See below for a Q&A session I did for the Augest edition of “Lead the Change” run by the AERA SIG on Educational Change. PDF here.

See below for a Q&A session I did for the Augest edition of “Lead the Change” run by the AERA SIG on Educational Change. PDF here.

Posted in Education, Research, Uncategorized

Last week I spoke at the South African Librarian’s Conference at Highbury in KZN (presentation one and presentation two) and heard Barbara Band speak about how the library can be a vital tool to make schools more inclusive and help all students thrive. It struck a cord for me because in high school I basically lived in the library during breaks for three years. My librarians weren’t especially empathetic or insightful but it was still a safe place in an unsafe school. As always we can’t forget that South Africa is a deeply unequal country and that only 37% of learners are in a school with a library (Page 20 from this DBE report).

Last week I spoke at the South African Librarian’s Conference at Highbury in KZN (presentation one and presentation two) and heard Barbara Band speak about how the library can be a vital tool to make schools more inclusive and help all students thrive. It struck a cord for me because in high school I basically lived in the library during breaks for three years. My librarians weren’t especially empathetic or insightful but it was still a safe place in an unsafe school. As always we can’t forget that South Africa is a deeply unequal country and that only 37% of learners are in a school with a library (Page 20 from this DBE report).

In Barbara’s address she mentioned a bunch of different sites and resources and I asked her to email them to me so I could share the mall with you, so here they are:

Booklists and bookshops:

Juno Dawson – We Need Diverse Books

Juno Dawson – We Need Diverse Books

List of organisations that support diversity and inclusion:

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people.

IGLYO – International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Youth and Student Organisation: works with over 95 LGBTQ groups, run by and for young people. Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.

Metro – Equality and diversity charity, focusing mainly around London and South East.ALSO USEFUL:

Posted in Education, Gender, LGBT, LGBTQ, Links I liked..., Uncategorized

Below is a quick summary of what I was working on at the OECD in Paris last year. The full paper is now available online here:

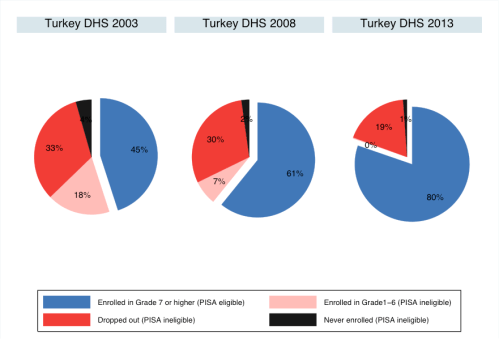

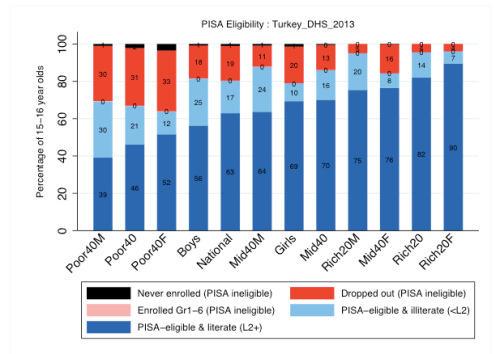

Of the OECD countries that participate in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Turkey has one of the lowest levels of performance and the highest rates of improvement in PISA scores. However, most analyses have traditionally ignored one vital question: what percentage of 15 year olds in Turkey are eligible for the PISA sample in each wave of PISA? A new OECD Working Paper focuses on this specific question and sheds new light on the performance of Turkey between 2003 and 2012. It shows that the percentage of students that were eligible for PISA in Turkey between 2003 and 2012 nearly doubled from 36% to 68% (using OECD indicators) or from 45% to 80% (using household survey data). This is summarised in Figure 1 below which provides information from the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of 2003, 2009 and 2012.

Of the OECD countries that participate in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Turkey has one of the lowest levels of performance and the highest rates of improvement in PISA scores. However, most analyses have traditionally ignored one vital question: what percentage of 15 year olds in Turkey are eligible for the PISA sample in each wave of PISA? A new OECD Working Paper focuses on this specific question and sheds new light on the performance of Turkey between 2003 and 2012. It shows that the percentage of students that were eligible for PISA in Turkey between 2003 and 2012 nearly doubled from 36% to 68% (using OECD indicators) or from 45% to 80% (using household survey data). This is summarised in Figure 1 below which provides information from the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of 2003, 2009 and 2012.

Figure 1: The educational status and PISA-eligibility of 15-16 year olds in Turkey in DHS 2003, DHS 2008 and DHS 2013

While PISA aims to assess a nationally representative sample of 15 year olds, because PISA is a school-based survey, in reality it excludes all students that are no longer in school (due to drop out or non-enrolment). PISA also only samples 15 year olds if they are in Grade 7 or higher. So PISA is really a nationally representative sample of 15 year old students that are still enrolled in school and are currently in Grade 7 or higher. This might sound like a trivial technicality, and in most wealthy OECD countries like Germany or Japan it is. But some OECD countries (like Turkey and Mexico) and many partner countries (like Vietnam and Indonesia) have high levels of student dropout and delay leading to low levels of PISA sample coverage. As an aside, the new PISA-for-Development initiative aims to also survey out-of-school 15 year olds in some of the developing countries participating in that programme.

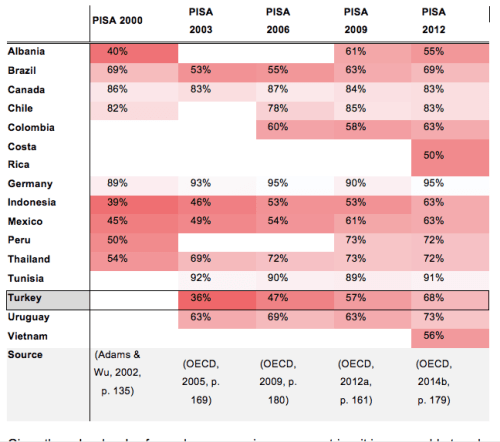

Since the beginning of PISA, the OECD has reported the percentage of 15 year olds that are actually eligible for PISA, what is called “Coverage Index 3*.” This statistic is calculated using census and enrolment data in each country and is provided in the overall PISA Reports and Technical Reports for all participating countries. For example, in Turkey in PISA 2003, only 36% of 15 year olds were eligible for PISA. That is to say that PISA 2003 in Turkey is only representative of 36% of the country’s 15 year olds. By comparison, the figure in Germany in 2003 was 93%. Table 1 below provides the Coverage Index 3 rates for a selected group of PISA countries with low levels of sample coverage (Germany and Canada are included as reference countries). From this we can see that a number of partner countries have very low levels of sample coverage, including Costa Rica, Indonesia, Peru and Vietnam, but also that some OECD countries (such as Brazil, Mexico and Turkey) have low levels of sample coverage.

Table 1: The percentage of the total 15 year old population covered by the PISA sampling frame (Coverage Index 3) in selected countries

Given these low levels of sample coverage in some countries, it is reasonable to ask: how would the results change if we included PISA-ineligible 15-year-olds in our calculations? This is the focus of a new working paper published this week, titled “Underestimating Progress and Inequality in Turkey (2003-2012): Using PISA and DHS to form a complete picture of access and quality”. The method and results are briefly summarised below.

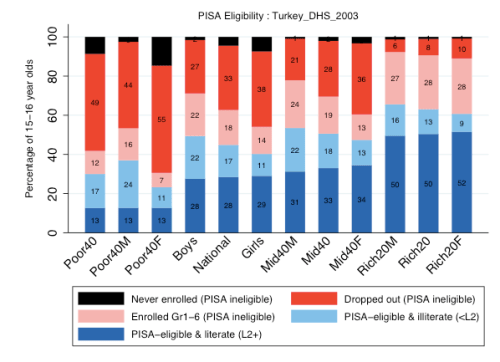

The paper applies a new method developed by Spaull & Taylor (2015) which aims to combine statistics on the learning outcomes of 15 year olds that are still in school (using PISA) with data on the number and type of 15 year olds that are not in school (using household-survey data). By assuming that PISA-ineligible students would not have reached PISA Level 2 in Reading and Mathematics – a relatively conservative assumption – we can calculate the percentage of the total population of 15 year olds that reach Level 2 in PISA, rather than only the percentage of those that are still in school. Figure 2 and Figure 3 below provide these breakdowns for Turkey in PISA 2003 and PISA 2012 respectively, and also by gender and socioeconomic subgroups. (Note: ‘Poor40’ means the poorest 40% of 15-16 year olds, and ‘Poor40F’ means poorest 40% of 15-16 year olds that are also female).

Figure 2 Access to Literacy (Level 2) in Turkey 2003 (PISA 2003 and DHS 2003)

Figure 3 Access to Literacy (Level 2) in Turkey 2012 (PISA 2012 and DHS 2013)

Note the results above will be different from those found in PISA reports because these results include PISA ineligible 15-16 year olds in the calculations.

The 7 main findings from the above are as follows:

Whether one chooses to use the Coverage Index 3 figures reported by the OECD itself, or those calculated from various DHS surveys, the conclusion is the same: there are large and changing proportions of Turkish students that do not make it into the PISA sampling frame and this has a substantial effect on the validity of inter-country and inter-temporal comparisons. This analysis shows that the gains in Turkey between 2003 and 2012 have actually been even more impressive than if one only looked at PISA data. This method could also usefully be applied to other middle-income and developing countries with high and changing percentages of PISA-eligible 15 and 16 year olds.

References

OECD. (2016). PISA for Development: Benefits for participating countries. PISA for Development Brief (Vol. 2). Paris.

Spaull, N., and Taylor, S., (2015). Access to what? Creating a composite measure of educational quantity and educational quality for 11 African countries. Comparative Education Review. Vol. 58, No. 1.

