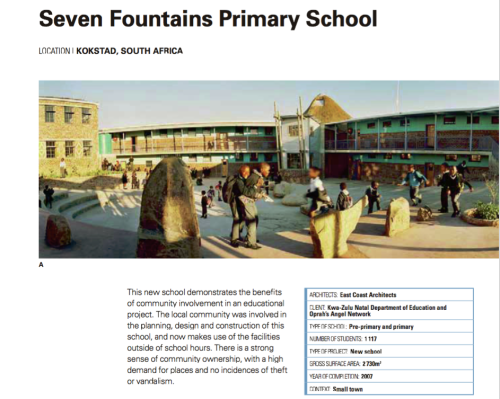

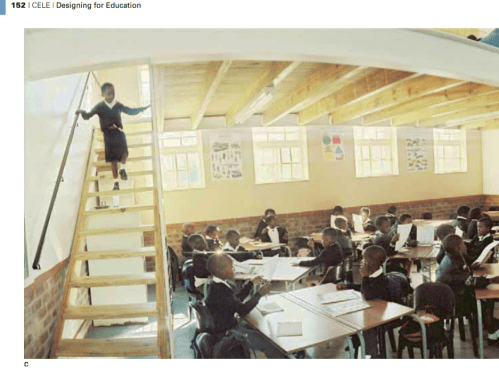

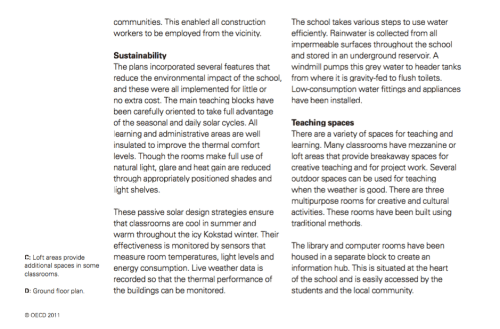

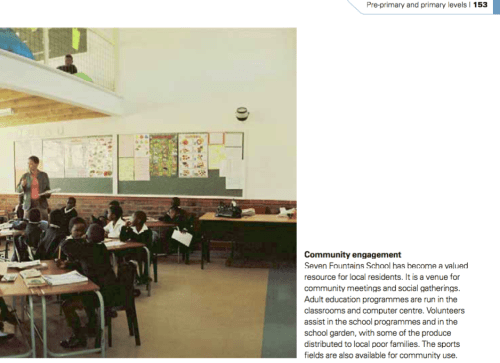

The above was one of the case studies featured in”Designing for Education” – a publication by the OECD (2011). More information about the design of this school can be found here and here.

The above was one of the case studies featured in”Designing for Education” – a publication by the OECD (2011). More information about the design of this school can be found here and here.

Posted in Architecture, Uncategorized

What makes a school really great? Those first impressions that count” – Dr Gabi Wills

Curriculum coverage? Teacher motivation? Print-rich environments? Learning goals and targets? These are a few of the things that I see as important as I have looked through mounds of literature on what makes an effective school. Together with a team of education experts we are preparing to engage in research in schools in South Africa in township and rural areas that exceed despite the odds. In preparation we are having to think hard and fast about questionnaires to capture what it is that separates these schools from the rest. Most of the time this can be a surprisingly difficult task. In post-Apartheid South Africa there have been numerous studies on schools where data is captured on indicators of school functionality. Using our fanciest modelling, we then try and see which of the many indicators of observed factors explain why certain schools do better than others. But most of the time we simply can’t explain the variation in learner performance that we observe across schools, particularly in the majority of poorer schools in the system. I am however starting to wonder if we simply have not measured effectively the things that really count.

As academics we tend to limit ourselves to our peer-reviewed readings, to our computer screens and the occasional conference. But we miss too many opportunities for the ‘aha’ moment when it all comes together. Increased burdens of work limit time to experiment and explore. Well at least for me. After feeling unusually disimpassioned and just wearied by just too much information, today I did something different but obvious. Rather than running off to the office and opening my computer, I started my day in the reception of a great preparatory school in Durban. I sat and observed. I started reading the display books on the reception table, observed the honour boards proudly displayed, watched teachers coming in and out and hearing in the background the sound of children vocalising their prose for the next drama production. After 60 minutes of this, and particularly reading an inspiring 2010 prize-giving speech of the headmaster in one of the coffee table books, things were becoming clearer. Before I even got to the classroom, I realised that great schools do this:

But you are probably wondering why these two features (past history, past achievement) matters for the now? The importance of this extends beyond school pride, it legitimises the worth of the institution beyond one individual. Great people create great institutions with a reason for existence beyond their founders. Moving on, great schools….

These are just four observations before I have even spoken to a single person. Moving on to meeting two principals in the school…

After just 2 hours, I think I have got clearer what my next questionnaire needs to be about and probably saved myself two day of agonising thinking. For all our studies after just bumbling along as a regular person I come that much closer to realising what matters, what separates out the average school from the great. I suspect I have just observed what every interested parent or teacher has known all along.

//

One of Gabi’s recent Working Papers on principal leadership changes in South Africa is available here.

Posted in Guest blog, Uncategorized

Fieldworkers required: Research on Socio-Economic Policy (ReSEP), based in the Economics Department at Stellenbosch University, has embarked on a research project focussing on exceptional township and rural primary schools in three provinces in South Africa. ReSEP plans to recruit 9 experienced fieldworkers to assist them with school-based research.

Job description: Fieldworkers

Periods of work: Early October 2016 with an option to renew for forthcoming fieldwork

Overall period of fieldwork: Early October 2016, February/March 2017, September/October 2017

Daily rate for fieldwork: R800 per day with R100 per day subsistence allowance

Daily rate for training: R450 per day

Description of the project: The main aim of the research is to better understand why some schools perform better than others specifically in township and rural areas. We will develop a new survey instrument that captures the actual practices and behaviours of teachers and principals in challenging contexts.

This will be done where each exceptional school is paired with a nearby ‘typical’ school, i.e. one with similar geographical and socioeconomic characteristics.

The study will be conducted in various phases from May 2016 to September 2018 in 60 schools across the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces. This advert is based on fieldwork for the first phase, piloting the various research instruments in three schools per province, this may however be extended to the subsequent data collection phases (February and October 2017) based on fieldworker performance and availability.

