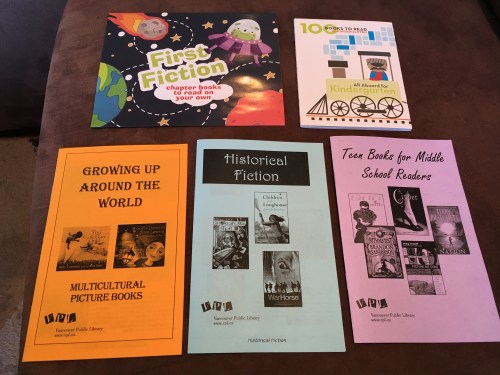

I was so impressed by the work that the children’s librarians had done. There were curated reading lists for different age groups and different topics with brief explanations of each book next to a picture of the front page. The front covers of each booklet are included below:

Forging the path of what a library looks like in the 21st century

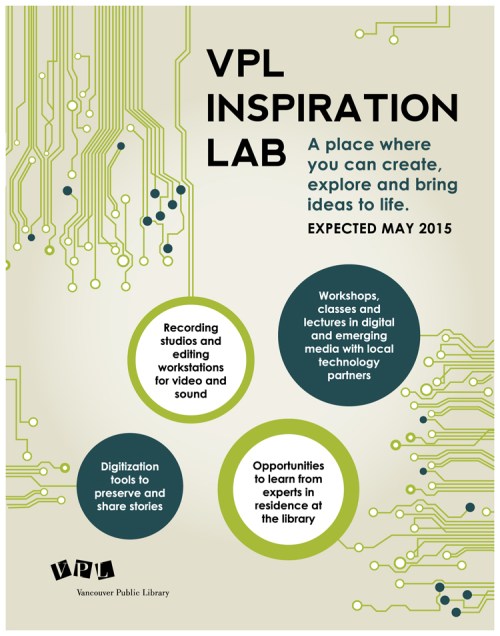

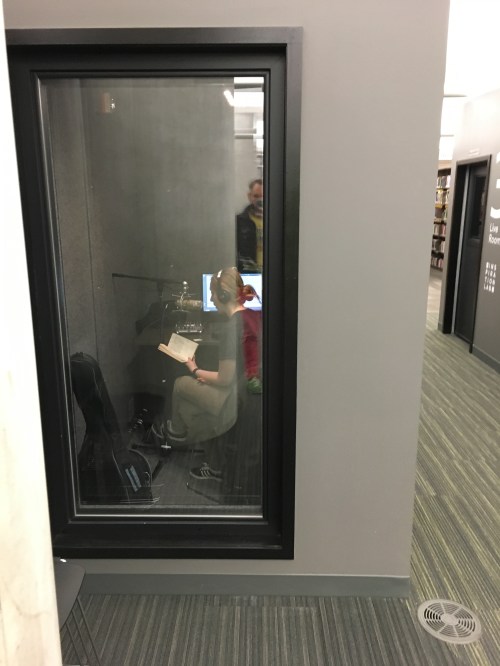

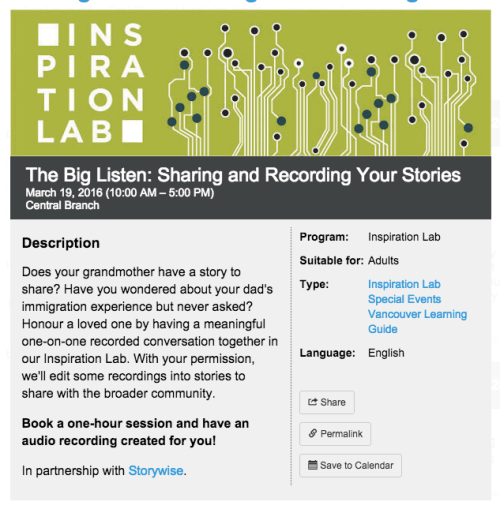

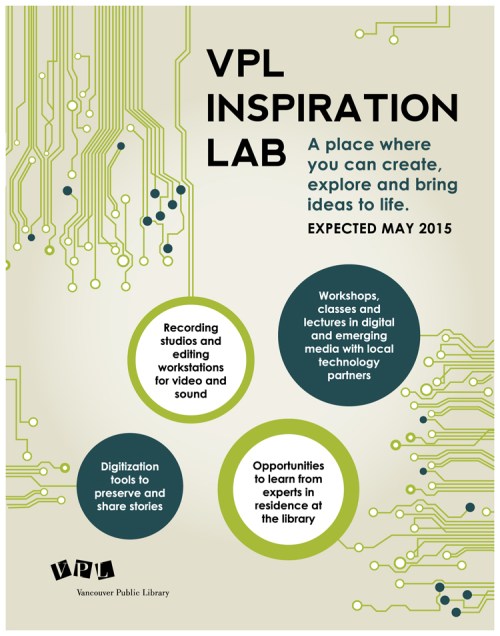

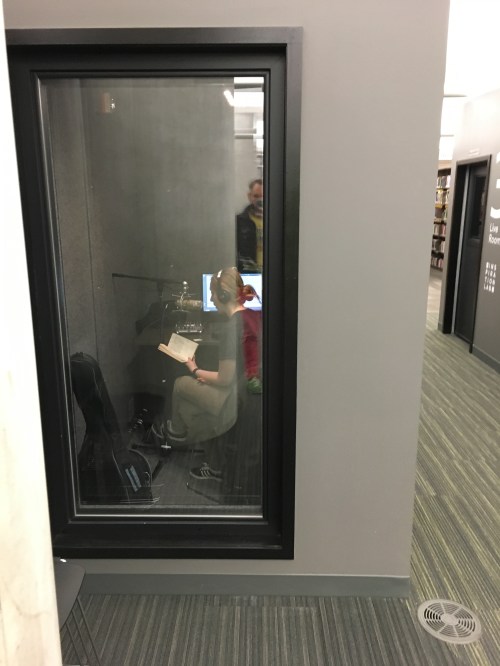

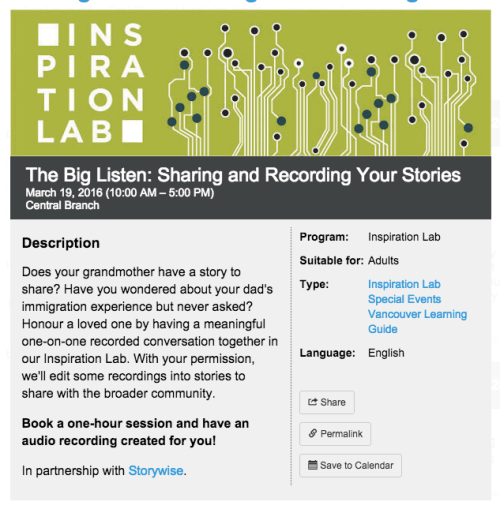

Another thing I was struck by was how modern and professional everything looked. Apart from things like couches, computers, wifi and art, I got the distinct sense that the library was trying to claim for itself a space in the digital age. At the VPL Inspiration Lab there were multiple recording rooms with specialist microphones and video-cameras, green-screens, conversion devices (digitising VHS, for example). And all of this was free. There were also pamphlets and courses on things like how to save a document, how to browse the internet, and how to use social media (presumably for the elderly).

In fact while I was walking around the Inspiration Lab I saw someone giving a talk to about 12 people on ISBN numbers and how to publish your own book, and someone recording their narration of a book…

And this is something that is explicitly encouraged and facilitated by the library:

Since coming home and reading their Annual Report I quickly realised that the VPL is not the norm, either in Canada or in the OECD countries, and certainly not in South Africa. The Vancouver Public Library was ranked the best library in the world in one study. Now obviously these rankings (like all rankings) are a little dodgy, but the point is that this is one of the top libraries in the world.

My thoughts about VPL have been sloshing around in my brain for a week now and I’ve started realising a number of things about myself and public versus private goods. Growing up I think we did visit the public library a few times but it wasn’t anything spectacular or interesting. I never developed a love of public libraries or fully appreciated the role they could play in providing a social commons where books, information and knowledge were the principal means of engagement and interaction. Rather they were low-budget cranky places with old books and old people. Instead I developed a love of book-shops and book ownership. I think this was because walking around a good book shop felt welcoming and interesting; it has new books, has displays, has events (book launches, readings, discussions), it doesn’t feel grimy. But this is only because I can afford to buy the books that I like. And so here I start to see