*There is an error in the Coverage Index 3 values provided in the PISA 2003 Report. The correct Coverage Index 3 values for 2003 can be found in the PISA Technical Report for 2003. See the Working Paper for a full discussion.

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

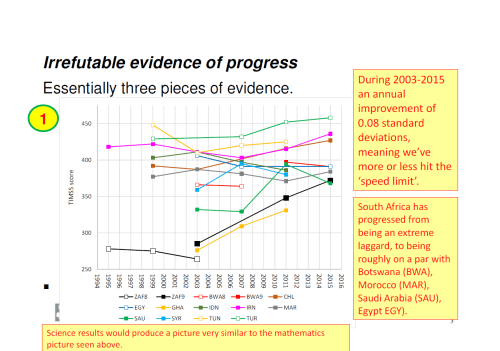

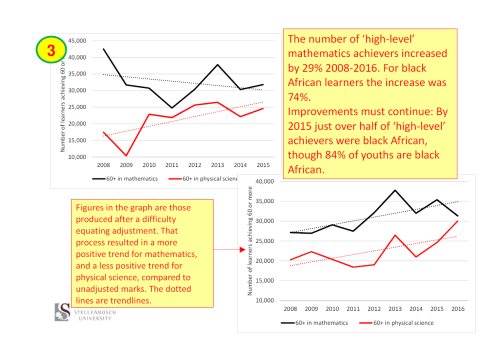

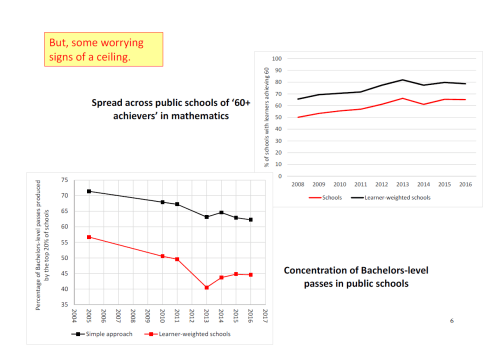

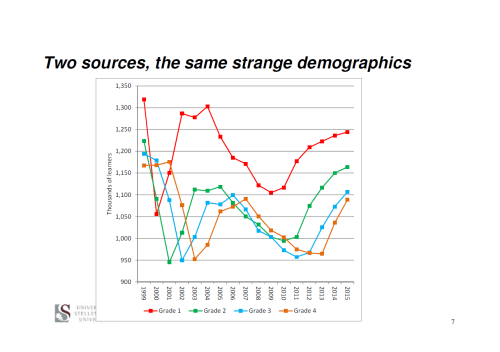

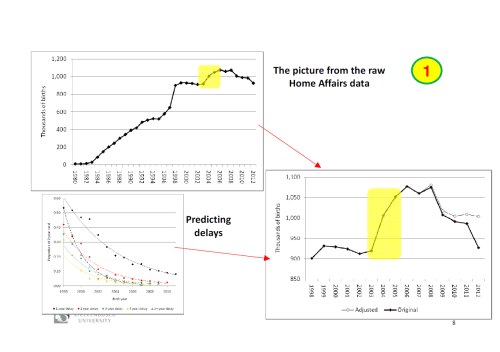

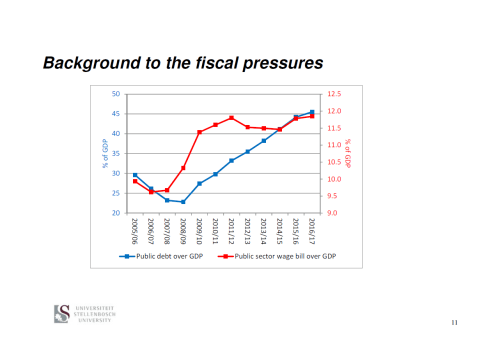

Yesterday RESEP had our first internal education workshop of the year and it was a great success. One of the presentations was by Martin Gustafsson on various trends and shocks in the education system. I found it to be especially important and interesting and asked if I could include the presentation in blog format, which Martin kindly agreed to (see below). For those that don’t know Martin he is easily one of the top 3 most knowledgeable people about the SA education system.

Yesterday RESEP had our first internal education workshop of the year and it was a great success. One of the presentations was by Martin Gustafsson on various trends and shocks in the education system. I found it to be especially important and interesting and asked if I could include the presentation in blog format, which Martin kindly agreed to (see below). For those that don’t know Martin he is easily one of the top 3 most knowledgeable people about the SA education system.

The 2 main points that Martin makes are:

Regarding #2, from discussions with Martin, who has been involved in reviewing the 2013 SACMEQ results, it seems clear that the 2007 to 2013 SACMEQ trend has indeed been positive for South Africa, and about as large as one could expect (and roughly in line with what has been seen in TIMSS). But these positive trends are smaller than the extremely large improvements, which I’ve argued are implausible, seen in earlier preliminary SACMEQ results presented to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Basic Education in 2016. What the sector urgently needs is the finalising of the 2013 SACMEQ process and the release of official learner results for all SACMEQ countries.

The trends seen in #3 below are from this 2016 paper of Martin’s.

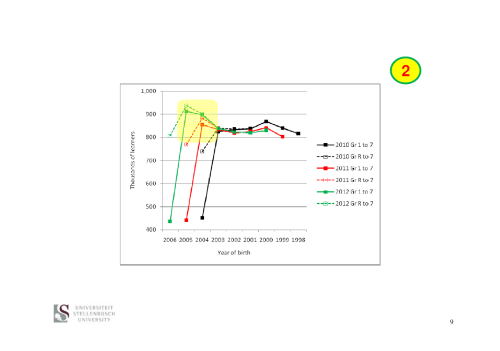

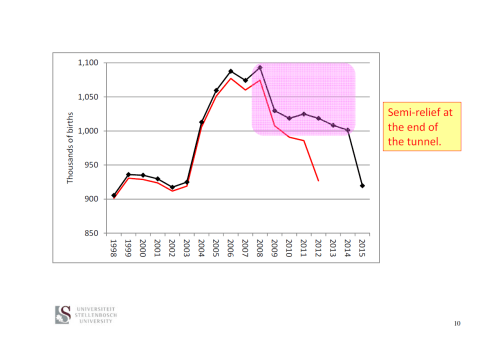

“At the lower primary level, what has clearly occurred is the entrance of a ‘wave’ of larger birth cohorts. In 2011, Grade 1 enrolments increased by 5.2% relative to 2010. In 2012, Grade 2 enrolments increased by 7.0%. By 2015, the increase had reached Grade 5, with enrolments in this grade increasing by 5.2% relative to 2014. As seen in Table 2 in the appendix, substantial increases were seen across all provinces, with the exception of Eastern Cape, which in fact saw a decline . The increases were strongest in Gauteng and Western Cape, almost certainly because these two provinces experienced a combination of two factors, both the demographic change in terms of larger birth cohorts, plus migration into these provinces. By 2015, grades 1 to 7 enrolments had reached 7,1 million in public ordinary schools, the highest figure since 2007 (when the enrolment total was also around 7.1 million). Moreover, total enrolment in just grades 1 to 5 was higher than it had been in any year since 2002. Projections indicate that the increases will continue to be felt in grades beyond Grade 5 in 2016 and beyond. ” Page 9 of this 2016 DBE Sector Report.

*Note in the graph s above (top left) the steady rise in births from 1982 to 1998 are simply because of better data-capturing rather than increased births. It stabilises from about 2000.

For those that haven’t read the DBE 2016 Sector Review I would strongly recommend doing so!

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

(The above article was published in the Mail & Guardian on the 6th of January 2016 and is available in PDF here).

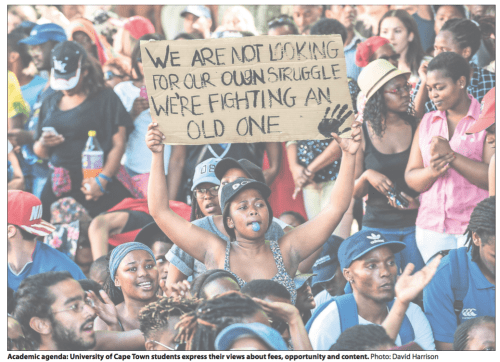

Students contest the status quo

Over the last two years, universities in South Africa have become increasingly contested spaces. Student movements like RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall have categorically rejected the status quo as unacceptable and are working to reorder not only the principles that govern universities, but ultimately the principles that govern the country. Of course the first order of business is challenging our current assumptions about who should go to university, what it should look like, and who should pay for it. And on all three fronts they have been phenomenally successful. It is really quite remarkable that a loose group of students who lack a political mandate, who have not been elected by anyone, and have virtually no resources have managed to achieve so much so quickly. They have brought whole universities to their knees and prompted the creation of a Presidential Task Team. Most significantly they garnered enough support to essentially force the government to allocate an additional R17 billion to higher education in the Medium Term Budget.

About 200 years ago, Napoleon Bonaparte famously quipped that a revolution is simply an idea which has found its bayonets. In the context of the various student movements I think it’s worthwhile to try and identify the underlying idea, its animating principle. As the student movements assemble and reassemble under different names (seemingly quite effortlessly), I think there is a leitmotif running through all of them; the unfinished business of 1994. There is a generation of young Black South Africans who feel that the terms of the negotiated settlement were unjust and let White South Africans off the hook. Dr Amos Wilson. a theoretical psychologist and social theorist, makes the logic behind this position explicit in the following quote:

“Justice requires not only the ceasing and desisting of injustice but also requires either punishment or reparation for injuries and damages inflicted for prior wrongdoing. The essence of justice is the redistribution of gains earned through the perpetration of injustice. If restitution is not made and reparations not instituted to compensate for prior injustices, those injustices are in effect rewarded. And the benefits such rewards conferred on the perpetrators of injustice will continue to “draw interest,” to be reinvested, and to be passed on to their children, who will use their inherited advantages to continue to exploit the children of the victims of the injustice of their ancestors. Consequently, injustice and inequality will be maintained across generations as will their deleterious social, economic, and political outcomes.”