Fieldworkers will be required to

Minimum requirements: 1) A bachelor’s degree (although in exceptional cases 3 year diploma’s also considered) 2) Fluency in reading and writing in English as well as one of the three following languages: Sepedi, isiZulu or IsiXhosa

Preference will be given to individuals:

Qualities:

Ideal candidates should possess the following qualities:

Required time commitments:

Application:

12 shortlisted candidates will be required to attend training at a central location where 9 fieldworkers (3 per province) will be chosen from the most suitable candidates identified. All shortlisted candidates will be compensated the daily rate of R450 for the duration of the training.

If you are interested in applying for the position please send to mschreve@sun.ac.za by Mon. 8 August 2016

i) Your CV. Including two references.

ii) A short written piece (500 word limit) on what characteristics/features in your opinion distinguish a school as being better than others. The piece must be written in English and in one of the three following languages: Sepedi, isiZulu or IsiXhosa.

iii) A covering letter. In your covering letter please explain why you think you would be a good match for this position. In the subject line please include: “Application: ESRC fieldworker.”

The University reserves the right to investigate qualifications and conduct background checks on all candidates. Should no feedback be received from the University within four weeks of the closing date, kindly accept that your application did not succeed.

Posted in Uncategorized

Some things I’ve been reading:

New Research:

This article reports on a two-year evaluation of the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS), an innovative system-wide reform intervention designed to improve learning outcomes in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Using data from universal testing of all learners in 2008 on a provincial systemic evaluation, as well as data from the 2011, 2012 and 2013 Annual National Assessment tests, this article investigates whether or not the GPLMS improves the numeracy skills of learners in early-grade mathematics in underperforming schools. Using as identification strategy, the natural experiment that resulted from a miscalculation of the provincial systemic evaluation test scores in 2008, which had been used to assign schools to the GPLMS intervention, the study shows that the GPLMS intervention is positively associated with improvements in early-grade mathematics performance of schools in the neighbourhood around the assignment threshold. The findings of the study contribute to the growing body of knowledge that shows the effectiveness of combining lesson plans, learner resources, and quality teacher capacity building.

Posted in Links I liked..., Uncategorized

I haven’t been blogging for a while for a couple of reasons. I’ve moved to the OECD in Paris for the TJA Fellowship and will be here until the end of August. I’m working on PISA data in middle-income countries and finding some really interesting results – working paper(s) should be done by the end of the year and I’ll be back in South Africa mid-September.

In the last few months it feels like the world became a much more interesting and scary place than it was this time last year. Apart from things like Brexit and Trump, there’ve been terrorist attacks around the world showing how vulnerable big cities are (even in wealthy countries) to very small groups of people with bombs and guns. In the last two days there has been a terrorist attack in Nice (France) and yesterday a failed coup in Turkey. So I think I’ve been running low on good news for a while. Then I was reminded of Sci-Hub, which is kind of the Naptster/PirateBay of academic publishing. If you know the DOI (document object identifier) or the journal name you can usually find it on Sci-Hub. It was founded by a 22 year-old graduate student from Kazakhstan, Alexandra Elbakyan. The site provides up-to-date access to 50 million articles. In February 2016 alone there were 6 million downloads. Providing access to the world’s academic knowledge to anyone with an internet connection is absolutely amazing. It’s also something that one of the Internet’s geniuses, Aaron Swartz, seemed to be planning before his untimely death (suicide). Millions of people (myself included) have access to online journal articles, primarily through institutional access arrangements (typically universities). Having such a distributed network of people, all of whom have access means that something like this was bound to happen and is impossible to prevent. Much like downloading pirated movies or music which are here to stay. This is creative disruption in its purest form.

I think Alexandra is a hero and that Sci-Hub is here to stay. It’s bull-shit to argue that the peer-review process depends on 37% profit margins (Elsevier) or heavily gated elite journals. The logic that we must conduct research using tax-payers money, then submit and review the articles for free but that we must pay to get access to those articles is totally antiquated and perverse. This also explains why countries (such as the US) and donors (such as the Gates Foundation) are requiring that research that they fund be made available online within a year of completion.

Onward and upward…

Posted in Higher education, Uncategorized

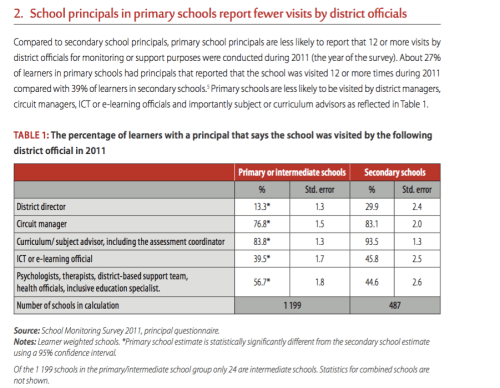

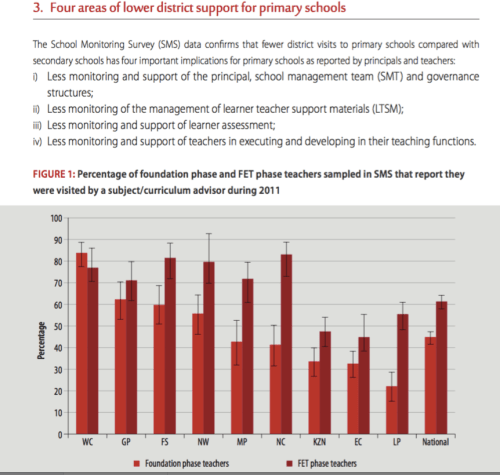

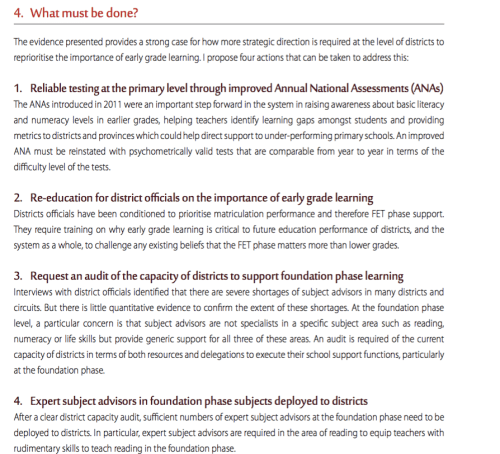

In her latest policy brief, my friend and colleague Dr Gabi Wills discusses the overprioritisation of matric/high-schools and the underprioritisation of Foundation Phase (Gr1-3) and primary schools. The full policy brief is here. She finds that high school principals are significantly more likely to have been visited by a dsitrict official than a primary school principal, leading to lower monitoring and support at this critical phase. The need to prioritise the Foundation Phase and reading specifically was the main conclusion from two major research projects that we have just finished (see here). Until we realise that we will win or lose the battle of improved educational outcomes for the poor in the primary school, and specifically in Grades 1-3, then we are doomed to go around this mountain one more time!