in my own life one small example of the way that the South African cogs work to perpetuate an unequal system. I don’t use a public library because they are of low quality, I buy books instead. So I never see the value of funding and using a great public library (at least until now). So here we are with thousands of wealthy people with small private libraries essentially each creating their own space that could otherwise be collectively provided by a great public library (and with public funds), which could then also be used by everyone.

I’m sure you can see that it’s not difficult to find the parallels between this and the private provision of healthcare, schooling, legal services, recreational facilities etc as compared to the public provision of these services. So it feels like we’re in a low-level equilibrium where the rich in SA can afford to fund for themselves whatever they need without any recourse to their tax money, and the poor are forced to accept whatever the government provides. This explains why many tax-payers (at least the South African tax-payers I know) see their tax as a kind of fee where you pay it with little expectation of return or service.

It costs a lot of money to fund and operate the 22 libraries that make up the Vancouver Public Library system, R527 million to be exact. Yet 94% of Vancouver residents support the use of tax dollars to fund the VPL.

If I had to say, I do not think that we can simply say “the first step is that the libraries that we do have need to better serve the communities within which they are situated.” while of course that is true, the apartheid legacy means that there are very few well-resourced libraries in the poorest areas (notably townships). I think it is an open question, and one that’s worth discussing, whether a functioning public library system that has the expertise and resources to support local residents (and especially local schools) is worth the considerable resources it would take to create such a system. The case needs to be made that (and in my view, is yet to be made) that it is possible to create such a library given our capacity and resource constraints. And secondly that it is a better use of resources than additional money on housing, child-support grants, teacher development etc.

I’m interested to hear your thoughts Equal Education, Nal’ibali, Bookery, Fundza, Bookdash and everyone in this space. Should we be funnelling millions of rands into creating functional public libraries in low-income high-density locations like Khayalitsha? Why aren’t we? Do we know how to do it? Who should lead the way?

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

Important new research article by Stephen Taylor and Marisa von Flintel (2016) titled “

Important new research article by Stephen Taylor and Marisa von Flintel (2016) titled “