Thinking that the various incarnations of the student movements are primarily about universities is a mistake. RhodesMustfall was not about a statue; it was about reclamation and power and history. Similarly, the challenge today is not only about who should pay fees, but who should own the land. The discontent and anger about the ‘pay-to-play’ market system that we have – where only those who can pay for quality get it – is as much about private hospitals and Model-C schools as it is about universities. The true contested space at our universities at the moment is really about the principles that currently order our society and reimagining different ones.

Fighting for a different future

There are students in South Africa today who look at our country and refuse to accept that the way we are currently doing things is the only way they can be done. How is it that in a country with considerable wealth and resources that we still have 10 million people living on less than R10 a day? Whenever I land at Cape Town International Airport and get an aerial view of Khayelitsha, I think to myself “How the heck can we, as a country, not find a dignified solution to housing for the poor?” In Cape Town we have 400,000 people living in shacks a mere 40-minute drive from the house that sold for R290-million in Bantry Bay. We have decadent opulence living next to extreme poverty. It’s not right.

And so we come back to the contested space at universities where people have different ideas about how we get from where we are to a better future. Students associated with Black-First-Land-First argue for land expropriation without compensation. The Nobel Laureate Thomas Piketty motivates for much steeper wealth and inheritance taxes to level the playing field. The Wits SRC has proposed a once-off ‘apartheid windfall’ tax on “companies that benefited unfairly by abusing state resources” under apartheid.

But since the current discussions at universities are still centred on fees and access to university, let’s start there and think about what 2017 might hold for universities, and put some numbers on the table. Personally I think we will actually find a sustainable solution to student financing at universities, possibly even in 2017. Sizwe Nxasana – the head of the Presidential Task Team – has developed a highly sophisticated and workable model of student funding called the Ikusasa Student Financial Aid Programme (ISFAP) that is being trialled at seven universities this year, focussing on students studying medicine, engineering and accounting. This is essentially a public-private partnership which aims to “significantly increase the funding and resources which are made available to support students from working class families to graduate and find employment by leveraging private sector funding.” One can think of it as a three-tier model with the poorest students being fully funded with grants and the missing-middle with a combination of grants and income-contingent loans (to be repaid only if the recipient does graduate and earns above a certain amount). Then finally, those at the top that can pay fees do pay fees. While it isn’t free education for everyone – and the vanguard may therefore not accept it – if implemented properly it has a good shot at ensuring that no student is excluded from university on financial grounds. That would be a significant achievement.

Thankfully, many in the sector are now realising that needs-blind allocations to higher education – where all students are equally subsidised – are socially regressive and anti-poor. This is largely because the children of the wealthy attend fee-charging schools that give them a much better shot at qualifying for university than the children of the poor. We know that less than 1 in 10 children from the poorest 70% of households qualify to go to university compared to 1 in 2 or 3 children (40%) among the wealthiest 10% of households. And because of this, if one allocated an additional R10bn to higher-education in a blanket fashion, then about R6,8bn (68%) will end up benefitting the wealthiest 20% of South African households because it is their children who are disproportionately at university (according to two fiscal incidence studies). A recent study showed that 60% of students that qualified for university came from the 30% of high schools that charged fees. What is the point of raising revenue by additional taxes on the richest 20% only to give two thirds of that money straight back to them in the form of indirect subsidies to their children?

So if we agree that the rich should not be subsidised (usually defined as those in households with annual income of more than R600,000), how many students would need funding? Professor Servaas van der Berg’s analysis of household surveys has shown that about 60% of the current university-going population would be eligible for funding. (This assumes that income is under-captured in surveys by about 30% . Importantly, this would cover 73% of Black African university students and 30% of White university students.

While ending financial exclusion at university won’t solve the thornier issues in South Africa – about land, inequality, restitution, primary education, unemployment – it would serve as a powerful and invigorating example that things really can be different to what they are now. It would be poetic if the start of a successful campaign for a different South Africa could trace its origins to the toppling of a statue of Cecil John Rhodes.

Dr Nic Spaull is an education researcher at the Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP) group at Stellenbosch University. He is on Twitter @NicSpaull

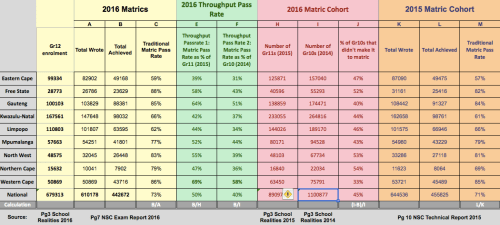

Every year there is a big song and dance about the matric exams and if the pass rate went up or down, which province came out on top etc. etc. Thankfully some organisations like Equal Education are directing our attention to where the root issue is: the weak foundations students get in primary schooling. There is ample evidence of this in maths and reading as the foundational bell-weather subjects that pretty much everything else is built on.

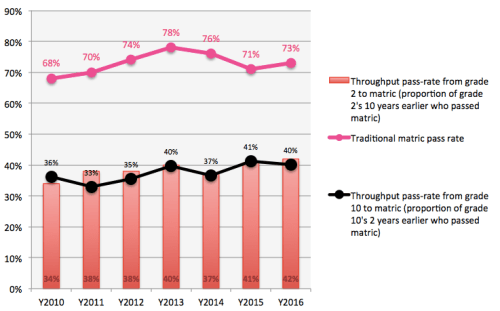

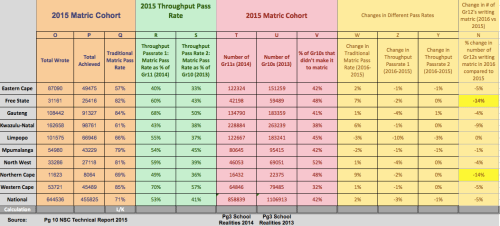

Throughput pass rates

As I’ve mentioned before we need to move beyond our myopic obsession with the matric pass rate and start seeing the results in light of other statistics, notably the throughput pass rate. Rather than calculating the number of students passing matric divided by the number of students writing matric (the traditional matric pass rate) we should also be calculating the number of students who pass matric relative to the number of students in grade 10 two years earlier and those in grade 2 ten years earlier (throughput pass rates). This gives us an idea of how many kids are dropping out along the way and if this is increasing or decreasing over time. (Note that this is also affected by the changing number of students repeating Grade 10. Because we don’t know the number of non-repeating students we have to use the total number of students enrolled in Grade 10).

From the above graph and table we can see the following:

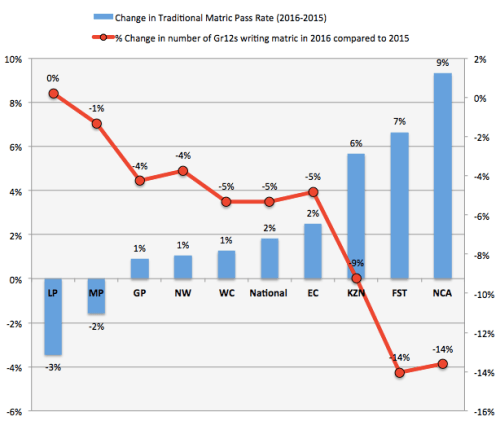

Standardisation and grade inflation

Secondly there is the issue of standardisation and adjustment. The quality-assurance body Umalusi is tasked with standardising the matric results so that no one year is disadvantaged relative to another. If the exams are more difficult/easy then Umalusi is allowed to adjust the marks upwards/downwards (by a maximum of 10 percentage points). As I discussed last year the presence of an extra 120,000 matrics in 2015 made the process of standardisation much more complicated than it had been in the past. We know these are weaker students and thus would have dragged down average performance, yet the decline in average performance in 2015 was attributed to more difficult papers.

“Was the test really so much more difficult than previous years? (This is the only reason why one is allowed to adjust the marks at all.) Why did the internal and external moderators not pick up the huge increase in difficulty? Is it not more plausible that the massive drop in pre-adjusted performance was actually due to the additional 112,000 weaker pupils who would have otherwise dropped out? If so, Umalusi shouldn’t have adjusted. (from here)”

In my view the standardisation of raw marks should be done without progressed learners included and then applied to progressed learners after the fact. You cannot compare the 2015 and 2016 cohorts (and to some extent the 2014 cohort) with earlier cohorts because they did not have progressed learners. I think this remains an open question and I am quite anxious about the very large adjustments that Umalusi is making, assuming that the tests are getting much more difficult when the most plausible explanation is the inclusion of many more weaker students that typically would have dropped out in the past. (In 2015 the number of students passing maths literacy increased from 38% to 71% and there were similarly large adjustments in 2016). If I am right about this, and there is essentially a lot of grade-inflation going on, then we are likely to see universities increasing their NSC points entrance criteria and – something which we have already seen over the last 6 years – the use of other criteria like the National Benchmarking Tests.