I include some excerpts from the policy brief below:

Posted in Uncategorized

I have now moved to Paris to work at the OECD for my TJA Fellowship on PISA data in developing countries. This is essentially an extension of my work on SACMEQ/PASEC and DHS, trying to combine surveys of achievement and attainment to get a composite measure of education system performance. While I’m away I won’t be commenting as regularly on SA education issues as I usually do. And I will probably shift my focus to other developing countries which is the topic of my research at the OECD. I have already found a number of fascinating things about some PISA countries which I don’t think are widely known or fully appprecaited. There is more than enough included in my previous blog post (11 policy briefs, two synthesis reports and a 200+-page special issue of the SAJCE), not to mention the Volmink Report, for the media and policy-makers to focus on for the next 2 years, let alone 3 months. Keeping up with the nitty-gritty doesn’t make much sense when the underlying issues are not being addressed or taken seriously.

To be honest I’m quite glad to be taking a break from South African education and working on PISA and learning about PISA-for-Development. Clear outcomes, a competent team, and political will. That’ll be nice 🙂

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

For the last two years we at RESEP have been working on two major education projects: The “Binding Constraints” project (Presidency/EU) and the “Getting Reading Right” project (Zenex Foundation). We launched the two reports on Tuesday last week (my presentation is here). Included below are the two project synthesis reports, a detailed outline on a prospective course (which needs a funder) on “Teaching Reading (& Writing) in the Foundation Phase” and 11 policy briefs. I’ve also included the “Roadmap for Reading” which provides a detailed outline of the practical steps that the Minister of Education could take if she wanted to prioritise reading in the Foundation Phase.

All of the above are also available on the RESEP website here. The 2015 special issue of the South African Journal of Childhood Education (SAJCE) where most of the research was published is available here (ungated) for those who would like to read the full journal articles.

The presentations from the event are available here:

(I would especially encourage everyone to read through Servaas’ and Gabi’s presentations, they were exceptional!)

There is obviously a lot to be said about these two projects, some of the new research points to very tangible, actionable steps to improve the education system, decrease inequality in outcomes and arguably create a fairer and more efficient education system. Yet it is not at all clear that any of these suggestions will be followed. It was unfortunate that neither the Director General nor the Minister were able to make the report launch. I am aware that both have very busy schedules and that a lot has been happening in education in the last few months. I hope that Servaas will have an opportunity to present this research to them in the coming months. I have also been underwhelmed by the online coverage of the research.

I deliberately do not want to write about the research now since I am currently a little jaded and frustrated about the education research, funding and policy space (perhaps you can tell!). When there are clear, unambiguous and actionable steps that could be taken to improve the education system and they are not taken, this is frustrating. When funders choose to channel millions (billions?) of rands in fruitless directions toward unevaluated projects, it is frustrating. When clear priorities and needs are ignored by national government and local funders (like developing a high-quality course to teach foundation phase teachers to teach reading!), it is frustrating. And perhaps most frustrating of all is the large number of people in provincial and national government that are unable to do the jobs that they have been appointed to do. While there are a number of dedicated and competent public servants and politicians in education, the way that our system is set up means that they have to rely on people who cannot do what they are being asked to do. Those people need to be trained quickly or performance-managed out of the system. That will take courage, strategic leadership and a clear understanding that the status quo is preventing poor children from quality education. Indeed “Weak institutional functionality” or “Insufficient State Capacity” was one of our four binding constraints. Go figure.

Posted in Education, Uncategorized

The Ministerial Task Team Report into the sale of posts – colloquially referred to as the Jobs-for-Cash report has finally be released by the DBE. Full report HERE. The report is far-reaching, frank and damning. We all owe a huge thanks to Professor Volmink and his team for their investigation and this much needed report. When corruption is so systemic, as it is in SA education, to write a report like this without fear or favour is the mark of a deep conviction that something has to change.

I have taken out a few excerpts for those who don’t have time to read the whole (285-page report:

Some media reports are starting to emerge in Times Live and Citizen but it will be interesting once the journalists and commentators get their teeth into the detailed report.

Posted in Uncategorized

This was first published in the Mail & Guardian on the 13th of May 2016. The PDF of the article is also available as text below:

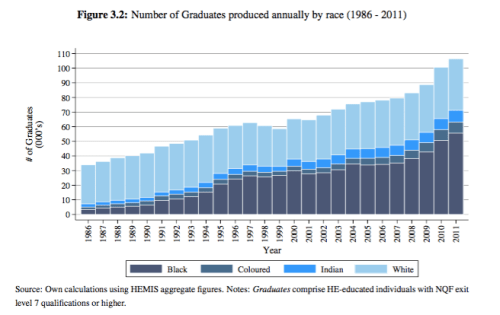

Black graduates have doubled in last 10 years – Dr Nic Spaull

As someone who has written quite extensively about the failings of our education system, I was unusually surprised by the quotes emerging in the media coverage of a recent Stats SA report and even more so by the Statistician General Pali Lehohla’s comments last week. Following publication of the report, titled “The Social Profile of Youth”, the Business Day was quick to inform us that apparently black youth were “less educated now than 20 years ago.” The Daily Maverick ran a similar headline: “Stats SA claims black youth are less skilled than their parents”, with equally alarmist coverage in Times Live, ENCA, SABC etc. Unfortunately StatsSA did not denounce the media’s claims. The story seems to have grown legs, with former president Thabo Mbeki calling it a “national emergency” and the Shadow Minister of Basic Education speaking of “the collapse of education in poor communities.”

Of course none of this is true. As we shall see, Black youth have higher levels of educational attainment today than at any other point in South Africa’s history. There are more Black matrics, more black high level passes in mathematics and science, and many more Black university graduates. (Note that this is both as a proportion of the Black population and in absolute terms). In this article I will focus on black university graduates since everyone agrees that there have been large increases in black youth passing matric and achieving bachelor’s passes.

