Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.

Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.

Last night I finished a novel I’ve been reading for a few months on and off and cried into the sofa as I pored over the last few pages. “A Little Life” by Hanya Hanagihara was recommended to me (thanks James!) after we discovered a mutual love of “The Secret History” by Donna Tartt. A Little Life is a long book but one that is easy to slip into and feel a part of. It is a tragic story full of sadness and inhuman pain, but the relationships and the meaning sunk deep into my heart as I read on. I didn’t realise how attached I was getting to these fictional characters living non-existent lives in New York.

Before I had finished Hanagihara’s novel I came across Paul Kalanithi’s “When Breath Becomes Air” in an airport and bought it for the flight. I was absolutely hooked and read it in one day. The author, a Stanford neurosurgeon/neuroscientist, discovers that he has an aggressive cancer just at the point when he is meant to start reaping the rewards of 10-years of gruelling preparation. What do you do when you have 2 years left to live? For Kalanithi he turned to his other vocation – reading and writing.

“Lost in a featureless wasteland of my own mortality, and finding no traction in the reams of scientific studies, intracellular molecular pathways, and endless curves of survival statistics, I began reading literature again: Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward, B. S Johnson’s The Unfortunates, Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, Woolf, Kafka, Montaigne, Frost, Greville, memoirs of cancer patients – anything by anyone who had ever written about mortality. I was searching for a vocabulary with which to make sense of death, to find a way to begin defining myself and inching forward again” (p148).

I loved this book more than most others over the last few years. I found myself regularly reflecting on my own life as I read about his life and imminent death. Career choices, relationships, ambition, children, meaning, religion, mortality – he touches on everything and draws you in to the whirlwind that was his life growing up and now as it accelerates approaching death.

In a sense you can’t script a life like his. Before going into medicine he spent his youth obsessed with English literature and the meaning of life, giving him the lessons and existential resources our culture has found or created over the centuries. Science doesn’t comfort much in the face of death.

“A few years later, I hadn’t thought much more about a career but had nearly completed degrees in English literature and human biology. I was driven less by achievement than by trying to understand, in earnest: What makes human life meaningful? I still felt literature provided the best account of the life of the mind while neuroscience laid down the most elegant rules of the brain. Meaning, while a slippery concept, seemed inextricable from human relationships and moral values. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land resonated profoundly, relating meaninglessness and isolation, and the desperate quest for human connection. I found Eliot’s metaphors leaking into my own language. Other authors resonated as well. Nabokov, for his awareness of how our suffering can make us callous to the obvious suffering of another. Conrad, for his hypertuned sense of how miscommunication between people can so profoundly impact their lives. Literature not only illuminated another’s experience, it provided, I believed, the richest material for moral reflection. My brief forays into the formal ethics of analytic philosophy felt dry as a bone, missing the messiness and weight of real human life.

Throughout college, my monastic, scholarly study of human meaning would conflict with my urge to forge and strengthen the human relationships that formed that meaning. If the unexamined life was not worth living, was the unlived life worth examining?”

This last sentence hit me when I read it and hasn’t left me since. Am I really living my life?! I had recently come back from a Croatian island filled with compelling humans living such deliberate, authentic and vulnerable lives. Politicians, artists, nomads, hippies, techies, shamans – the works. Not all that glitters is gold – for sure – but there really were some golden folk there. We had endless conversations about desires, fears, comfort-zones, purpose and passion. And here I was living a fully defensible life.

“Him: When last did you really fail at something?”

“Me: Not recently”

“Him: Are you really trying then?”

“Me: I don’t know”

I realised how paralysed I was by fear and judgement. Of others, of my own. I’ve realised how incredibly critical I can be and that this has severe personal and social costs.

Kalanithi helped.