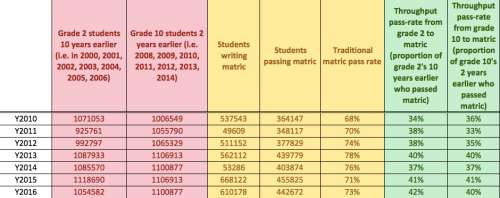

Provincial performance and sample selection

Every year the media likes to highlight which province has done the best in the matric exams. The competition is usually between our two wealthiest provinces (surprise surprise!), which are Gauteng and the Western Cape. In 2016 the Free State had the highest matric pass rate of 88% and so MEC’s and bureaucrats were all commending the Free State for their achievement. But if we dig a little deeper there are a few thorny questions here…

In 2011 Nick Taylor argued that changes in the matric pass rate can be driven by many things, including the difficulty of the exams, subject combinations and the number of students that actually make it to matric. This later point is the one I want to highlight here – the practice of not letting weaker students get to matric, sometimes referred to as gate-keeping or — and I hate this term — ‘culling’).

When I heard that the Free State and the Northern Cape had increased their matric pass rates significantly (7 and 9 percentage points respectively), my first question was “But did they hold back more students than last year?” So let’s see what the numbers say. Does there seem to be a relationship between the number of Grade 12s writing matric between 2015 and 2016 and a change in the pass rate over the two years? Let’s see…

So, the three provinces with the largest increases in their matric pass rate also had the biggest declines in the percentage of students writing matric. That’s pretty strange. So if we do a similar analysis to the throughput pass rate above but at a provincial level what do we see? The Free State is no longer first but 4th of the provinces with the Western Cape and Gauteng at the top. And the Northern Cape and KZN are now only marginally better than Limpopo – the second worst performing province.

There may well be a legitimate explanation for this but our first port of call when seeing a big change like this is a change in the underlying sample. Before we start asking what interventions the Free State implemented we should be asking if the ‘increase’ is legitimate. At least at face value there seems to be a lot more sample selection in the provinces with the highest increases in matric pass rates. And judging from the Grade 10 (2014) and Grade 11 (2015) cohorts it doesn’t look like there was a population decline in these provinces.

So to sum up the above I’d say the following:

So now, I need to get back to Foundation Phase reading research 🙂

The excel file with the above tables/graphs/figures is here in case anyone wants to do their own calculations/graphs.

Posted in Education, Matric, Uncategorized

(The article below first appeared in the Sunday Times on the 16th of October 2016)

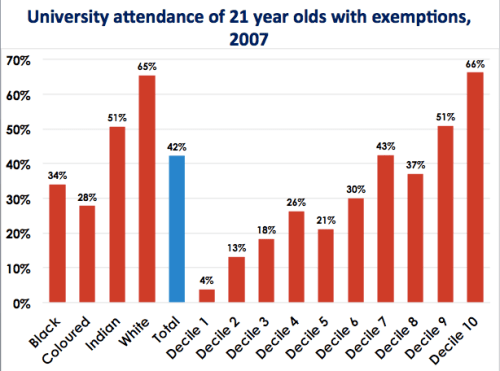

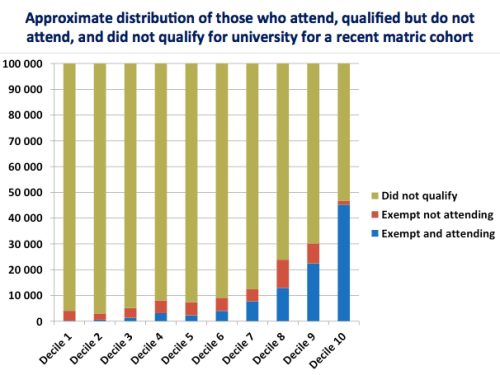

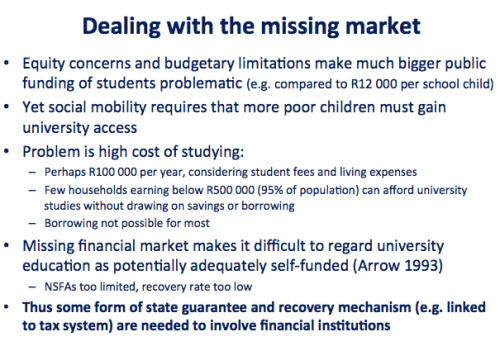

Across the country student protests have shut down universities with demands for “free higher education for all” prompting a Fees Commission and more recently a Presidential Task Team of Ministers to help solve the crisis. At the root of the issue is the righteous indignation about the fact that academically deserving students are excluded from university (either initially or subsequently) because they cannot pay their fees or living expenses. After overcoming countless barriers to simply get to university, these resilient students are then excluded simply because they are poor. This is unacceptable. I whole-heartedly agree with the underlying principle that no student should be excluded from university on financial grounds, which is unfortunately the status quo. Note that this is not the same as saying I think we should have “free higher education for all.” I think that subsidizing the richest 10% of South African households is unconscionable and unjustifiable, and “free education for everyone” is exactly that: a subsidy for the rich. Let me explain why.

Firstly we have to ask who makes it to university? A recent study published last month by my colleagues Dr Hendrik van Broekhuizen and Professor Servaas van der Berg shows that of 100 children that started school, only 14 will qualify for university, 12 will actually enrol and only 6 will get some kind of undergraduate qualification within 6 years. So when we speak about university we are really speaking about the 12% of students that actually make it to university. And who are the students that qualify? In a recent matric cohort, about 60% of those that qualified came from the wealthiest 30% of high schools (quintile 4 and 5), most of which charged fees. And who attends fee-charging schools? Largely those wealthier students whose parents can afford the fees. We can also look at this by race; about half (47%) of white matriculants go to university compared to less than a fifth of Black (17%) and Coloured (20%) matriculants.

This explains why blanket fee-free education is considered to be highly regressive or anti-poor. In contrast to a free-for-the-poor system which is pro-poor. The fact that the children from the wealthiest households are many times more likely to get in to university means that they would benefit disproportionately from a blanket fee-free system. It should thus come as no surprise that the World Bank (2014) and Van der Berg (2016) both estimate that as much as half (48%) of the university funding in South Africa accrues to the richest 10% of households. And two thirds (68%) accrues to the wealthiest 20% of households. As Van der Berg notes, this constitutes an “extreme bias towards spending on the rich if all students are equally subsidised.”

What is the point of raising revenue by additional taxes on the richest 20% only to give two thirds of that money straight back to them in the form of indirect subsidies to their children? No, instead we should use all the revenue raised from the additional taxes – however much that might be – to properly fund the poorest 80% of students who manage to qualify against all odds and who really need the funding.

The next question then becomes what the best modality is for ensuring that no student is excluded from university on financial grounds. While ideologically students may be demanding ‘free-education for all’, the existing economic environment of depressed economic growth and fiscal consolidation means that it is not easy to find an additional R60bn of recurrent expenditure. It is not a cop-out when Treasury says that it cannot simply ‘find’ an additional R60bn every year. To put this in perspective, the entire government budget of the Western Cape is R55bn. Health, housing, education, everything. We also need to grapple with the issue that additional money allocated to higher education is likely to crowd out other budget items like the progressive realisation of other constitutional imperatives such as universal health care (National Health Insurance) or universal housing.

Personally I am in favour of raising taxes (the skills tax and the capital gains tax) to fund poor and working class students who are currently financially excluded from university. Yet we need to go further than that to cover the “missing middle.” I think that a hybrid system of grants, subsidized loans and fees would lead to the largest reduction in financial exclusion, irrespective of how much is raised. The poorest students would receive ‘free’ education in the form of adequate grants that cover both fees and living expenses. The missing middle would qualify for government backed loans whose repayment was contingent on graduating and earning above a certain threshold (income-contingent loans), and the wealthy would pay fees, as they are currently doing. Those students who get government-backed loans would carry little financial risk, receive subsidized interest rates and capped loan repayments that would only revert in the event that they earn above a certain threshold. The leveraging effect of using the existing financial markets and banks means that, for example, R15bn of additional revenue could stand surety for loans of up to R60bn. So while it might only be possible to raise an additional R15bn – through a 1% rise in the Skills Levy for example -, one could ensure that no students are excluded on financial grounds. This is not politically sexy or glamorous, and doesn’t have a catchy hashtag (yet) but it does grapple with the budgetary realities we face as a country.

It is not at all clear to me why the different student movements are insisting on free education for everyone (including the rich) in spite of all the evidence that this would be fiscally irresponsible and socially regressive. Subsidizing the rich wastes precious tax income that could otherwise have supported more poor and working class students. Furthermore, if we can shift the conversation from an ideological (but unworkable) “Free Education For All” to a pragmatic “Funding For All” we will be taking a big step in the right direction.

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, Uncategorized

I have been meaning to blog about some new research on access to higher education that was published earlier this week: “Higher Education Access and Outcomes for the 2008 Matric Cohort” (Van Broekhuizen, Van der Berg & Hofmeyr, 2016). I will only highlight some of the key points from the 122-page Working Paper which is really worth reading in its entirety. Essentially the researchers used the matric data from 2008 and followed these students (using their ID numbers) into the higher education system using data from the Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS). Perhaps the most striking feature is that of the 100 students that started school, only 12 ever access university (9 immediately after matric and 3 later), 6 get some kind of qualification within 6 years and only 4 get a degree within 6 years.

Secondly, that matrics that attend quintile 5 schools (almost all of which charge fees) are four times as likely to access university than those from the poorest 60% of schools (quintiles 1-3), all of which are no-fee schools. However, it’s encouraging to note that of those quintile 1-3 student that do qualify with a bachelor’s pass, more than 63-68% do actually access university, compared to 70% among quintile 5 students.

Much of the paper points to that fact that unequal access to university is rooted in a highly unequal schooling system where access to high-quality schooling largely depends on a family’s ability to pay school fees. If one looks at the cumulative matric average achievement by race one still finds enormous differentials. While 60% of White matric students achieved 60% or more in matric, only 5% of Black African matrics score at or above 60%. And this is only among the students that actually made it to matric which is only slightly more than half the cohort (see this paper).