If we cut to the chase the confusion all centres on one strange graph (Figure 4.2) appearing on page 64 of the 2015 Stats SA report “Census 2011: A profile of education enrolment, attainment and progression in South Africa” and the misinterpretation of what that graph apparently shows. That graph shows that the proportion of black and coloured youth that graduate with a bachelor’s degree “after completing matric” has been declining for 20 years, while for whites and Indians it has been increasing. This is very strange and does not seem to agree with other, perhaps more reliable data sources. Unlike when trying to measure things like the unemployment rate or wages (where you have to turn to household survey data or the Census), when counting the number of university degrees awarded it’s a little easier. We can look at surveys, but we can also just look at the Higher Education Management Information System (Hemis) the record-keeping system stating who has been granted what degree and when. All degrees that are granted must be recorded on this database. So what does Hemis tell us about the number of black youth actually getting degrees over the last 20 years?

Fortuitously, this exact question was addressed in a Stellenbosch Economic Working Paper (08/16) published last week by my colleague Dr Hendrik van Broekhuizen. In that paper he shows that “while the number of White graduates produced annually has increased only moderately from about 27 500 to just over 35 000 in the past 25 years, the number of Black graduates produced has increased more than 16-fold from about 3 400 in 1986 to more than 63 000 in 2012.” For this article I was particularly interested in degrees rather than diplomas or certificates) and he kindly provided the figures for degrees only by race (see figure below). The changes have been equally dramatic. Between 1994 and 2014 the number of black graduates with degrees being produced each year has more than quadrupled, from about 11,339 (in 1994) to 20,513 (in 2004) to 48,686 graduates (in 2014). Even if one only focuses on the recent period between 2004 and 2014 Black graduates increased by about 137% (compared to 9% for whites), while the black population grew by about 16% over the same period.

This might lead us to yet another famous South African myth; that graduate unemployment is high (it isn’t) or increasing (it’s not). Again, rigorous research by Dr Van Broekhuizen and Professor Servaas van der Berg convincingly debunks this hoax. They conclude their research report as follows: “The frequently reported ‘crisis in graduate unemployment’ in South Africa is a fallacy based on questionable research. Not only is graduate unemployment low at less than 6%, but it also compares well with rates in developed countries. The large expansion of black graduate numbers has not significantly exacerbated unemployment amongst graduates….Black graduates are, however, still more likely to be unemployed than white graduates.” (Note: in 2015 black graduate unemployment was about 9% compared to 3% for whites.) [Their extended article is here]

Another colleague of mine, Dr Stephen Taylor in his response to the Statistician General (Business Day, 29 April) has shown why Stats SA’s Figure 4.2 is so misleading (essentially the increase in black matrics was larger than the increase in black graduates, but both increased substantially). Unfortunately the SG has simply lashed out at Dr Taylor referring to his critique as “technically incomprehensible and policy irrelevant” (Business Day, 5 May). To avoid a similar riposte let me be clear: Black graduates have more than doubled in the last ten years. The black population hasn’t. Therefore, black youth are more likely to get degrees than 10 years ago. I think this is both technically comprehensible and policy relevant.

The argument that “black youth are regressing educationally” feeds a dangerous narrative that is not supported by any education data in South Africa. Not improving fast enough, yes. Regressing, no. Black youth have higher educational attainment now than at any point in South Africa’s history. This does not change my firmly held view that our education system is in crisis and that we need meaningful reform, that goes without saying. The egregious levels of educational inequality between working class and middle-class families, and between whites and blacks should cause alarm. And yes, our youth unemployment problem is monumental and unsustainable; there is widespread and legitimate research to show that. But spreading fallacious rumours and causing doubt where there is none, helps no one. Together with a number of colleagues and officials I would ask the Statistician General to please clarify his comments on black graduates and set the record straight.

//

Dr Nic Spaull is a Research Fellow at the University of Johannesburg, the University of Stellenbosch and the OECD.

Workings for graphs (thanks Hendrik van Broekhuizen!)

| Year | Black | Coloured | Asian | White |

| Y1986 | 2957 | 1131 | 1532 | 17601 |

| Y1987 | 3153 | 1280 | 1692 | 19064 |

| Y1988 | 3546 | 1349 | 1771 | 20494 |

| Y1989 | 4043 | 1760 | 1930 | 21613 |

| Y1990 | 4862 | 1958 | 1975 | 22747 |

| Y1991 | 7115 | 2230 | 2170 | 23800 |

| Y1992 | 8130 | 2270 | 2363 | 24901 |

| Y1993 | 8661 | 2392 | 2621 | 24571 |

| Y1994 | 11339 | 2127 | 3023 | 25538 |

| Y1995 | 13123 | 1833 | 2506 | 16885 |

| Y1996 | 15781 | 1785 | 2479 | 16363 |

| Y1997 | 17367 | 1869 | 2713 | 16385 |

| Y1998 | 17181 | 1949 | 2796 | 15650 |

| Y1999 | 19093 | 1785 | 2175 | 15410 |

| Y2000 | 20379 | 1909 | 3193 | 15896 |

| Y2001 | 17017 | 1913 | 3430 | 16017 |

| Y2002 | 16222 | 2075 | 3712 | 17094 |

| Y2003 | 17234 | 2322 | 3776 | 17948 |

| Y2004 | 20513 | 2640 | 4307 | 18757 |

| Y2005 | 21052 | 2916 | 4505 | 19860 |

| Y2006 | 22508 | 3097 | 4805 | 20732 |

| Y2007 | 23356 | 3480 | 4840 | 20522 |

| Y2008 | 25373 | 3677 | 4984 | 20482 |

| Y2009 | 27869 | 3866 | 4774 | 20555 |

| Y2010 | 31453 | 4366 | 4690 | 20456 |

| Y2011 | 34209 | 4456 | 5109 | 20248 |

| Y2012 | 40001 | 4778 | 5089 | 20303 |

| Y2013 | 45948 | 5291 | 5748 | 21548 |

| Y2014 | 48686 | 5622 | 5529 | 20510 |

*These include the following: General Academic Bachelor’s Degree; Professional First Bachelor’s Degree; Baccalaureus Technologiae Degree; Professional First Bachelor’s Degree; First National Diploma (3 years); First National Diploma (4 years)

| Figures refer to the number of HE awards and will thus be at least as large as the number of graduates produced in each year. Includes only undergraduate degrees. (Thus excludes all UG diplomas, and certificates |

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, Uncategorized

[Guest post – Stephen Taylor]

The Statistician General (SG) recently responded to my letter to the Business Day. A full version of what I have written is available here. I would simply reiterate what I wrote initially. In brief:

Numerous newspapers and media outlets were running with headlines such as “Black youth less educated now than 20 years ago” (Business Day) and “Stats SA claims black youth are less skilled than their parents” (Daily Maverick). The articles were referencing a recent Stats SA report as well as comments made by the SG.