“Heading into my sophomore summer, I applied for two jobs: as an intern at the highly scientific Yerkes Primate Research Center, in Atlanta, and as a prep chef at Sierra Camp, a family vacation spot for Stanford alumni on the pristine shores of Fallen Leaf Lake, abutting the stark beauty of Desolation Wilderness in Eldorado National Forest. The camp’s literature promised, simply, the best summer of your life. I was surprised and flattered to be accepted. Yet I had just learned that macaques had a rudimentary form of culture, and I was eager to go to Yerkes and see what could be the natural origin of meaning itself. In other words, I could either study meaning or I could experience it. After delaying for as long as possible, I finally chose the camp.

…

Eventually the term ended and I was on the windy mountain road to the camp, still slightly worried that I’d made a wrong turn in life. My doubt, however, was short-lived. The camp delivered on its promise, concentrating all the idylls of youth: beauty manifest in lakes, mountains, people; richness in experience, conversation, friendships.

…

This was summer at Sierra Camp, perhaps no different from any other camp, but every day felt full of life, and of the relationships that give life meaning. Other nights found a group of us on the dining room deck, sipping whiskey with the assistant director of the camp, Mo, a Stanford alum taking a break from his English PhD, and discussing literature and the weighty matters of postadolescent life.

…

Back on campus, I didn’t miss the monkeys. Life felt rich and full, and over the next two years I kept at it, seeking a deeper understanding of a life of the mind. I studied literature and philosophy to understand what makes life meaningful, studied neuroscience and worked in a fMRI lab to understand how the brain could give rise to an organism capable of finding meaning in the world, and eniched my relationships with a circle of dear friends through various escapapades. We raided the school cafeteria dressed as Mongols; created a full fake fraternity, complete with fake rush-week events, in our co-op house; posed in front of the gates of Buckingham Palace in a gorilla suit; broke into Memorial Church at midnight to lie on our backs and listen to our voices echo in the apse; and so on. (Then I heard that Virgina Woolf once boarded a battleship dressed as Abyssinian royalty, and duly chastened, stopped boasting about our trivial pranks.”

I would recommend this book to anyone. I’m still processing what all this means for me and how I want to live my life. What and who I want to prioritise. Where I want to spend my energies. What I want to experience. Where I want to contribute. Who I want to be. Read this book.

“That which is only living. Can only die.” – T. S. Eliot.

Juno Dawson –

Juno Dawson –

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people.

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people. Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.

Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.

Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.

Recently things have been moving quite quickly in my life. Old projects are in full swing, new projects are gaining momentum and I’ve moved into a new apartment in Cape Town. (I even unpacked my books!) Somewhere in-between I travelled to Croatia and ended a long-term relationship. Today I didn’t go in to work.

Ahoy blog-followers and other readers on the intertrons! It’s been a while since I’ve updated my blog on what I’ve been doing since I got from the OECD in Paris. Things were a little up and down about where I wanted to live, where I was going to work and the longer-term plans for life. So some of that has been resolved and things are moving ahead swiftly. I’ve been appointed as a Senior Researcher at