The last piece of their research that I want to highlight is that the student intake at different universities is vastly different. If one looks at the matric marks of the typical student entering UCT, Stellenbosch, UP or Wits one can see below that they scored 70% or above on average. This is in stark contrast to those students entering TUT, Fort Hare, Uni-Zulu, Walter Sisulu, UWC etc., all of whom have incoming students whose average matric mark is less than 60%. At the Central University of Technology (CUT, in Free State) the average entrant scored 50% in matric.

At the beginning of last year Professor Servaas van der Berg gave a Brown-Bag Lunch Seminar at Stellenbosch University on “The Distributional Implications of Student Fees.” I include some notable excerpts and graphs below:

“Education has a number of properties which make the analysis of the demand for it both interesting and complex. … (Education is) …a consumption good and a capital good, i.e., although much of the expenditure is justified in terms of the effects on the individual’s income in the future, many of the activities of educational institutions are primarily justifiable in terms of their immediate consumption benefits. Moreover, education affects individuals’ future incomes.” – (Stiglitz 1974: 349)

Perhaps most striking are Van der Berg’s estimates of who actually makes it to university and where they come from in the income distribution. According to these estimates, there are more students attending university from the richest 10% of the income distribution (Decile 10) than from the poorest 80% of the income distribution (Deciles 1-8 combined).

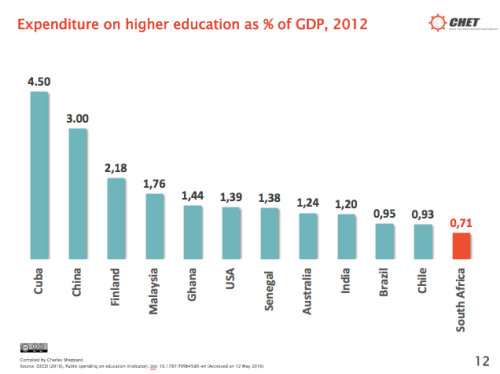

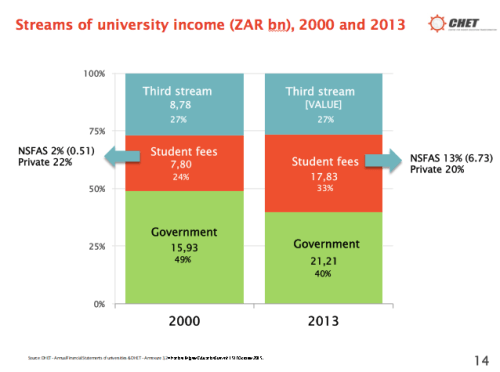

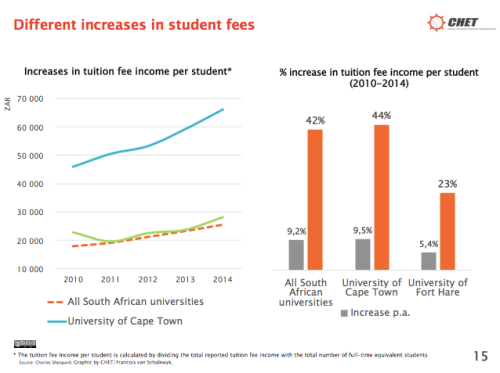

Last month Nico Cloete (from CHET) gave a lecture at SALDRU (UCT) titled: “University Fees in SA: A Story from Evidence.” I include some relevant slides from his presentation:

Anyone who wants to contribute to the debate about university fees needs to grapple with the realities presented by these three papers/presentations. At the end of the day we need to be able to answer the question of where the money will come from. A Graduate tax? Debt? The Education or Health budgets?

The most reasonable (and probably workable) solution that I have heard is that proposed by Prof Van der Berg who suggests that we should use the existing financial services infrastructure (banks) who could provide government-backed grant-loans (my terminology not SVDB’s) to students that qualify for university. It would be a grant that converts into a loan if a student successfully completes their degree and starts earning a decent income. It would still require a huge amount of government finance to provide the surety to banks for students who come from households that earn less than R500,000 (or some threshold). But, unlike with totally ‘free’ education, the students that do successfully complete their degrees would ‘pay-it-forward’ and contribute to the fund used to finance future students.

Also, as a side-issue, the Fees Commission needs to get a fast-tracked timetable and told to release at least a preliminary report and recommendations before the end of the year. We cannot wait until June next year. The political hot-potato would have been passed along one too many times from VCs to DHET to Treasury and eventually it will just explode. A stitch in time saves nine.

(If you have any additional research suggestions please send me an email and I’ll include them in this post)

Additional inputs from readers:

“Between the Devil and Deep Blue Sea? The Financing of Higher Education” 3×3 article by Philippe Burger – Sept 2016 (Thanks Marisa!).

Abstract: “Higher-than-inflation increases in student fees since 2009 often are blamed on declining government subsidies to universities. This is not entirely correct, if one considers real per-student subsidies. Fee increases resulted mainly from cost pressures faced by universities due to growing student numbers and a weakening rand. These pressures will not disappear. Eliminating government wastage is not a durable solution and difficult choices cannot be avoided. So, who should pay for increasing costs, students or government – or which combination of these?”

“Kagisano Number 10 – Student Funding” – CHE (April 2016)

Description: The tenth issue of the CHE’s journal, Kagisano, brings together a number of papers that were presented at a CHE colloquium on student funding that was held in December 2013. The colloquium took as its point of departure the Funding chapter of South African Higher Education Reviewed, and the various papers, presented by experts who responded to a call for papers, all address in different ways the student funding crisis that reached a head with the #feesmustfall campaign in late 2015, and that continues to underlie student unrest in higher education. Different ideas on how to restructure student funding are presented, and the solutions range from the philosophical to the practical. This issue aims to contribute to the ongoing conversations, negotiations and policy-making aimed at ameliorating the intractable challenge of how to fund increasing access to higher education while ensuring that students receive a quality higher education experience.

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

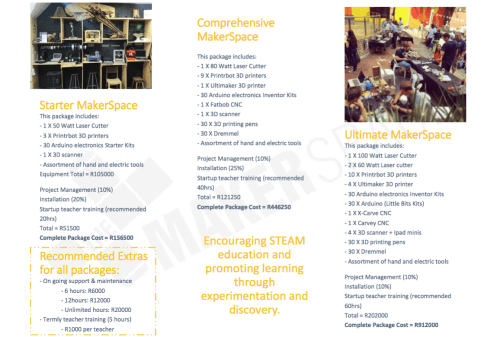

If you’re interested in 21st Century Skills (like Creativity, Collaboration, Critical Thinking, Communication), you should be looking into MakerSpace which now has a branch in Durban 🙂 The aim is a kind of ‘make it yourself’ drive, and helps by providing the skills, tools and training to do it. For education this might be about 3D-printing, or how to use and program an Arduino, or Robot Making (see pamphlet below). This reminded me of Stanford’s FabLearn Labs which works on a similar logic (the photo above is of a FabLearn Lab). If your school can afford these types of courses I would strongly recommend moving in this direction…

You can find out more here – http://themakerspace.co.za/

Posted in 21st Century Skills, Education, Uncategorized

I have now moved to Paris to work at the OECD for my TJA Fellowship on PISA data in developing countries. This is essentially an extension of my work on SACMEQ/PASEC and DHS, trying to combine surveys of achievement and attainment to get a composite measure of education system performance. While I’m away I won’t be commenting as regularly on SA education issues as I usually do. And I will probably shift my focus to other developing countries which is the topic of my research at the OECD. I have already found a number of fascinating things about some PISA countries which I don’t think are widely known or fully appprecaited. There is more than enough included in my previous blog post (11 policy briefs, two synthesis reports and a 200+-page special issue of the SAJCE), not to mention the Volmink Report, for the media and policy-makers to focus on for the next 2 years, let alone 3 months. Keeping up with the nitty-gritty doesn’t make much sense when the underlying issues are not being addressed or taken seriously.

To be honest I’m quite glad to be taking a break from South African education and working on PISA and learning about PISA-for-Development. Clear outcomes, a competent team, and political will. That’ll be nice 🙂

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

For the last two years we at RESEP have been working on two major education projects: The “Binding Constraints” project (Presidency/EU) and the “Getting Reading Right” project (Zenex Foundation). We launched the two reports on Tuesday last week (my presentation is here). Included below are the two project synthesis reports, a detailed outline on a prospective course (which needs a funder) on “Teaching Reading (& Writing) in the Foundation Phase” and 11 policy briefs. I’ve also included the “Roadmap for Reading” which provides a detailed outline of the practical steps that the Minister of Education could take if she wanted to prioritise reading in the Foundation Phase.

All of the above are also available on the RESEP website here. The 2015 special issue of the South African Journal of Childhood Education (SAJCE) where most of the research was published is available here (ungated) for those who would like to read the full journal articles.

The presentations from the event are available here:

(I would especially encourage everyone to read through Servaas’ and Gabi’s presentations, they were exceptional!)

There is obviously a lot to be said about these two projects, some of the new research points to very tangible, actionable steps to improve the education system, decrease inequality in outcomes and arguably create a fairer and more efficient education system. Yet it is not at all clear that any of these suggestions will be followed. It was unfortunate that neither the Director General nor the Minister were able to make the report launch. I am aware that both have very busy schedules and that a lot has been happening in education in the last few months. I hope that Servaas will have an opportunity to present this research to them in the coming months. I have also been underwhelmed by the online coverage of the research.