My position is simple: These claims are factually incorrect and Stats SA reports and data do not actually say this. Note that I did not “adjudge a mistake” in the actual Stats SA report. I do not know exactly what the SG said at the release, which may have lead the media to run with the headlines they did, but I speculated about what I thought might have been causing the confusion.

The SG’s response has confirmed that I was right about what had caused the confusion. He had in mind a very specific “progression ratio” – the ratio of degree graduates to matriculants. This ratio may have been decreasing for black and coloured youth, but this is simply because the increase in degree graduates has not kept pace with the increase in matriculants. Importantly, both the likelihood of achieving a matric and the likelihood of achieving a degree have been fast increasing, especially for black youth. This means it cannot possibly be true that black and coloured youth are worse off educationally than their parents, which is the message the media were propagating. None of the media reports said anything about this “progression ratio” which the SG has now referred to. Instead the media were reporting that lower proportions of the entire black and coloured population were attaining a degree. And that isn’t true.

According to Higher Education data, the number of black degree graduates per year has increased more than four-fold from 11 339 in 1994 all the way to 48 686 in 2014.[Note: New SU Working Paper published by Hendrik van Broekhuizen last week on this topic]. This is much faster than population growth. For white youth, this number has essentially remained flat at roughly 20 000 graduates per year. Of course there is still a lot of inequality – these numbers mean whites are still about 6 times more likely to attain a degree than black youth.

This “progression ratio” may have some analytic value, as the SG points out. For example, it may reflect a greater policy prioritisation of secondary education relative to higher education. But this indicator must be clearly explained and it also has its limitations. I cannot imagine anyone celebrating improved educational outcomes if the numbers of black and coloured youth attaining a degree had gone down, while the numbers attaining a matric had gone down even faster, leading to an increase in the degree-to-matric progression ratio!

I know progress hasn’t been as fast as we need. But it is far from the truth to suggest educational outcomes have regressed.

Posted in Uncategorized

On the topic of the change in the number of black African graduates over the last twenty years (and the recent media hype) this study by my colleague and friend Dr Hendrik van Broekhuizen is all that needs to be said:

“In addition to the expansion of South Africa’s yearly graduate outputs, the nature of the policy changes which have affected the HE system over the past 25 years means that the demographic composition of South Africa’s stock of graduates has also changed radically over time. This is clearly evident when looking at changes in the racial composition of the graduates produced by the HE system each year. Figure 3.2 reveals that, while the number of White graduates produced annually has increased only moderately from about 27 500 to just over 35 000 in the past 25 years, the number of Black graduates produced has increased more than 16-fold from about 3 400 in 1986 to more than 55 600 in 2011. The implications of the racial differences in graduate output growth are simple: while the HE system produced 7.9 White graduates for each Black graduate in 1986, by 2011 it produced 1.6 Black graduates for every single White graduate. Figure 3.3 offers a similarly poignant illustration of the extent of change in the racial composition of South Africa’s stock of graduates by showing the respective racial shares of the total number of graduates produced in each year since 1986″ (p13).

From his 2013 Economic Society of South Africa paper.

Posted in Guest blog, Higher education, Uncategorized

Hi education folk

We’ve recently been awarded a grant by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and DFID to do research on exceptional township and rural primary schools in three provinces – Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo. I will be leading the project together with a great team of co-investigators and researchers: Ursula Hoadley (UCT), Jaamia Galant (UCT), Nick Taylor (JET), Servaas van der Berg (ReSEP), Gabi Wills (ReSEP) and Linda Zuze (HSRC).

Given that we will be using a matched-pair approach, the aim of the project is to to firstly identify at least 10 high-performing township/rural schools in each of the three provinces and then match those schools to ‘typical’ neighbouring schools (thus 60 schools in total). The project will run for 2.5 years (beginning June 2016) and will involve in-depth qualitative research, administering and analysing assessments, creating new school-leadership and management instruments and analysing the data emerging from the project.

At the moment we are looking for a part time (50%) project administrator to help us with the administration relating to the project. The full job-advert can be found here. I include a short extract:

The ideal candidate should be an efficient and organised person with some experience in managing the administrative side of academic projects. They should be friendly and able to communicate well, as well as plan effectively and take initiative to solve problems as they arise. They should also be able to liaise with (1) the funders – DFID/ESRC, (2) Stellenbosch University finance and administration personnel, and (3) the 5 co- investigators as well as other researchers and field-workers. The job will include following up with government officials, managing flights and accommodation, planning reporting cycles, managing time-sheets, budgets and funding claims, proof-reading and printing questionnaires etc.

They should also be friendly 🙂 Basically we’re looking for a go-to admin guru to help us with this project. If your skills and experience are such that you would also be able to help on the non-admin research side (doing research-assistant work or interviews/assessment) then we may involve you in more than an administrative role. However this would be on top of your administrative responsibilities, and in such a case the remuneration is somewhat negotiable. It is a part-time position and it’s based at Stellenbosch University (in the Economics Department) so remuneration would be in line with university salary scales (I believe it is about post-level 11, although it would be 50% of the amount stated here) and partially dependent on qualifications and/or experience.

If you’re interested in working with this great team on an exciting new project please do apply 🙂 (and if you know of anyone who may be interested please forward this on to them!)

DEADLINE FOR APPLICATIONS: 12 May 2016

Posted in Uncategorized

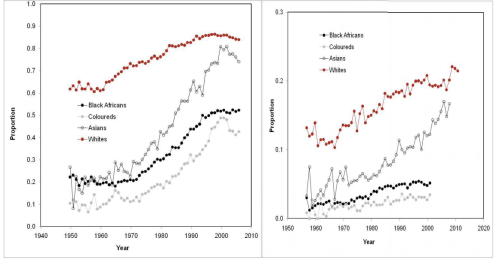

Figure 1: Proportions of the population achieving secondary education (left) and a bachelors degree (right). (Source: Stats SA (2015): CENSUS 2011: A profile of education enrolment, attainment and progression in South Africa, page 41.)

On the 18th of April the Business Day published a piece titled, “Black youth less educated now than 20 years ago.” This statement is simply wrong and unsupported by any data set. Yet the story is now gaining momentum and has been published by other news outlets, such as the Daily Maverick, reporting that “Stats SA claims black youth are less skilled than their parents.”

The article asserts that “black and coloured youths have regressed in their educational achievements” and that the proportion of black and coloured youth that complete a university degree as a share of the population has decreased. This is factually incorrect.