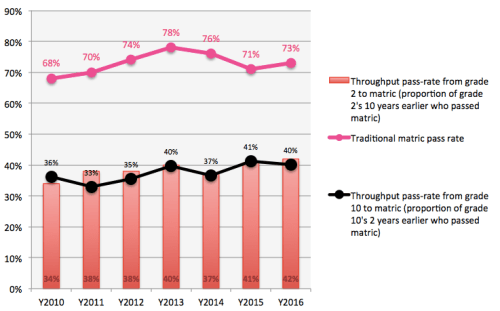

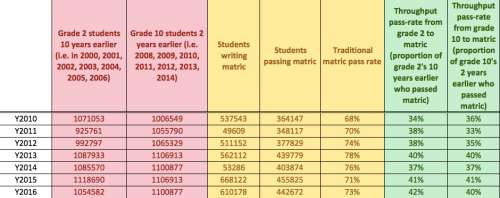

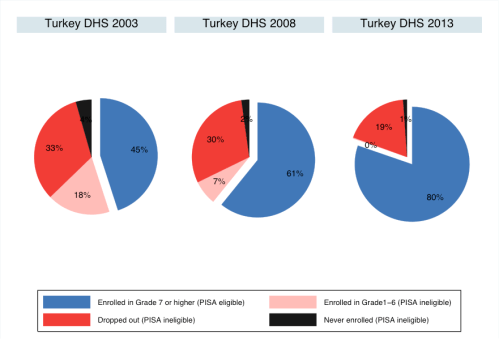

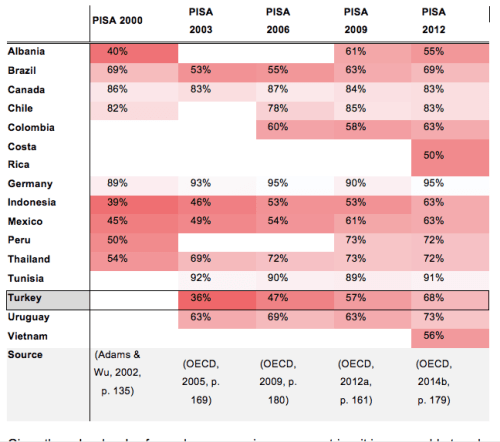

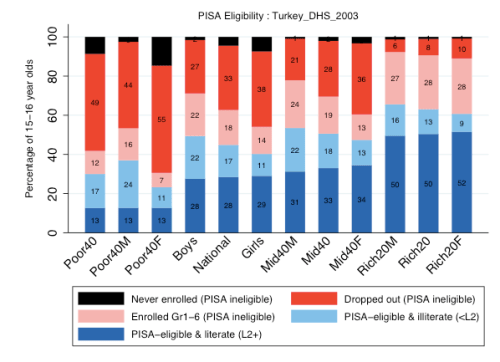

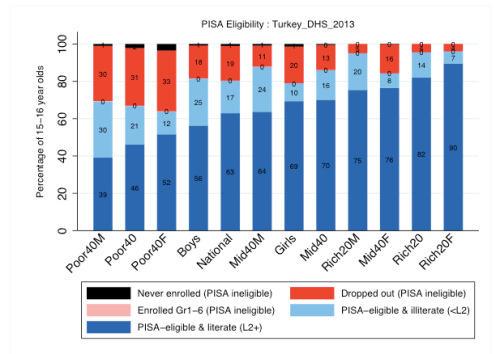

Ahoy blog-followers and other readers on the intertrons! It’s been a while since I’ve updated my blog on what I’ve been doing since I got from the OECD in Paris. Things were a little up and down about where I wanted to live, where I was going to work and the longer-term plans for life. So some of that has been resolved and things are moving ahead swiftly. I’ve been appointed as a Senior Researcher at  Of the OECD countries that participate in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Turkey has one of the lowest levels of performance and the highest rates of improvement in PISA scores. However, most analyses have traditionally ignored one vital question: what percentage of 15 year olds in Turkey are eligible for the PISA sample in each wave of PISA? A new OECD Working Paper focuses on this specific question and sheds new light on the performance of Turkey between 2003 and 2012. It shows that the percentage of students that were eligible for PISA in Turkey between 2003 and 2012 nearly doubled from 36% to 68% (using OECD indicators) or from 45% to 80% (using household survey data). This is summarised in Figure 1 below which provides information from the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of 2003, 2009 and 2012.

Of the OECD countries that participate in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Turkey has one of the lowest levels of performance and the highest rates of improvement in PISA scores. However, most analyses have traditionally ignored one vital question: what percentage of 15 year olds in Turkey are eligible for the PISA sample in each wave of PISA? A new OECD Working Paper focuses on this specific question and sheds new light on the performance of Turkey between 2003 and 2012. It shows that the percentage of students that were eligible for PISA in Turkey between 2003 and 2012 nearly doubled from 36% to 68% (using OECD indicators) or from 45% to 80% (using household survey data). This is summarised in Figure 1 below which provides information from the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of 2003, 2009 and 2012.

Yesterday

Yesterday