I deliberately do not want to write about the research now since I am currently a little jaded and frustrated about the education research, funding and policy space (perhaps you can tell!). When there are clear, unambiguous and actionable steps that could be taken to improve the education system and they are not taken, this is frustrating. When funders choose to channel millions (billions?) of rands in fruitless directions toward unevaluated projects, it is frustrating. When clear priorities and needs are ignored by national government and local funders (like developing a high-quality course to teach foundation phase teachers to teach reading!), it is frustrating. And perhaps most frustrating of all is the large number of people in provincial and national government that are unable to do the jobs that they have been appointed to do. While there are a number of dedicated and competent public servants and politicians in education, the way that our system is set up means that they have to rely on people who cannot do what they are being asked to do. Those people need to be trained quickly or performance-managed out of the system. That will take courage, strategic leadership and a clear understanding that the status quo is preventing poor children from quality education. Indeed “Weak institutional functionality” or “Insufficient State Capacity” was one of our four binding constraints. Go figure.

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

This was first published in the Mail & Guardian on the 13th of May 2016. The PDF of the article is also available as text below:

Black graduates have doubled in last 10 years – Dr Nic Spaull

As someone who has written quite extensively about the failings of our education system, I was unusually surprised by the quotes emerging in the media coverage of a recent Stats SA report and even more so by the Statistician General Pali Lehohla’s comments last week. Following publication of the report, titled “The Social Profile of Youth”, the Business Day was quick to inform us that apparently black youth were “less educated now than 20 years ago.” The Daily Maverick ran a similar headline: “Stats SA claims black youth are less skilled than their parents”, with equally alarmist coverage in Times Live, ENCA, SABC etc. Unfortunately StatsSA did not denounce the media’s claims. The story seems to have grown legs, with former president Thabo Mbeki calling it a “national emergency” and the Shadow Minister of Basic Education speaking of “the collapse of education in poor communities.”

Of course none of this is true. As we shall see, Black youth have higher levels of educational attainment today than at any other point in South Africa’s history. There are more Black matrics, more black high level passes in mathematics and science, and many more Black university graduates. (Note that this is both as a proportion of the Black population and in absolute terms). In this article I will focus on black university graduates since everyone agrees that there have been large increases in black youth passing matric and achieving bachelor’s passes.

If we cut to the chase the confusion all centres on one strange graph (Figure 4.2) appearing on page 64 of the 2015 Stats SA report “Census 2011: A profile of education enrolment, attainment and progression in South Africa” and the misinterpretation of what that graph apparently shows. That graph shows that the proportion of black and coloured youth that graduate with a bachelor’s degree “after completing matric” has been declining for 20 years, while for whites and Indians it has been increasing. This is very strange and does not seem to agree with other, perhaps more reliable data sources. Unlike when trying to measure things like the unemployment rate or wages (where you have to turn to household survey data or the Census), when counting the number of university degrees awarded it’s a little easier. We can look at surveys, but we can also just look at the Higher Education Management Information System (Hemis) the record-keeping system stating who has been granted what degree and when. All degrees that are granted must be recorded on this database. So what does Hemis tell us about the number of black youth actually getting degrees over the last 20 years?

Fortuitously, this exact question was addressed in a Stellenbosch Economic Working Paper (08/16) published last week by my colleague Dr Hendrik van Broekhuizen. In that paper he shows that “while the number of White graduates produced annually has increased only moderately from about 27 500 to just over 35 000 in the past 25 years, the number of Black graduates produced has increased more than 16-fold from about 3 400 in 1986 to more than 63 000 in 2012.” For this article I was particularly interested in degrees rather than diplomas or certificates) and he kindly provided the figures for degrees only by race (see figure below). The changes have been equally dramatic. Between 1994 and 2014 the number of black graduates with degrees being produced each year has more than quadrupled, from about 11,339 (in 1994) to 20,513 (in 2004) to 48,686 graduates (in 2014). Even if one only focuses on the recent period between 2004 and 2014 Black graduates increased by about 137% (compared to 9% for whites), while the black population grew by about 16% over the same period.

This might lead us to yet another famous South African myth; that graduate unemployment is high (it isn’t) or increasing (it’s not). Again, rigorous research by Dr Van Broekhuizen and Professor Servaas van der Berg convincingly debunks this hoax. They conclude their research report as follows: “The frequently reported ‘crisis in graduate unemployment’ in South Africa is a fallacy based on questionable research. Not only is graduate unemployment low at less than 6%, but it also compares well with rates in developed countries. The large expansion of black graduate numbers has not significantly exacerbated unemployment amongst graduates….Black graduates are, however, still more likely to be unemployed than white graduates.” (Note: in 2015 black graduate unemployment was about 9% compared to 3% for whites.) [Their extended article is here]

Another colleague of mine, Dr Stephen Taylor in his response to the Statistician General (Business Day, 29 April) has shown why Stats SA’s Figure 4.2 is so misleading (essentially the increase in black matrics was larger than the increase in black graduates, but both increased substantially). Unfortunately the SG has simply lashed out at Dr Taylor referring to his critique as “technically incomprehensible and policy irrelevant” (Business Day, 5 May). To avoid a similar riposte let me be clear: Black graduates have more than doubled in the last ten years. The black population hasn’t. Therefore, black youth are more likely to get degrees than 10 years ago. I think this is both technically comprehensible and policy relevant.

The argument that “black youth are regressing educationally” feeds a dangerous narrative that is not supported by any education data in South Africa. Not improving fast enough, yes. Regressing, no. Black youth have higher educational attainment now than at any point in South Africa’s history. This does not change my firmly held view that our education system is in crisis and that we need meaningful reform, that goes without saying. The egregious levels of educational inequality between working class and middle-class families, and between whites and blacks should cause alarm. And yes, our youth unemployment problem is monumental and unsustainable; there is widespread and legitimate research to show that. But spreading fallacious rumours and causing doubt where there is none, helps no one. Together with a number of colleagues and officials I would ask the Statistician General to please clarify his comments on black graduates and set the record straight.

//

Dr Nic Spaull is a Research Fellow at the University of Johannesburg, the University of Stellenbosch and the OECD.

Workings for graphs (thanks Hendrik van Broekhuizen!)

| Year | Black | Coloured | Asian | White |

| Y1986 | 2957 | 1131 | 1532 | 17601 |

| Y1987 | 3153 | 1280 | 1692 | 19064 |

| Y1988 | 3546 | 1349 | 1771 | 20494 |

| Y1989 | 4043 | 1760 | 1930 | 21613 |

| Y1990 | 4862 | 1958 | 1975 | 22747 |

| Y1991 | 7115 | 2230 | 2170 | 23800 |

| Y1992 | 8130 | 2270 | 2363 | 24901 |

| Y1993 | 8661 | 2392 | 2621 | 24571 |

| Y1994 | 11339 | 2127 | 3023 | 25538 |

| Y1995 | 13123 | 1833 | 2506 | 16885 |

| Y1996 | 15781 | 1785 | 2479 | 16363 |

| Y1997 | 17367 | 1869 | 2713 | 16385 |

| Y1998 | 17181 | 1949 | 2796 | 15650 |

| Y1999 | 19093 | 1785 | 2175 | 15410 |

| Y2000 | 20379 | 1909 | 3193 | 15896 |

| Y2001 | 17017 | 1913 | 3430 | 16017 |

| Y2002 | 16222 | 2075 | 3712 | 17094 |

| Y2003 | 17234 | 2322 | 3776 | 17948 |

| Y2004 | 20513 | 2640 | 4307 | 18757 |

| Y2005 | 21052 | 2916 | 4505 | 19860 |

| Y2006 | 22508 | 3097 | 4805 | 20732 |

| Y2007 | 23356 | 3480 | 4840 | 20522 |

| Y2008 | 25373 | 3677 | 4984 | 20482 |

| Y2009 | 27869 | 3866 | 4774 | 20555 |

| Y2010 | 31453 | 4366 | 4690 | 20456 |

| Y2011 | 34209 | 4456 | 5109 | 20248 |

| Y2012 | 40001 | 4778 | 5089 | 20303 |

| Y2013 | 45948 | 5291 | 5748 | 21548 |

| Y2014 | 48686 | 5622 | 5529 | 20510 |

*These include the following: General Academic Bachelor’s Degree; Professional First Bachelor’s Degree; Baccalaureus Technologiae Degree; Professional First Bachelor’s Degree; First National Diploma (3 years); First National Diploma (4 years)

| Figures refer to the number of HE awards and will thus be at least as large as the number of graduates produced in each year. Includes only undergraduate degrees. (Thus excludes all UG diplomas, and certificates |

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, Uncategorized

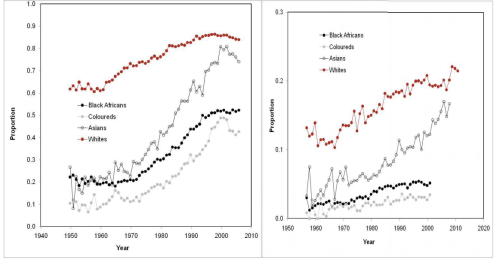

Figure 1: Proportions of the population achieving secondary education (left) and a bachelors degree (right). (Source: Stats SA (2015): CENSUS 2011: A profile of education enrolment, attainment and progression in South Africa, page 41.)

On the 18th of April the Business Day published a piece titled, “Black youth less educated now than 20 years ago.” This statement is simply wrong and unsupported by any data set. Yet the story is now gaining momentum and has been published by other news outlets, such as the Daily Maverick, reporting that “Stats SA claims black youth are less skilled than their parents.”

The article asserts that “black and coloured youths have regressed in their educational achievements” and that the proportion of black and coloured youth that complete a university degree as a share of the population has decreased. This is factually incorrect.

The article references a recent Stats SA report on the status of the youth as well as comments by the Statistician General, Pali Lohohla, as the basis for these assertions.