The article references a recent Stats SA report on the status of the youth as well as comments by the Statistician General, Pali Lohohla, as the basis for these assertions.

But in fact, the Stats SA published reports (as with all other analysis I have seen or done) indicate that the proportions of black and coloured youths who attain grade 9, grade 12, and a university degree, have all increased consistently in recent decades and are still increasing. It is thus not clear where this misconception arose.

I suspect the mistake may have arisen through a misunderstanding of a statistic which has been presented by the Statistician General recently and which appears in Stats SA’s report on educational enrolment, attainment and progression (December 2015). The statistic shows that the proportion of black and coloured youths who achieve a bachelors degree “after completing grade 12” has been declining over the last 20 to 30 years.

It needs to be understood that this statistic is the proportion of matriculants who go on to attain a degree. In other words, the denominator in this calculation is matriculants as opposed to the entire black and coloured population.

The improvement in matric attainment among black and coloured youth has been larger than the improvement in degree attainment among black and coloured youth, but – and this is the important part – there have been big improvements in both. The fact that the increase in degree completion has been slower than the increase in matric completion is not at all an indication that youth are worse off now than 20 years ago.

So the ‘bad’ news is that degree completion, although it has increased, has not kept pace with the fast increase in the attainment of matric amongst black and coloured youths. But this certainly does not mean that educational outcomes are worse than 20 years ago.

So what do the numbers actually say? The Stats SA report issued in December shows that the proportion of black people completing matric has been consistently increasing from about 20% to about 50% over the last 50 years. That report also indicates that the proportion of black people completing a degree has increased from about 2% to about 4% over the same period.

Whether you read official Stats SA reports or do your own calculations on the various Stats SA datasets – I have analysed Census data from 1996, 2001 and 2011 as well as General Household Survey data from 2002 to 2014 – it is clear that both matric attainment and degree attainment has been increasing amongst the black and coloured population.

It is also useful to consider the Department of Basic Education’s matric statistics from recent years. In 1990, there were 191 000 matric passes. By 2015 this number had more than doubled to 465 863. This increase has been driven mainly by growing numbers of black youth passing – and this growth has easily outstripped population growth, which has been about 1% a year. Even since 2008, the number of black matric passes has increased from about 250 000 to over 350 000. And the number of black people achieving a bachelors pass in matric has increased from about 60 000 to about 120 000 since 2008.

I am by no means suggesting that everything is fine in our education system. Despite the progress, there are still too many youths who do not get to grade 12, the main reason being that educational foundations laid in earlier grades have been inadequate. And completion rates at our higher education institutions should worry us. But there have been improvements in both of these areas relative to 20 years ago.

Although improved access at lower levels of education (primary and secondary school completion) has been faster than access at higher levels, paradoxically the solutions must focus on the early grades if sustainable progress is to be made.

The most alarming education statistics to me are the low proportions of children achieving basic literacy and numeracy in the early grades. International assessments of education quality point to serious deficiencies in this area, even compared to some other countries in the region. If children are not learning to read in the early grades, they will not be able to make it to higher education.

But even in the area of learning quality, the evidence points to improvement. The Trends in International Mathematics and Science study (TIMSS) showed substantial improvements in mathematics and science achievement at the grade 9 level between 2002 and 2011. However, this improvement is off a very low base.

Educational outcomes in South Africa remain far too low, especially amongst youths from poor communities. But claims that education was better under apartheid or that outcomes have deteriorated over the last 20 years are alarmist and have no basis in reality.

—

Dr Stephen Taylor is a researcher in the South African Department of Basic Education. His work includes impact evaluation of education interventions, measuring educational performance and equity in educational outcomes. In 2010 he completed a PhD in economics at the University of Stellenbosch, analysing educational outcomes of poor South African children.

(This article first appeared in the Business Day on Friday the 29th of April 2016)

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, Uncategorized

I’m currently involved in a number of research projects that look specifically at reading in the Foundation Phase in South Africa. In my view this is the cause of (and solution to) so many of the problems we see in our education system.

I thought it would be a good idea to get some of the SA reading researchers in the same room to talk about the work they’re currently doing and talk about the way forward. So we’ve organized a half-day workshop for the 28th of April (8:30am-2:30pm). It will be an informal seminar of researchers and should be relatively small (<40 people) to make sure we have time to interact.

Prof Elbie Henning at UJ has kindly offered to host the workshop at UJ (as an aside I am now a part-time research fellow at her SARChI Chair). See the programme below. There are a number of exciting presentations, perhaps most exciting is early feedback from Stephen Taylor et al’s RCT in the North West!

The good news is that we have additional space for 5 or 6 additional participants who would like to attend. So if you’re involved in reading research, teaching reading teachers or policy-making in the Foundation Phase and would like to come on the 28th please send me an email (nicholasspaull[at]gmail.com) with the title “Reading in FP Workshop.” Please also include a paragraph about who you are and why you’d like to attend.

| Time | Presenters |

| 08:30 – 09:00 | Morning tea and coffee |

| 09:00 – 09:20 | Nic Spaull, University of Johannesburg/OECD

Reading in the Foundation Phase – introduction, welcome and overview |

| 09:25 – 09:45 | TBD |

| 09:50 – 10:10 | Deborah Mampuru, University of South Africa

Reflections on the development of the African language DBE Workbook series |

| 10:15 – 10:35 | Elizabeth Pretorius, University of South Africa

Oral Reading Fluency and other components of ESL reading: What we know and what we still need to discover |

| 10:40 – 11:00 | Stephen Taylor, Department of Basic Education

Preliminary results of a Randomized Control Trial assessing an early grade reading intervention in the North West |

| 11:00 – 11:20 |

Tea and coffee break |

| 11:25 – 11:50 | Elizabeth Henning, University of Johannesburg

Vision for the new NRF SARChI Chair in Integrated Studies of Learning Language, Mathematics and Science in the Primary School |

| 11:55 – 12:20

|

Brahm Fleisch, Wits University

Reflections on large-scale interventions: Overview of ongoing interventions and discussion of the Triple Cocktail |

| 12:20 – 13:20

|

Carol Nuga Deliwe, Department of Basic Education & Nic Spaull, University of Johannesburg/OECD

Facilitated discussion with everyone on prioritising reading in the DBE – moving from rhetoric to implementation |

| 13:30 – 14:30 |

Lunch |

Posted in Uncategorized

Research

Minding the gap?’ A national foundation phase teacher supply and demand analysis: 2012-2020 – Green, Adendorf & Mathebula (2015)

Abstract: This paper explores the extent to which foundation phase teacher supply meets demand in South Africa, against a backdrop of considerable change in an education system endeavouring to fulfil the needs of a 21st century society while still battling with significant inequalities in the distribution of skills. The primary purpose of the paper is to use recently sourced teacher education data from a range of national databases to determine to what extent state-led interventions are assisting to meet the foundation phase teacher supply and demand challenge. The data, as well as the more qualitative aspects of their context, are analysed at the macro (national) level to present a more nuanced picture of foundation phase teacher supply and demand. The study attempts to move beyond simply basing an analysis of supply and demand on teacher attrition, and takes into account multiple variables that should be considered in supply and demand planning. It also goes beyond simply matching supply to demand in the most recent year for which data is available, to forecasting a future scenario which will need to be planned for. The paper concludes by suggesting steps that should be taken to ensure a better match between supply and demand.