But in fact, the Stats SA published reports (as with all other analysis I have seen or done) indicate that the proportions of black and coloured youths who attain grade 9, grade 12, and a university degree, have all increased consistently in recent decades and are still increasing. It is thus not clear where this misconception arose.

I suspect the mistake may have arisen through a misunderstanding of a statistic which has been presented by the Statistician General recently and which appears in Stats SA’s report on educational enrolment, attainment and progression (December 2015). The statistic shows that the proportion of black and coloured youths who achieve a bachelors degree “after completing grade 12” has been declining over the last 20 to 30 years.

It needs to be understood that this statistic is the proportion of matriculants who go on to attain a degree. In other words, the denominator in this calculation is matriculants as opposed to the entire black and coloured population.

The improvement in matric attainment among black and coloured youth has been larger than the improvement in degree attainment among black and coloured youth, but – and this is the important part – there have been big improvements in both. The fact that the increase in degree completion has been slower than the increase in matric completion is not at all an indication that youth are worse off now than 20 years ago.

So the ‘bad’ news is that degree completion, although it has increased, has not kept pace with the fast increase in the attainment of matric amongst black and coloured youths. But this certainly does not mean that educational outcomes are worse than 20 years ago.

So what do the numbers actually say? The Stats SA report issued in December shows that the proportion of black people completing matric has been consistently increasing from about 20% to about 50% over the last 50 years. That report also indicates that the proportion of black people completing a degree has increased from about 2% to about 4% over the same period.

Whether you read official Stats SA reports or do your own calculations on the various Stats SA datasets – I have analysed Census data from 1996, 2001 and 2011 as well as General Household Survey data from 2002 to 2014 – it is clear that both matric attainment and degree attainment has been increasing amongst the black and coloured population.

It is also useful to consider the Department of Basic Education’s matric statistics from recent years. In 1990, there were 191 000 matric passes. By 2015 this number had more than doubled to 465 863. This increase has been driven mainly by growing numbers of black youth passing – and this growth has easily outstripped population growth, which has been about 1% a year. Even since 2008, the number of black matric passes has increased from about 250 000 to over 350 000. And the number of black people achieving a bachelors pass in matric has increased from about 60 000 to about 120 000 since 2008.

I am by no means suggesting that everything is fine in our education system. Despite the progress, there are still too many youths who do not get to grade 12, the main reason being that educational foundations laid in earlier grades have been inadequate. And completion rates at our higher education institutions should worry us. But there have been improvements in both of these areas relative to 20 years ago.

Although improved access at lower levels of education (primary and secondary school completion) has been faster than access at higher levels, paradoxically the solutions must focus on the early grades if sustainable progress is to be made.

The most alarming education statistics to me are the low proportions of children achieving basic literacy and numeracy in the early grades. International assessments of education quality point to serious deficiencies in this area, even compared to some other countries in the region. If children are not learning to read in the early grades, they will not be able to make it to higher education.

But even in the area of learning quality, the evidence points to improvement. The Trends in International Mathematics and Science study (TIMSS) showed substantial improvements in mathematics and science achievement at the grade 9 level between 2002 and 2011. However, this improvement is off a very low base.

Educational outcomes in South Africa remain far too low, especially amongst youths from poor communities. But claims that education was better under apartheid or that outcomes have deteriorated over the last 20 years are alarmist and have no basis in reality.

—

Dr Stephen Taylor is a researcher in the South African Department of Basic Education. His work includes impact evaluation of education interventions, measuring educational performance and equity in educational outcomes. In 2010 he completed a PhD in economics at the University of Stellenbosch, analysing educational outcomes of poor South African children.

(This article first appeared in the Business Day on Friday the 29th of April 2016)

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, Uncategorized

Whenever I travel overseas I am asked the question “What is the biggest problem in South Africa?” And I typically respond, “The biggest problem or the biggest solvable problem?” In the 2000’s the biggest problem was HIV/AIDS. After hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths – the equivalent of a small genocide – the government ceded to the courts and offered life-saving ARVs to those infected with HIV and saved their lives. HIV was, and is, a solvable problem. Unfortunately the three biggest problems in South Africa today – too few jobs, too little growth, and too much inequality – are not easily solvable. And because we don’t exactly know how to ‘create’ jobs or growth, we don’t really know how to decease inequality much further.

Of course everyone has theories about how we can increase jobs, but the evidence is pretty thin. Depending on your political fancy and chosen economic guru there are various concoctions ranging from youth wage subsidies, eliminating red-tape, decreasing taxes, increasing taxes, digging holes, filling holes…you get the picture. Ask the top labour-economists in the country how to create jobs and you won’t get a straight answer (This is partly a provocation to said labour economists to tell us if there is in fact any coalesced consensus). You won’t even get consensus on the next three steps towards finding the answer; which is, incidentally, not a uniquely South African problem. So what to do? I think the best response is to keep cracking away at the problem; experimenting, evaluating, moving forward. But in the mean time we should also be allocating time, energy and resources to solvable problems; those we haven’t currently cracked but have a pretty good idea of how to do so. Epidemic HIV; distribute free ARVs. Crippling poverty; introduce the child support grant. Widespread malnutrition; provide free school meals to most children. The government should be heavily praised for all of these important initiatives.

But the problem I want to focus on here is the fact that most kids do not learn to read in lower-primary school. South Africa is unique among upper middle-income countries in that less than half of its primary school children learn to read for meaning in any language in lower primary school.

Irrespective of how tenuous or strong you believe the relationship is between education and economic growth, teaching all children to read well is a unanimously agreed upon goal in the 21st century. It is necessary for dignified living in a modern world, it is necessary for non-menial jobs, it is necessary for a functioning democracy. It also usually helps with ignorance, bigotry and a lack of empathy. In a modern context illiteracy is a disease that is eradicable, unlike unemployment or inequality. Like polio, illiteracy practically does not exist in most wealthy or even middle-income countries (defined here as basic reading). Illiteracy rates among those who have completed grade 4 are in the low single digits in wealthy countries like England (5%), the United States (2%) and Finland (1%) and less than 50% in most middle income countries such as Colombia (28%), Indonesia (34%), and Iran (24%). It’s difficult to get directly comparable estimates for the whole country but the best estimate from the recent pre-Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) surveys is about 58%. That is to say 58% of Grade 4/5 students cannot read for meaning in any language. And why is Grade 4 a critical period? The South African curriculum (like most curricula) prescribes that in the first three years of schooling children must ‘learn to read’, then from grade 4 onwards they must ‘read to learn’. The fact that almost 60% cannot learn through reading means that these children cannot really engage with the curriculum beyond grade 4. It really isn’t much more complicated than that

Reading for meaning and pleasure is, in my view, both the foundation and the pinnacle of the academic project in primary school. Receiving, interpreting, understanding, remembering, analyzing, evaluating and creating information, symbols, art, knowledge and stories encompasses pretty much all of schooling. Yet most kids in South Africa never get a firm hold on this first rung of the academic ladder. They are perpetually stumbling forward into new grades even as they fall further and further behind the curriculum.

Based on my reading of the academic literature – which may differ from others – there are three main reasons why the majority of kids don’t learn to read in lower primary school.

For me the solution is simple: we need to address these three problems: (1) decide how to teach existing and prospective teachers how to teach reading (as is done all over the world in contexts as linguistically and socioeconomically complex as our own), (2) ensure that all primary schools have a bare minimum number of books and that these are managed effectively, (3) monitor how often teachers are actually teaching and introduce meaningful training first and real consequences second for those teachers who are currently not teaching.

We may not have consensus on how to create jobs or increase growth, but there is consensus on how to teach children to read: with knowledgable teachers who have books and provide their students with enough opportunity to learn. If you want to improve matric, you need to start with reading. It’s not rocket science.

*This article first appeared in The Star on Tuesday the 29th of March

**Image from here

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, reading, Uncategorized

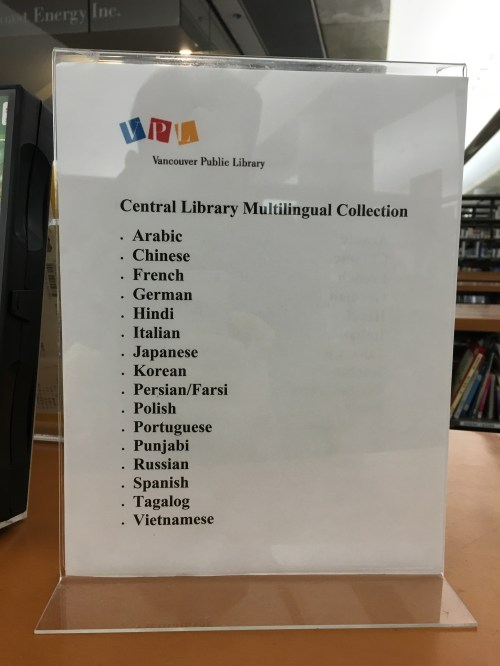

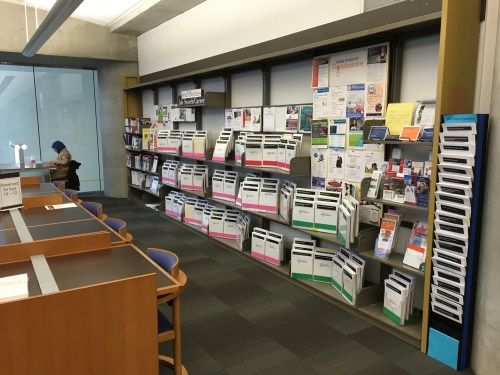

I recently had the privilege of visiting the incredible Vancouver Public Library for a few hours on Sunday morning and was totally blown away (thanks Kelsey for recommending it!). I was at the CIES education conference in town during the week and in hindsight I wish I had just spent it talking to the librarians instead, documenting what, how and why they do what they do. As it turns out, while I was wandering the floors of the library I was actually in the process of missing my flight home! In the end I had to book a series of one-way flights home which turned into a long (52-hours!) and expensive journey back to Cape Town. Nevertheless, I probably wouldn’t have had time to visit VPL had I not missed my flight. C’est la vie.

If I’m honest I found parts of my VPL experience a little emotionally overwhelming. I don’t think this was because of the library itself but rather because of the Canadian values and philosophy that it embodied. Walking around Vancouver and seeing various public announcements all in multiple languages was mirrored at VPL where half of an entire floor was dedicated to books published in other languages.

There were also some children’s books in other languages but not nearly as many (or as diverse) as in the adult books section.

The part that I found quite emotional was the “VPL Skilled Immigration Information Centre” which helps newly resident skilled immigrants find work. They have created 8-10 page booklets on each career with information on things like starting salaries, industry websites, and who the large employers are in that field. In the handbook on ECD practitioners there was even a section on “hidden jobs” and how to access these (jobs that aren’t advertised anywhere!).

Like many people I have been following the US presidential nominations and the contrast between the Canadian and American responses to the Syrian refugee crisis are just worlds apart. America has agreed to welcome 10,000 Syrian refugees while Canada is taking in 25,000 Syrian refugees (Note: American population: 319 million, Canadian population: 35 million). But for me it actually wasn’t about the numbers it was about the tone and the attitude towards refugees (and diversity in general). This was one of the posters in the library:

The day before I was taking the bus to the Capilano Suspension Bridge Park and saw a photo of a Syrian girl on the side of the bus with an explanation that the government of Canada would match dollar-for-dollar any donation Canadians made to charities supporting the Syrian refugees (Red Cross, UNICEF, Save the Children etc.), and that this was up to $100 million. Once at Capilano I was also encouraged by the way that the official guides spoke of the traditions and knowledge of the First Nations people. As we walked around the park the guides told us why the First Nation’s people named certain trees the way they did and about their cultural traditions and practices. At no point did I feel that they were being exoticised or belittled. Their insights and names were woven into the park’s signs and boards and included in the children’s treasure/science hunt maps.

Back to the library, this disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

disposition towards diversity was strongly emphasised. The library not only has an Author-in-Residence, but also an Aboriginal-Storyteller-in-Residence aiming to foreground and highlight the oral tradition of the aboriginal people.

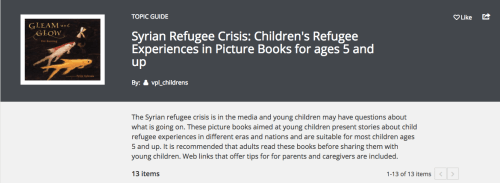

Throughout the library there were references to Syria and the refugee crisis with materials, both for Canadians and Syrians. In the children’s section there was even a list of picture books about refugees from other countries to help children understand what was going on.

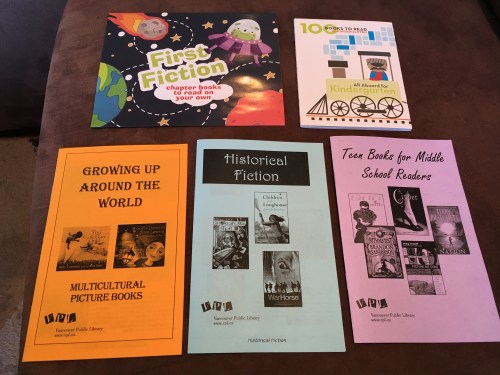

I was so impressed by the work that the children’s librarians had done. There were curated reading lists for different age groups and different topics with brief explanations of each book next to a picture of the front page. The front covers of each booklet are included below:

Forging the path of what a library looks like in the 21st century

Another thing I was struck by was how modern and professional everything looked. Apart from things like couches, computers, wifi and art, I got the distinct sense that the library was trying to claim for itself a space in the digital age. At the VPL Inspiration Lab there were multiple recording rooms with specialist microphones and video-cameras, green-screens, conversion devices (digitising VHS, for example). And all of this was free. There were also pamphlets and courses on things like how to save a document, how to browse the internet, and how to use social media (presumably for the elderly).

In fact while I was walking around the Inspiration Lab I saw someone giving a talk to about 12 people on ISBN numbers and how to publish your own book, and someone recording their narration of a book…

And this is something that is explicitly encouraged and facilitated by the library:

Since coming home and reading their Annual Report I quickly realised that the VPL is not the norm, either in Canada or in the OECD countries, and certainly not in South Africa. The Vancouver Public Library was ranked the best library in the world in one study. Now obviously these rankings (like all rankings) are a little dodgy, but the point is that this is one of the top libraries in the world.

My thoughts about VPL have been sloshing around in my brain for a week now and I’ve started realising a number of things about myself and public versus private goods. Growing up I think we did visit the public library a few times but it wasn’t anything spectacular or interesting. I never developed a love of public libraries or fully appreciated the role they could play in providing a social commons where books, information and knowledge were the principal means of engagement and interaction. Rather they were low-budget cranky places with old books and old people. Instead I developed a love of book-shops and book ownership. I think this was because walking around a good book shop felt welcoming and interesting; it has new books, has displays, has events (book launches, readings, discussions), it doesn’t feel grimy. But this is only because I can afford to buy the books that I like. And so here I start to see in my own life one small example of the way that the South African cogs work to perpetuate an unequal system. I don’t use a public library because they are of low quality, I buy books instead. So I never see the value of funding and using a great public library (at least until now). So here we are with thousands of wealthy people with small private libraries essentially each creating their own space that could otherwise be collectively provided by a great public library (and with public funds), which could then also be used by everyone.

I’m sure you can see that it’s not difficult to find the parallels between this and the private provision of healthcare, schooling, legal services, recreational facilities etc as compared to the public provision of these services. So it feels like we’re in a low-level equilibrium where the rich in SA can afford to fund for themselves whatever they need without any recourse to their tax money, and the poor are forced to accept whatever the government provides. This explains why many tax-payers (at least the South African tax-payers I know) see their tax as a kind of fee where you pay it with little expectation of return or service.

It costs a lot of money to fund and operate the 22 libraries that make up the Vancouver Public Library system, R527 million to be exact. Yet 94% of Vancouver residents support the use of tax dollars to fund the VPL.

If I had to say, I do not think that we can simply say “the first step is that the libraries that we do have need to better serve the communities within which they are situated.” while of course that is true, the apartheid legacy means that there are very few well-resourced libraries in the poorest areas (notably townships). I think it is an open question, and one that’s worth discussing, whether a functioning public library system that has the expertise and resources to support local residents (and especially local schools) is worth the considerable resources it would take to create such a system. The case needs to be made that (and in my view, is yet to be made) that it is possible to create such a library given our capacity and resource constraints. And secondly that it is a better use of resources than additional money on housing, child-support grants, teacher development etc.

I’m interested to hear your thoughts Equal Education, Nal’ibali, Bookery, Fundza, Bookdash and everyone in this space. Should we be funnelling millions of rands into creating functional public libraries in low-income high-density locations like Khayalitsha? Why aren’t we? Do we know how to do it? Who should lead the way?

Posted in Education, reading, Uncategorized

[Image: Norman Akcroyd]

[This article first appeared in the Mail & Guardian on the 4th of March 2016]

Afrikaans universities perpetuate racial divisions – Nic Spaull & Debra Shepherd

In the last 2 weeks we have seen a number of protests erupt at former Afrikaans-only universities, specifically at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State. The reasons for the protests were numerous and included workers’ wages, accommodation, fees and the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. At Stellenbosch University, a court case between AfriForum and the University was settled out of court last month and seemed to involve a reversal from the position of making English the primary medium of instruction at the University and instead giving English and Afrikaans equal status. For too long the issue of language in education has been dominated by ideological viewpoints that have little appreciation for, or understanding of, the empirical reality in South Africa. Of course language is inherently political – dealing as it does with issues of power, culture and identity – but those promoting or opposing a particular view need to show how those views square up with the linguistic, historical and socioeconomic context that we find ourselves in. Our aim here is to put some empirical evidence on the table so that we can move away from the anecdotes and ideologies that are currently driving policy and public-perception.

For over 50 years the apartheid government nurtured and resourced White-only schools and universities – both English and Afrikaans – while systematically under-resourcing institutions serving Black students. At the height of apartheid, the government allocated the same amount of resources to one White student at school as it did to 10 Black students at school. Even at the end of apartheid the average White child was receiving three and a half times as many resources from the government as the average Black child in one of the homelands. This legacy lives on in the post-apartheid period with ‘ex-Model-C’ schools continuing to be well-resourced as a result of the inertia of institutional functionality and the on-going investment by parents (of all races) that can afford fees, bequests and donations. The same can be said for former-White-only universities.

At universities the three major barriers preventing Black students accessing high-quality institutions are fees, language and weak academic results (from attending dysfunctional schools). The evidence of financial exclusion and financial inaccessibility is now well known. A research note published by our colleagues earlier this year showed that the cost of a BA degree at Stellenbosch had increased 30% between 2006 and 2015 and now requires 44% of average adult income. However there is far less evidence on the table about how many students are excluded from Stellenbosch because of language.

Of those students who qualified with a bachelor’s pass in matric 2014, every single student in the country took either English Home Language or English Second Language. In contrast, 61% of matrics who qualified with a bachelor’s pass did not take any Afrikaans subjects, either as a Home Language or a Second Language. If one looks at Black African students only, then 86% took no Afrikaans at all. It is reasonable to assume that 86% of Black African students who qualify to go to university understand no Afrikaans at all. How then are these students meant to understand some of their university subjects in Afrikaans if they are accepted at our university?