Making Good Use of New Assessments: Interpreting and Using Scores From the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (2015) by Linda Darling-Hammond Edward Haertel James Pellegrino. Important thinking about around new assessments.

Quasi-experimental evidence on the effects of mother tongue-based education on reading skills and early labour market outcomes (Bethlehem A. Argaw∗ Leibniz University of Hanover February 23, 2016)

Abstract: Prior to the introduction of mother tongue based education in 1994, the language of instruction for most subjects in Ethiopia’s primary schools was the official language (Amharic) – the mother tongue of only one third of the population. This paper uses the variation in individual’s exposure to the policy change across birth cohorts and mother tongues to estimate the effects of language of instruction on reading skills and early labour market outcomes. The results indicate that the reading skills of birth cohorts that gained access to mother tongue-based primary education after 1994 improved significantly by about 11 percentage points. The provision of primary education in mother tongue halved the reading skills gap between Amharic and non-Amharic mother tongue users. The improved reading skills seem to translate into gains in the labour market in terms of the skill contents of jobs held and the type of payment individuals receive for their work. An increase in school enrollment and enhanced parental educational investment at home are identified as potential channels linking mother tongue instruction and an improvement in reading skills.

“Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on the Impact of an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increase on Student Performance in Indonesia” (Dee et al, 2016)

Abstract: How does a large unconditional increase in salary affect employee performance in the public sector? We present the first experimental evidence on this question to date in the context of a unique policy change in Indonesia that led to a permanent doubling of base teacher salaries. Using a large-scale randomized experiment across a representative sample of Indonesian schools that affected more than 3,000 teachers and 80,000 students, we find that the doubling of pay significantly improved teacher satisfaction with their income, reduced the incidence of teachers holding outside jobs, and reduced self-reported financial stress. Nevertheless, after two and three years, the doubling in pay led to no improvements in measures of teacher effort or student learning outcomes, suggesting that the salary increase was a transfer to teachers with no discernible impact on student outcomes. Thus, contrary to the predictions of various efficiency wage models of employee behavior (including gift-exchange, reciprocity, and reduced shirking), as well as those of a model where effort on pro-social tasks is a normal good with a positive income elasticity, we find that unconditional increases in salaries of incumbent teachers had no meaningful positive impact on student learning

Posted in Links I liked..., Uncategorized

“Treating schools to a new administration: Evidence from South Africa of the impact of better practices in the system-level administration of schools” (Gustafsson & Taylor, 2016)

Posted in Links I liked..., Uncategorized

Whenever I travel overseas I am asked the question “What is the biggest problem in South Africa?” And I typically respond, “The biggest problem or the biggest solvable problem?” In the 2000’s the biggest problem was HIV/AIDS. After hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths – the equivalent of a small genocide – the government ceded to the courts and offered life-saving ARVs to those infected with HIV and saved their lives. HIV was, and is, a solvable problem. Unfortunately the three biggest problems in South Africa today – too few jobs, too little growth, and too much inequality – are not easily solvable. And because we don’t exactly know how to ‘create’ jobs or growth, we don’t really know how to decease inequality much further.

Of course everyone has theories about how we can increase jobs, but the evidence is pretty thin. Depending on your political fancy and chosen economic guru there are various concoctions ranging from youth wage subsidies, eliminating red-tape, decreasing taxes, increasing taxes, digging holes, filling holes…you get the picture. Ask the top labour-economists in the country how to create jobs and you won’t get a straight answer (This is partly a provocation to said labour economists to tell us if there is in fact any coalesced consensus). You won’t even get consensus on the next three steps towards finding the answer; which is, incidentally, not a uniquely South African problem. So what to do? I think the best response is to keep cracking away at the problem; experimenting, evaluating, moving forward. But in the mean time we should also be allocating time, energy and resources to solvable problems; those we haven’t currently cracked but have a pretty good idea of how to do so. Epidemic HIV; distribute free ARVs. Crippling poverty; introduce the child support grant. Widespread malnutrition; provide free school meals to most children. The government should be heavily praised for all of these important initiatives.

But the problem I want to focus on here is the fact that most kids do not learn to read in lower-primary school. South Africa is unique among upper middle-income countries in that less than half of its primary school children learn to read for meaning in any language in lower primary school.

Irrespective of how tenuous or strong you believe the relationship is between education and economic growth, teaching all children to read well is a unanimously agreed upon goal in the 21st century. It is necessary for dignified living in a modern world, it is necessary for non-menial jobs, it is necessary for a functioning democracy. It also usually helps with ignorance, bigotry and a lack of empathy. In a modern context illiteracy is a disease that is eradicable, unlike unemployment or inequality. Like polio, illiteracy practically does not exist in most wealthy or even middle-income countries (defined here as basic reading). Illiteracy rates among those who have completed grade 4 are in the low single digits in wealthy countries like England (5%), the United States (2%) and Finland (1%) and less than 50% in most middle income countries such as Colombia (28%), Indonesia (34%), and Iran (24%). It’s difficult to get directly comparable estimates for the whole country but the best estimate from the recent pre-Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) surveys is about 58%. That is to say 58% of Grade 4/5 students cannot read for meaning in any language. And why is Grade 4 a critical period? The South African curriculum (like most curricula) prescribes that in the first three years of schooling children must ‘learn to read’, then from grade 4 onwards they must ‘read to learn’. The fact that almost 60% cannot learn through reading means that these children cannot really engage with the curriculum beyond grade 4. It really isn’t much more complicated than that

Reading for meaning and pleasure is, in my view, both the foundation and the pinnacle of the academic project in primary school. Receiving, interpreting, understanding, remembering, analyzing, evaluating and creating information, symbols, art, knowledge and stories encompasses pretty much all of schooling. Yet most kids in South Africa never get a firm hold on this first rung of the academic ladder. They are perpetually stumbling forward into new grades even as they fall further and further behind the curriculum.

Based on my reading of the academic literature – which may differ from others – there are three main reasons why the majority of kids don’t learn to read in lower primary school.

For me the solution is simple: we need to address these three problems: (1) decide how to teach existing and prospective teachers how to teach reading (as is done all over the world in contexts as linguistically and socioeconomically complex as our own), (2) ensure that all primary schools have a bare minimum number of books and that these are managed effectively, (3) monitor how often teachers are actually teaching and introduce meaningful training first and real consequences second for those teachers who are currently not teaching.

We may not have consensus on how to create jobs or increase growth, but there is consensus on how to teach children to read: with knowledgable teachers who have books and provide their students with enough opportunity to learn. If you want to improve matric, you need to start with reading. It’s not rocket science.

*This article first appeared in The Star on Tuesday the 29th of March

**Image from here

Posted in Education, Newspaper articles, reading, Uncategorized

Some presentations I’ve given in the last month:

Some new research…

Posted in Links I liked..., Uncategorized

This is the story of Judge Lex Mpati who went from being a petrol attendant after matric to the President of the Supreme Court of Appeal and Chancellor of Rhodes University where he studied (bartending on the side to pay for his studies). Such an inspiration that we have people like this who have gone from the very bottom to the very top.

“When you drive around Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape with Judge Lex Mpati you take in the tour of his life, starting at the old garage in Beaufort Street.Here, as a young man he worked as a petrol attendant and felt proud to be earning his own money. It was his first job after completing matric at Mary Waters High School in Grahamstown. His family had sent him here from Fort Beaufort where he grew up on a farm and attended the Catholic school in town, which stopped at Grade 8.Our tour continues, and we drive on to the motel where he once worked as a bartender. He recalls how kind the owner and manager were to him when he told them he wanted to study law. They encouraged him and allowed him to fit his bartending hours around his classes and studies.

Next is the furniture shop where he once worked as a salesman. This is the only job he has ever hated because he could not bear to see people being hoodwinked into hire purchase contracts they could not afford.Judge Mpati’s first home in Grahamstown was the two-roomed home in Victoria Road in the township of Fingo Village that he shared with his mother’s brother while schooling and later with his wife Mireille.From here we head across town to Rhodes University where he achieved his dream of studying law; a dream that started when he was arrested for illegally operating as a taxi at the railway station in 1968.

“I had just completed the night shift at the garage when I decided to make some extra money as I had the use of my grandfather’s car at the time,” he explains. “It was December and a lot of people were arriving by train, so I headed for the station and offered my taxi service. I was about to drive away with my clients when the police stopped me and charged me with pirating as a taxi.”He was given the option to pay a fine or go to court and he chose the latter. “I decided to defend myself and came up with a story about how I had gone to the station to pick up family members who didn’t arrive,” he recalls. “I explained that as I was leaving some people at the station had asked for a lift. When I told them I didn’t have enough petrol to take them home, they gave me 30c for petrol, which is how I came to be in possession of the money, which was quite a bit at the time. It cost 34c per gallon for regular and 38c for super. I felt I had done fairly well when I was found Not Guilty!” he smiles.It was not his first time in the magistrate’s court. Out of interest he had sat in on several cases when he had time off from the garage.

“I attended all sorts of cases – from early political trials of student activists from Healdtown and Lovedale to criminal cases. I would sit in the back listening to the charges being put to people and agonise over how they tried to defend themselves. Mostly they were black people and not being educated they were not able to conduct a good defence.”

He would get upset when people were sent to jail simply because they couldn’t ask the state witnesses the appropriate questions. “It was clear to me that the justice system was simply not working well and too many people were going to jail. That is what pushed me to decide to do law, I felt they needed someone who could defend them.”

Judge Mpati started his law degree at Rhodes in 1979 at the age of 30, paying for his first year with his earnings as a bartender. In his second and third year he received a scholarship, which covered his studies with some change to buy books. By this time he had met, courted and married Mireille who trained as a teacher and later as a nurse.In his third year he started working as a clerk for a legal firm in Grahamstown and stayed on after he graduated.“I mainly did criminal cases, which is precisely what I wanted to do. I was fulfilling my goal of helping people and I felt very good about it,” says Judge Mpati who was admitted as an attorney in 1985. “What made me especially proud was when people from my community would come up to me and tell me I had inspired them; that they had watched me go through university and qualify and it gave them the confidence to further their studies.”In February 1989 he joined the bar. Now an advocate he worked on his own from his chambers in Grahamstown until 1993 when he took up the post of in-house counsel at the Legal Resources Centre and immersed himself in human rights work in the Eastern Cape.“It has always been important to me to contribute to the growth of a society in which we can respect each other, not as a white person or black person, but as human beings who want to contribute to peace and upliftment in our country.”

In 1997 after he had served as an acting judge for a period of eight months, he became a judge. Two years later he was invited to the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein where he was permanently appointed in 2000. Eight years later he was appointed President.While he is based in Bloemfontein, Grahamstown is still his home and he and Mireille return whenever they can. They now live in Knowling Street, which is part of the tour, and this is where they raised their four children. Lyle (40) their eldest is a Mechanical Engineer, Dawn (38) is an attorney, Ludi (26) is in IT and Demi-Lee (21) is studying law through Unisa.Judge Mpati is now in his fifth year as the President of the Supreme Court of Appeal, which he describes it as “an extremely challenging job”.“The judges at the Supreme Court of Appeal need to be the best in the country, and we need to maintain that standard but at the same time we need to see the judiciary transform, particularly when it comes to race and gender,” he explains. “As part of the process of transforming the judiciary you appoint a combination of the best judges and judges with the best potential to reach the level at which you wish to maintain the court.”

In February this year Judge Mpati was appointed Chancellor of Rhodes University.“It feels as if my life has come full circle,” he says. “When I arrived in Grahamstown as a young boy I could never have imagined that one day I would be the Chancellor of the University I attended and of which I am so proud.”Commenting on his appointment, the Vice-Chancellor of Rhodes University Dr Saleem Badat said: “Judge Mpati personifies the values we embrace at Rhodes of rising above self, of modesty, commitment, excellence and ethical behaviour. His is an inspiring story and we are honoured to have him as our Chancellor.”

From here (via Janet Love).

Posted in Uncategorized